COP27: A shaky start

Plus: WTF happened to GFANZ?

Hello COP27 delegates and readers,

COP27 began in Sharm El-Sheikh with a notable if bureaucratic victory: “loss and damage” is on the official agenda (pdf) for the first time in 30 years of climate negotiations. The term describes payments that developing countries argue they should receive from developed countries to compensate for the costs of climate-related disasters. In June, a group of 55 vulnerable nations calculated the bill from catastrophes such as droughts and floods, and found it topped $525 billion over the past two decades, or about 20% of their GDP.

The placement of loss and damage on the official agenda means rich countries can no longer avoid the subject, unlike at past COPs. But Egypt’s foreign minister and COP27 president Sameh Shoukry swiftly tamped down expectations during a speech: The negotiations will focus on “cooperation and facilitation” rather than “liability and compensation,” a bit of compromise that means no developed country will receive a bill in Sharm El-Sheikh. Instead, negotiators will seek to establish a formal system for collecting and distributing loss and damage payments. That process will likely take a few more years, delaying urgently-needed aid.

That’s not a promising start, since raising cash is the summit’s main objective, said Mohamed Adow, director of Kenya-based advocacy group Power Shift Africa. “We have a timeline for something that will not accept liability for the polluters,” he said, “and doesn’t clarify what the final outcome will be.”

It’s too early to judge the outcome of the summit. Negotiations have yet to begin in earnest. Attendees were still spending much of Monday navigating the byzantine conference complex (pro tip: try finding the hidden Bedouin-style lounge tucked behind the European delegation offices). Hungry conference-goers also hunted for scarce provisions, mostly cheese sandwiches and mango juice. Even bottled water was in short supply.

The more serious issue dominating hallway chatter and press scrums was the fate of British-Egyptian dissident Alaa Abdel Fattah, one of thousands of political prisoners in Egypt. Abdel Fattah has been imprisoned outside Cairo for a decade for alleged political crimes. He is now more than 200 days into a hunger strike, and stopped drinking water when COP27 started. Abdel Fattah’s family has warned if Western leaders don’t escalate pressure on Egyptian president Abdel Fattah El-Sisi to release him, he may die before the summit ends.

“Egypt itself stands to benefit from the climate negotiations, but now all anyone is talking about is the human rights situation,” said leading rights activist Hossam Bahgat, who managed to secure access to the COP through a German NGO. “It’s a full-court press to save his life.”

What to watch for

🤞What will happen to Alaa? British prime minister Rishi Sunak said he planned to raise the case with Sisi during a Nov. 7 bilateral talk. But the case is deeply personal to Sisi, and there’s little indication he is willing to budge. In the meantime, Abdel Fattah’s family has no way to consistently monitor his health or ensure he’s alive.

👄 What else will world leaders say? French president Emmanuel Macron raised eyebrows during a Nov. 7 speech accusing the US and China of falling short on their financial obligations (France is a major climate finance donor). Other heads of state speaking on Nov. 8 include Senegal’s Macky Sall, who will likely address the role of fossil fuels in Africa’s economy; Pakistan’s Shehbaz Sharif on that country’s recent devastating floods; and Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy via video.

💰Which other countries will get cash to cut coal? Last week South Africa unveiled details of a plan to transition away from coal-fired electricity using $8.5 billion raised by donor countries in Europe and elsewhere. That program, called the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), was originally conceived at COP26 and meant as a blueprint other fossil-reliant developing countries could follow. New JETPs are expected during COP27 for Vietnam, Indonesia, and possibly others.

WTF happened to GFANZ?

During COP26, banks and other financial institutions basked in publicity after forming the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, a group of global asset managers claiming to align their $130 trillion portfolios with decarbonization goals. Since then, the group has faltered, setting weak goals, nearly losing key members, and cutting ties with a UN campaign pushing science-based climate targets just before COP27. But GFANZ will have a chance to restore its reputation on Nov. 9 at this summit’s Finance Day. For now, it’s just greenwashing.

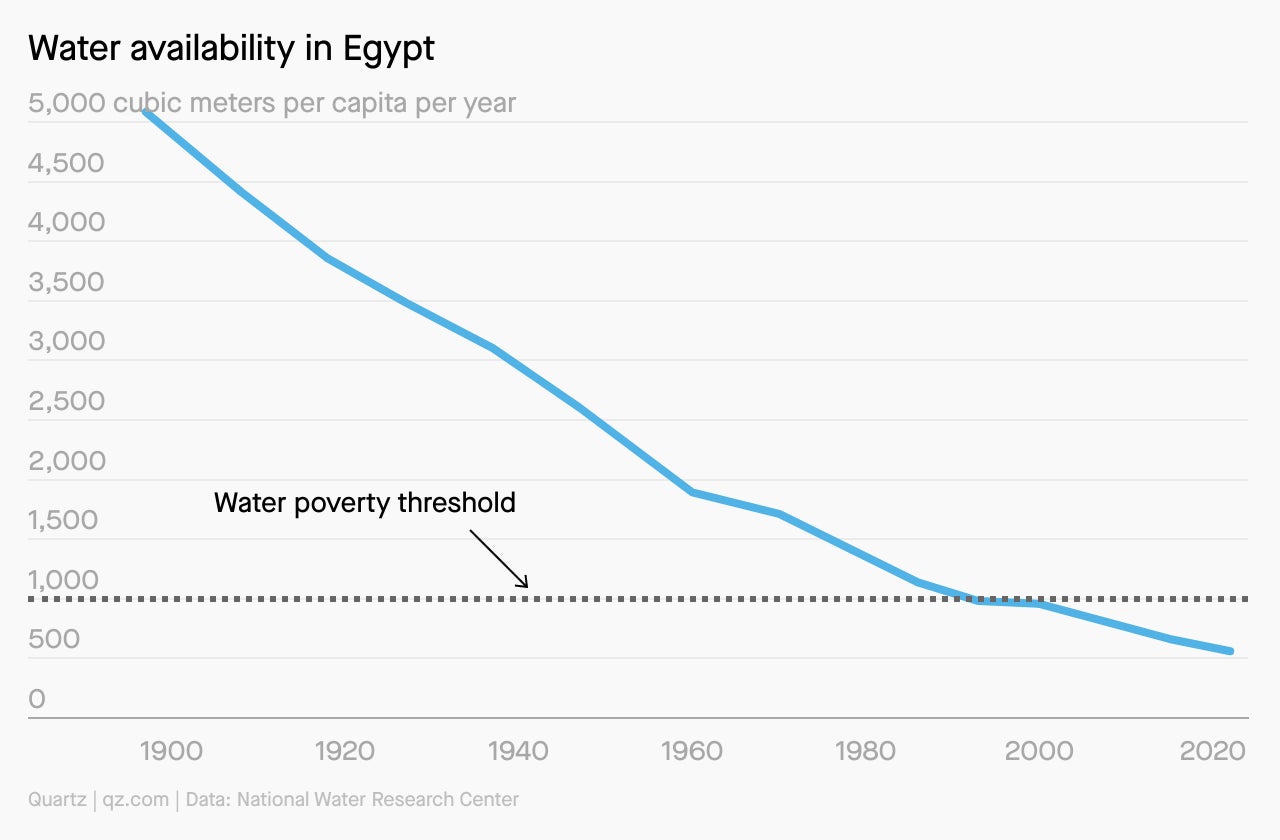

Charting Egypt’s water crisis

As host of COP27, Egypt has plenty of its own climate problems to worry about. The most important is water scarcity: 95% of the country’s water comes from the Nile. Battered by upstream droughts, heatwaves, and population growth, Egypt’s water availability per capita has plummeted well below the “water poverty” benchmark. In a feature story produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center, Quartz found that Egypt’s Nile Delta isn’t prepared for climate change.

Quotable

“How do oil and gas companies make $200 billion in profits in the last three months and not expect to contribute at least 10 cents on every dollar to a loss and damage fund?”

—Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, in her Nov. 7 address to the COP

Mottley, whose island nation is on the front lines of climate change and weighed down by debt from climate disasters, has become a champion of creative approaches to raising more climate finance, including potentially taxing oil company profits and placing the proceeds directly into a loss and damage fund.

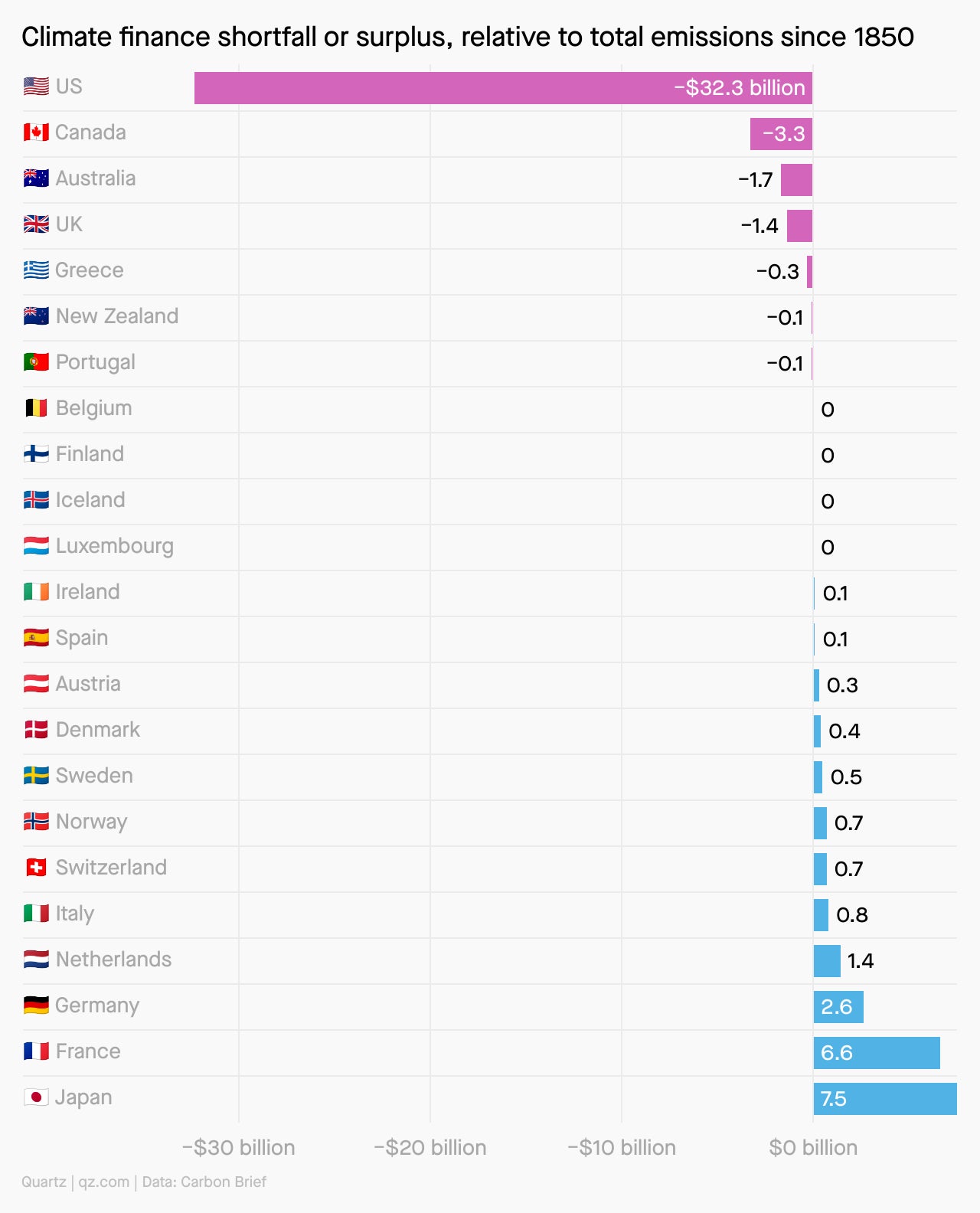

Which countries are contributing their fair share to climate finance?

Some of the world’s major greenhouse gas emitters aren’t contributing nearly enough to their “fair share” of climate funding. Relative to their historical emissions, the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK are tens of billions of dollars short of meeting funding goals for developing nations, according to a new analysis from Carbon Brief.

These imbalances are based on the $100 billion annual climate finance target for 2020 that developed countries set at COP15 in 2009. This goal hasn’t yet been met; only between $21 billion and $83 billion (depending on how the funds are counted) was secured in 2020. If the US were to give its “fair share”—the portion of funding equivalent to its historical share of emissions—it should have contributed $39.9 billion in 2020. In reality, it contributed $7.6 billion.

Thanks for reading! We’ll be back in your inbox in a few days with the latest updates from COP27. Stay tuned.

— Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter; Michael J. Coren, deputy editor of climate and emerging industries; Amanda Shendruk, visual journalist; and Morgan Haefner, deputy email editor.