Science is warning us that a food crisis is coming to Southern Africa. Will we stop it?

In April, harvest season begins in Southern Africa. An ongoing drought means the season will yield a historically poor crop. Countries including Malawi, South Africa, and Zimbabwe will have major shortfalls of grain. By one count, more than 20 million people in the region already have limited access to food—notwithstanding the drought. Without intervention, the next year will put those people and millions more at risk of malnutrition or even starvation.

In April, harvest season begins in Southern Africa. An ongoing drought means the season will yield a historically poor crop. Countries including Malawi, South Africa, and Zimbabwe will have major shortfalls of grain. By one count, more than 20 million people in the region already have limited access to food—notwithstanding the drought. Without intervention, the next year will put those people and millions more at risk of malnutrition or even starvation.

But knowing all this makes intervention more possible than ever.

Famines are a powerful illustration of how suddenly nature can undercut a poor or poorly prepared society. We have paid dearly for our failure to respond to them efficiently. Economist Stephen Devereux has estimated 70 million people (pdf) were killed by famine in the 20th century alone.

Today, analysts employing new sources of information, better technology, and networks of human monitors have made it possible to foresee agricultural disaster far enough ahead so that resources can be mobilized to prevent starvation.

The impending food crisis in Southern Africa has yet to capture the international media’s attention, but it is the subject of ongoing analysis by a network of agriculturists, climatologists and economists. Global monitoring centers, such as the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS), issue regular updates. If the crisis does devolve into a famine, the world will have known it was coming for at least six months.

How to foresee a crisis

Many different organizations monitor food security around the world. FEWS is a collaboration between five US agencies and two private companies. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) hosts another group called the Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS). Each group gathers and analyzes data until they determine it is time to sound the alarm about an impending crisis.

Last year a powerful El Niño smothered Southern Africa with hot, dry air, prompting FEWS to issue just such an warning. Many areas experienced the driest start to the growing season in 35 years. South Africa had the least annual rainfall it’s had in a century (pdf). The drought delayed planting of crops by up to 50 days in some places. According to Christopher Hillbruner, a food security analyst at FEWS, that makes it impossible for the region to bounce back this year. ”Even if tomorrow it rained beautifully for two months, the crops aren’t in the ground, so it doesn’t matter,” he said.

Agriculture provides food, income and employment for 70% of the region’s population, according to the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Locally harvested grains, especially corn, are a key staple of regional diets.

The growing season for most grains, including corn, begins between October and December. Farmers harvest those crops between April and June. Any interruption of this cycle can have devastating consequences both for those rural subsistence farmers who feed themselves, as well as for urban residents who rely on food grown in the countryside.

Compounding the food supply problem, there was also a drought in the region last year. The cereal harvest in South Africa, the region’s largest producer, was down by more than a fourth from the year before.

Measuring a harvest before it happens

Satellite data is used to monitor the drought’s impact on agriculture. These “remote sensing” platforms measure changes in the air, land, and water through the spectral properties of the Earth. With decades of such measurements on file, it’s now possible not only to chart the temperature, precipitation, and other factors, but also how much today’s conditions deviate from historical norms. The following interactive map shows what proportion of normal rainfall Southern Africa has received over the last five months, using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization.

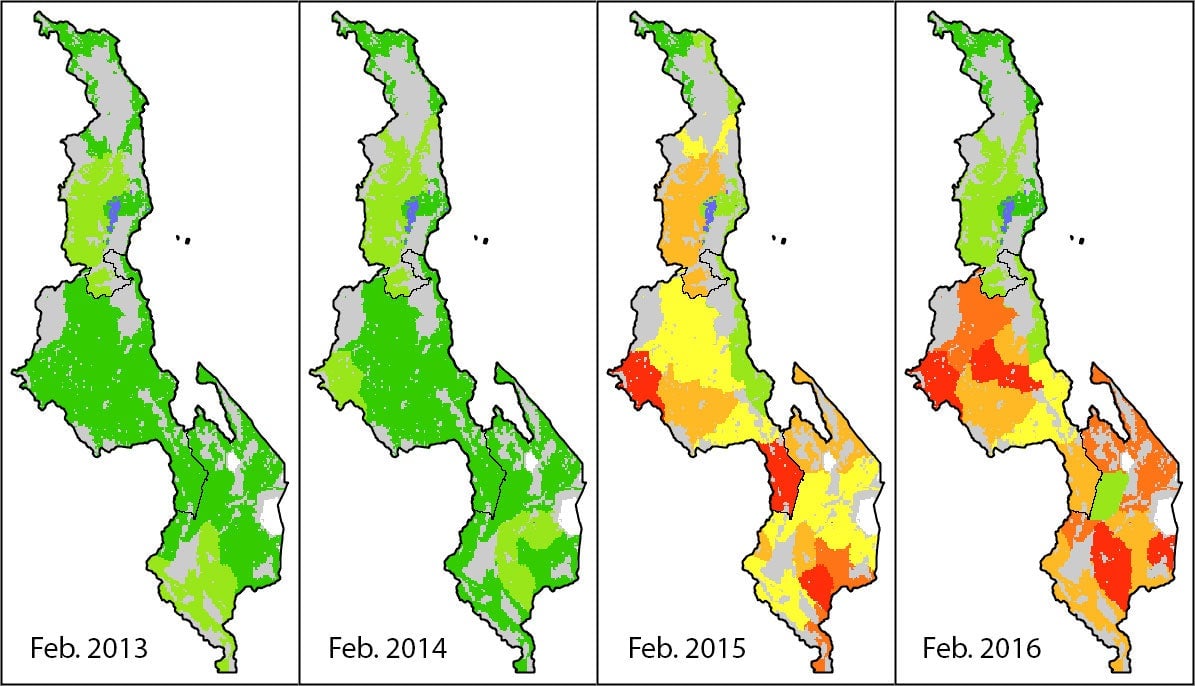

Researchers combine basic measurements to create more complex benchmarks of crop health. For example, the FAO uses an indicator called the Agricultural Stress Index (ASI) to quantify the cumulative stresses on crops. They publish ASI maps of every country in the world, three times a month, allowing for quick comparisons between different times and places. For example, the maps below illustrate the situation in Malawi at the height of the growing season, for each of the last four years.

This kind of climate analysis has developed significantly over the last decade, though Hillbruner is quick to note that improvements to FEWS projections haven’t come from big technological breakthroughs, but rather a steady progression of small changes. Their analysis relies on a “convergence of evidence” from many sources, including human monitors, where no single source is treated as authoritative.

Monitoring food economics

Projecting the future of food security requires looking closely at more than just weather. Even when food does make it to markets, it may be too expensive for subsistence farmers who have lost their main source of income to the drought. Economic variables, such as regional food reserves, transportation costs, and local price trends can be as important as crop yields.

Grain reserves will be one major difference between this year’s drought and last year’s. In 2014, a record harvest flowed into grain silos across Southern Africa. This provided an important buffer against food insecurity. Zambia, in particular, benefited from its reserves. It was able to support itself, while also exporting nearly 500 thousand metric tons to neighboring Zimbabwe.

Unfortunately, the leftovers from 2014’s banner year are now almost entirely used up. This year few countries have any significant stockpiles. Those countries that are able are already in the process of negotiating large-scale imports from Europe or South America. Lesotho, Malawi, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe have issued new appeals for humanitarian assistance since the onset of El Niño, according to GIEWS economist Jonathan Pound.

Production levels and stockpiles are the big picture for food security, but they don’t guarantee any particular price at the village market. Other factors, such as transportation, can cause local prices to change independent of national trends. Researchers at GIEWS and elsewhere are trying to better understand those local impacts by tracking prices within each country. Analysts monitor that data for sudden spikes and issue alerts when they happen. In response to food shortages and depreciating currencies the FAO issued price warnings for Malawi and South Africa in February (pdf).

Fortunately, while regional food prices are up, global food prices are way down from their peaks in the last decade. This may help offset some of the cost of large-scale food imports. Low oil prices will also reduce the cost of distributing imported food, which will further drive down prices for consumers.

Early warning provides an opportunity

According to Hillbruner, the worst of the food crisis won’t arrive until this time next year—just before harvest, when food stocks are most depleted. In a way, that’s good news. “There is an extended period of time before the worst outcomes come to pass, so we have relatively more time to act,” he said.

Food for Peace (FFP), an office within USAID, is the funder of FEWS. In an interview with Quartz, acting director Matt Nims said they’ve been able to make specific preparations based on FEWS projections, including ensuring they have fully-stocked pipelines of emergency food products, and stocking up on specific types of food in their warehouses, such as sorghum, something they wouldn’t have done in a ‘normal year.’

“It put Southern Africa on the watch as far as how much resources we’re going to dedicate,” Nims said.

Local organizers are also preparing. In late February, SADC, the World Food Programme, and the FAO agreed on ten short-term objectives, including collecting better data on those being affected and streamlining logistics for food distribution.

There are good reasons to believe that a famine can be prevented. Southern Africa faced a similar drought in 1992 and avoided a famine, despite the loss of more than half of its harvest. Imports and changes in local diets compensated for the diminished local food supply.

However, what is more likely to be the on the mind of humanitarians and policymakers is the 2011 Horn of Africa drought which did cause a famine—the worst to hit any part of Africa in many years. It killed as many as a quarter of a million people in Somalia. Humanitarian groups were widely criticized for reacting too slowly, though interference by the militant group al-Shabaab was also a major factor in keeping aid out of the hardest-hit areas.

Fortunately, Southern Africa’s governments are basically stable. Large-scale food imports are already being organized in many places and relief organizations are operating in the regions with the most immediate drought impacts. Unlike other parts of Africa, conflict is not a major barrier to aid distribution.

Even so, preparing for El Niño-related problems is complicated by the need to address more urgent food crises in Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Yemen. Planners worry that sounding the alarm about a future crisis can draw attention away from ones already underway.

In the long run, agricultural modernization, development of local markets, and other efforts to build up countries’ resiliency are the best solution to prevent famines. Until those efforts are further along, the world must continue to respond to the crises that inevitably arise.

It’s not yet possible to predict every outbreak of hunger before it happens. Wars erupt. Currencies collapse. Harvests fail in corners of world where monitoring programs aren’t yet active.”The world is a big place. I think we can always be surprised by things,” Nims told Quartz.

And yet, the science of famine prediction is the best it’s ever been. Year by year, data sources improve, as does understanding of the complex interplay between agriculture, climate, and economics. Advance warning may not be a magical solution that can prevent every famine, but at least in Southern Africa the world has both the knowledge and the capacity to prepare for one, and maybe even prevent it, long before it begins.