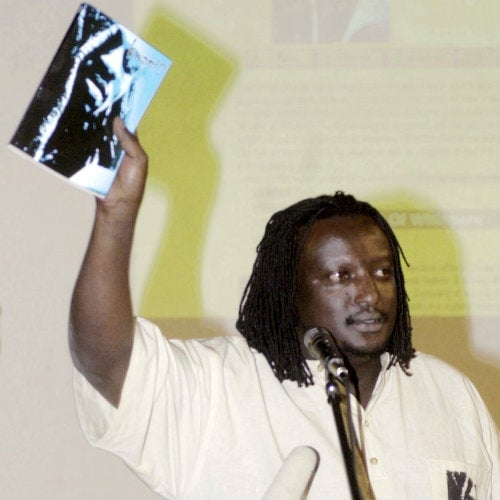

Binyavanga on how Nollywood can inspire the revival of African publishing

In the winter of 2005, Granta, the self-described British magazine of new writing, published an essay by a little known Kenyan writer named Binyavanga Wainaina. Like an instruction manual, “How to Write about Africa” began with a simple tip: “Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title.” It then asked the reader to remember that, “‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans.”

In the winter of 2005, Granta, the self-described British magazine of new writing, published an essay by a little known Kenyan writer named Binyavanga Wainaina. Like an instruction manual, “How to Write about Africa” began with a simple tip: “Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title.” It then asked the reader to remember that, “‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans.”

The piece was pure satirical gold. It articulated the frustration that many on the continent felt about the West’s writing about Africa. It ended with a visceral coup de grace: “Always end your book with Nelson Mandela saying something about rainbows or renaissances. Because you care.” Immediately, it went viral, before viral was even a thing, becoming Granta’s most forwarded article in the magazine’s history.

A lot has happened since then. The continent is no longer “hopeless.” It is a place of intriguing economic possibilities and innovative mobile technology. And Binyavanga Wainaina has moved on. “I am least interested about how Europe, the West, represents Africa. The essay I wrote, “How to Write About Africa,” was written in 20 minutes, because every African knows that shit. It’s not news,” he told Quartz in a recent interview in New York. “What I am interested in is how we create narratives that grow our continent and grow our conversations within each other.”

In the 10 years since the essay, Binyavanga would help found Kwani?, a literary magazine that has grown into one of the more vibrant publishing houses for young writers in East Africa.

He wrote a well-received memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place. Last year, he added another chapter to the memoir, a letter to his mom in which he would declare: “I am a homosexual.” Since the revelation, he has become a vocal advocate for gay rights.

And now, Binyavanga—as he’s affectionately referred to by his fans—is on another mission: To transform African publishing.

The Nollywoodification of the book market

How? Go all populist, do for publishing what Nollywood in Nigeria has done for the film industry. Estimates suggest that 1,500-2,000 films come out of Nollywood annually, contributing to 1.4% of Nigeria’s $522 billion GDP. The trick will be whether publishers on the continent can take these lessons and translate them to the book trade.

‘We are trying to think about how, not to adapt the Nollywood model but to create an equally mass-based, market driven, popular and affordable way to sell and distribute popular books,’ he says.

The current reality is such that there is a disconnect between publishers who produce books beyond texts for schools and their target readers. “What we have is a giant vacuum,” Binyavanga says. “If you are a bank manager and you want to buy books, where do you buy books? There is one bookstore in Nairobi that has meaningful selections.”

He points out another instructive model to think about: Penguin and the paperback. Their idea of publishing high literature for a mass audience revolutionized publishing. But what was impressive was the way in which the model expanded the pool of readers to folks who could now buy a copy of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms at the same price as a packet of cigarettes.

Data is scant when it comes to the number of books published in Africa. Estimates, nowhere near conclusive, suggest that the continent publishes between 2-3% of the world’s books.

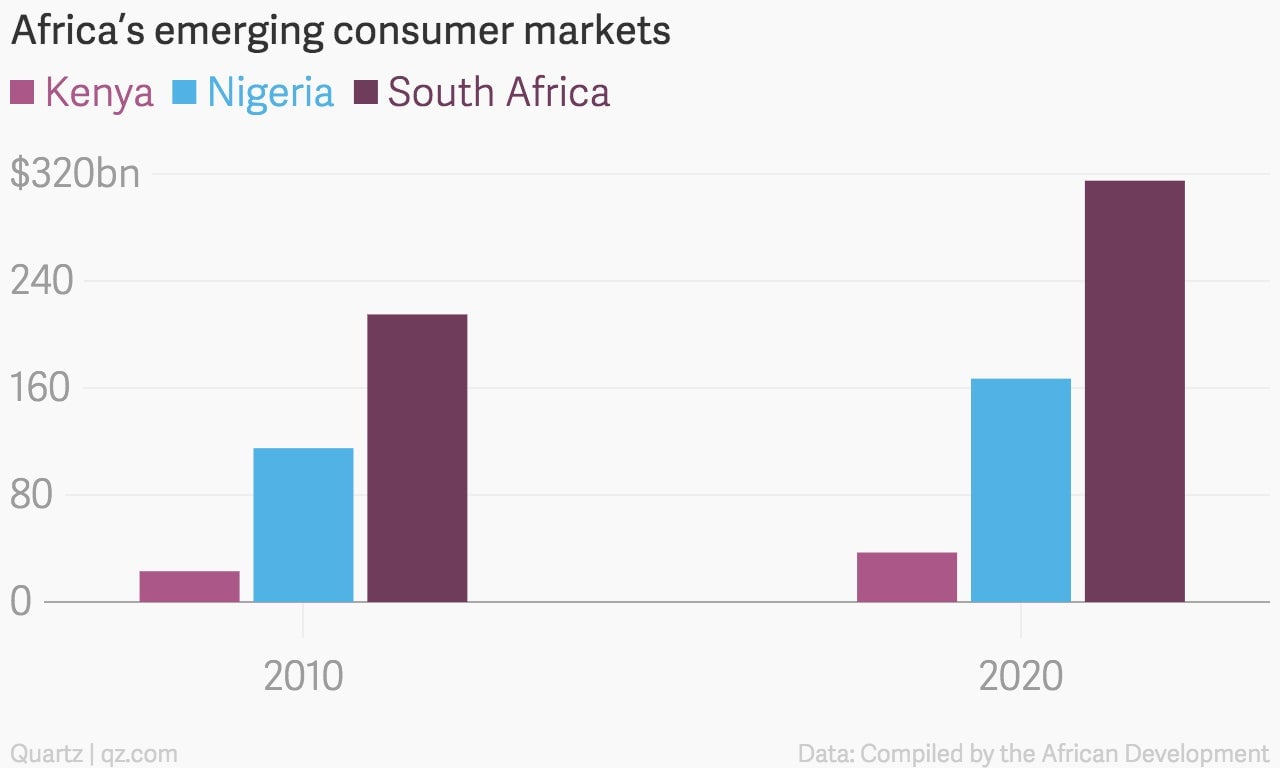

With the rise of digital platforms and an emerging middle class, there is an opportunity, Binyavanga believes, to transform the publishing business on the continent. But are publishers connecting the dots? Not quite. “Right now at the moment which I can scale up, make stuff happen, the marketplace somehow and us are not speaking the same language,” he says. “So the quest that I am on, and others are on, is to capitalize, and scale the production of books.”

The global resurgence of African literature

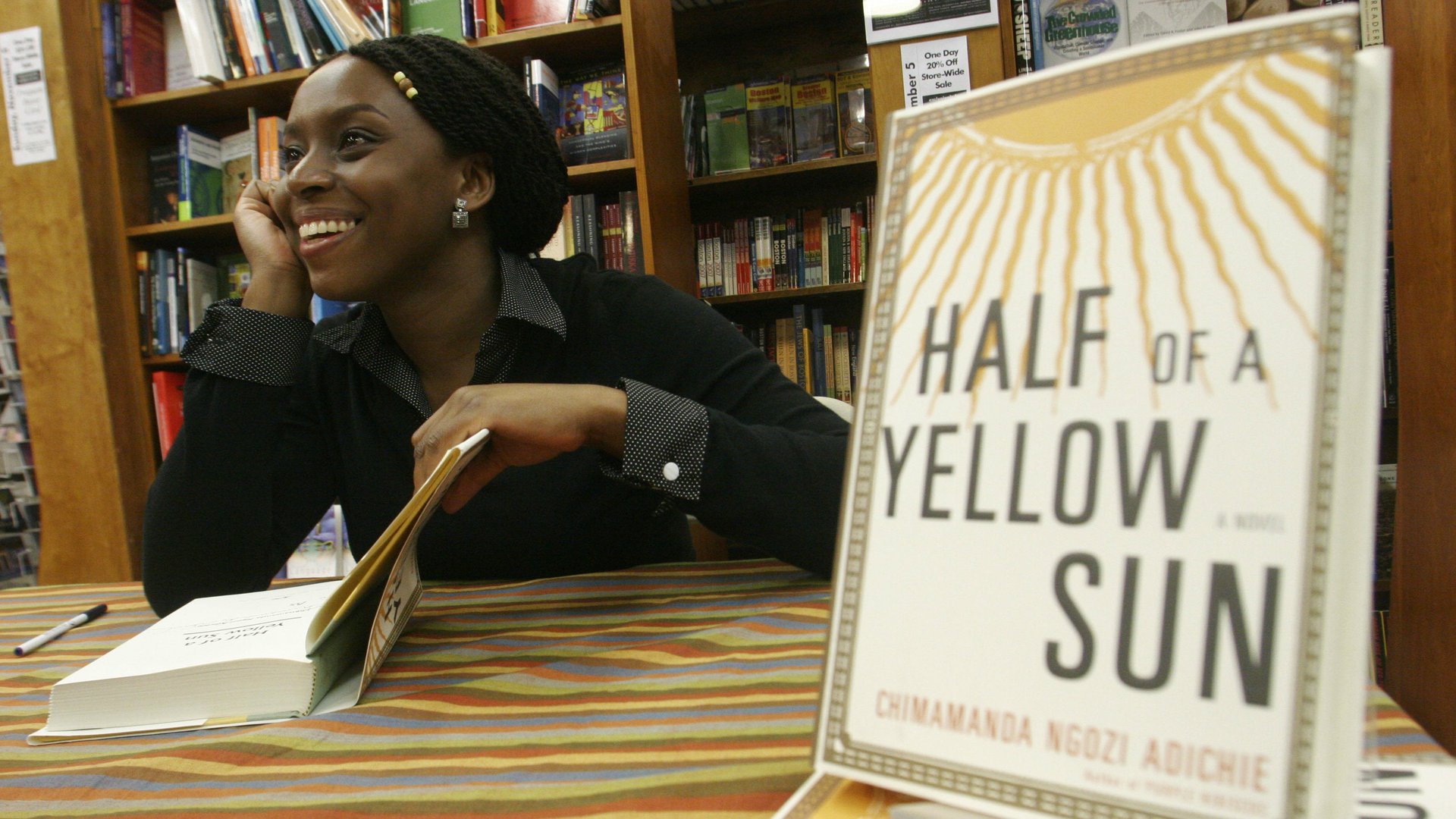

African literature is experiencing a renaissance on the global stage. The success of writers such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Teju Cole, NoViolet Bulawayo and others is re-framing the African narrative. As Binyavanga puts it, while Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o wrote about colonialism and post-colonialism, today’s African writer and her preoccupation can not be easily prescribed.

On the continent itself, there is a kind of arrival that is happening in the literary scene. “You have large platforms of thinking, communications, and distribution of ideas and people have become confident enough to say what is their burning issues,” Binyavanga says. “There are people who are like, I want to write epic poetry, and I just to do it online. There are people who specialize on sexually provocative Facebook posts, which are poetic. We are now past the point of the asking of theme.”

The task now is to tap into the experimentation in format and styles and to monetize the products. Binyavanga wants to bring together the Nollywood inspiration and the Penguin model together for the future success of literature on the continent. He is convinced that the tide of such an endeavor will lift all boats.

“When Penguin has all those mass books. That’s when they can go and buy that high poet, and pay him well, because they are making a profit down there,” he argues. “So this is the time that needs to be done.”