COP27: Extreme makeover, climate finance edition

Plus: The 1.5 °C countdown begins

Hello COP27 delegates and readers,

Climate finance needs an extreme makeover.

Developed countries still haven’t kept their end of a 2009 deal to raise $100 billion annually to help developing countries transition to clean energy and adapt to climate impacts. That was supposed to happen by 2020, but funding remains $17 billion to $79 billion short (depends on who’s counting).

At COP27, negotiators are already working on a new goal to replace the $100 billion one, which will take effect by 2025. No numbers are on the table yet, but one thing is clear: The old approach to climate fundraising isn’t going to cut it. “The simple political will that’s necessary to not just make promises, but deliver on them, still seems not capable of being produced,” said Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, during a speech last week.

Mottley has seized the spotlight at COP27 to push for a package of reforms—known as the Bridgetown Initiative, after her country’s capital—that aims to rewire the global financial system so that billions or even trillions of additional dollars could be on the table for climate-vulnerable, debt-strapped countries like hers. These include deferring sovereign debt payments in the aftermath of natural disasters, using special low-cost loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and stepping up the World Bank’s tolerance for investment risk.

She’s not just shouting into the void. Leaders in the US and Europe who heavily influence policy at those institutions are listening, for a change.

“For the first time, really transformational changes to the global financial architecture are being taken seriously,” said Franklin Steves, senior policy advisor on finance at the European climate think tank E3G. “There’s quite a revolutionary set of proposals on the table, and an unprecedented set of lower, middle, and high-income countries coalescing around them.”

What to watch for

💰 Can countries agree on loss and damage? This issue—how much rich countries should pay for climate damages in poorer ones—remains the most controversial of COP27. On one side, developing countries are insisting on a commitment from developed countries that a special fund will be created to handle these costs. On the other side, developed countries argue that other sources of finance could suffice—and that in any case, the pool of donor countries should be expanded to include the likes of China, with funds reserved only for the very poorest. If anything pushes COP27 into overtime, it will be this.

🛢️ Will COP27 call for a phasedown of oil and gas? Another key issue—and litmus test for Egypt’s dealmaking prowess—will be any potential mention of fossil fuels in the final “cover text” summarizing the outcomes of the COP. Many countries, including the EU and India, support language calling for all fossil fuels to be phased out, building on a statement from the G20 this week that specifically mentioned coal. But the end of oil and gas may be too much for Saudi Arabia and other big exporters to accept.

🌳 Will COP move to the Amazon? The big celebrity on campus Nov. 16 was newly-elected Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has promised to reverse his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro’s shoddy climate record and reinvigorate conservation efforts in the Amazon. Although Lula didn’t make any new announcements, he did offer to host an upcoming COP in the rainforest.

Fish can help Egypt save water

COP host Egypt has a major, chronic shortage of water. Building onshore fish farms might not seem like an obvious way to solve that problem, since they’re, you know, filled with water. And yet, that’s just what some scientists and investors are pushing for in the country’s Nile Delta, arguing that fish farms have a much lower water and carbon footprint per kilo of protein than wheat, rice, or other typical staple crops. But government policies threaten to curtail the nascent industry’s growth.

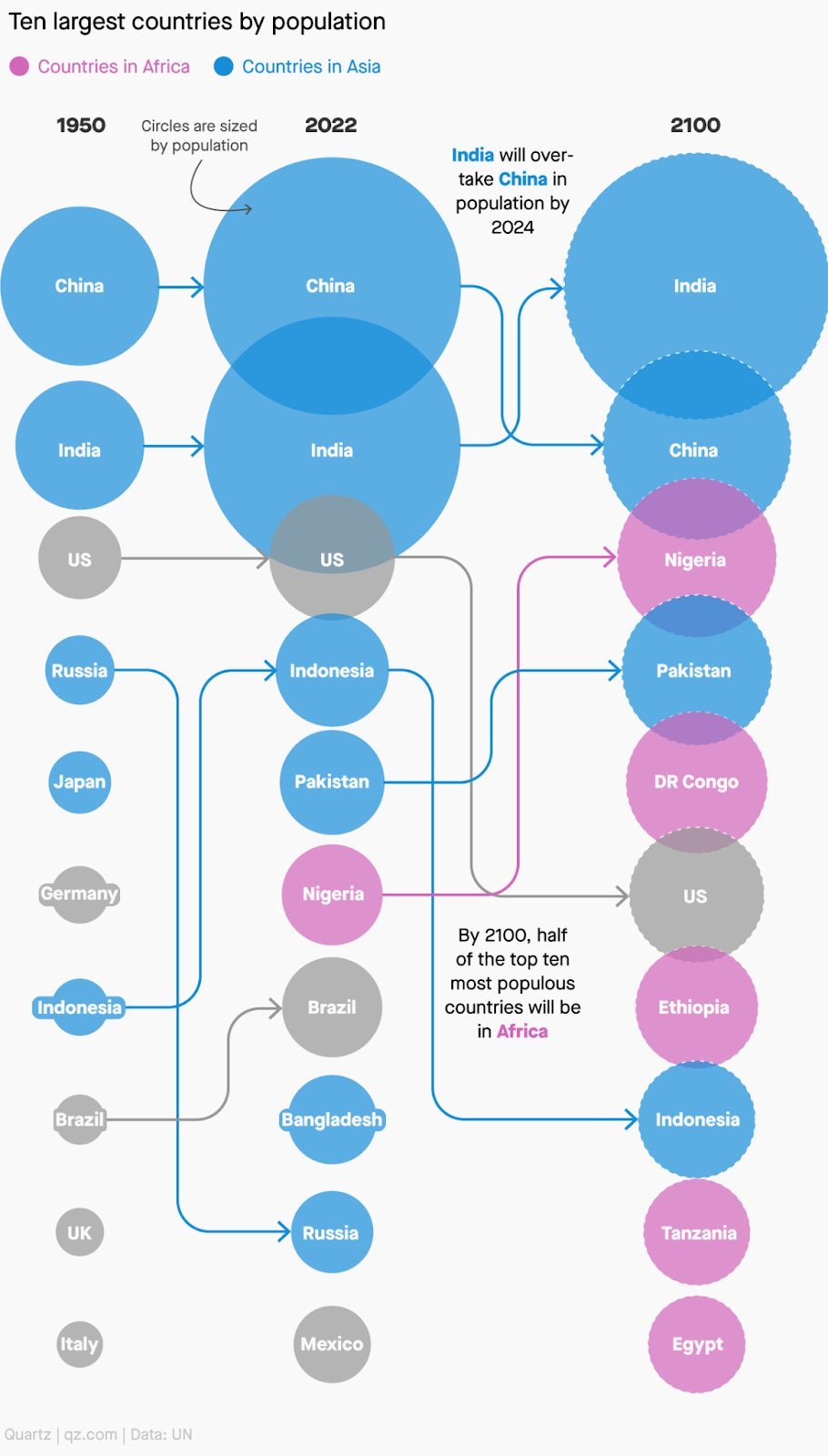

Eight billion and counting

The world hit a significant milestone this week—the global population reached 8 billion for the first time ever. Despite the increase, growth is actually slowing. At the present rate, we can even spot a peak: 10.4 billion or so, arriving sometime between 2080 and 2100.

For Africa, this growth presents a giant dilemma. African nations will drive half of the world’s growth in population between now and 2062. As hot, low-income countries, they are first in line to suffer from the dramatic effects of climate change, despite being among the least responsible for carbon emissions. At the same time, these countries will need to grow their economies to make the most of their population boom.

Quotable

“Long term, ultimately, the technical ‘unlock’ for long-haul flying has yet to be identified... Everything is in play, from propulsion to actual airframe design and other critical systems. There isn’t an exact line of sight today.”

—Pam Fletcher, Delta Air Lines chief sustainability officer

Fletcher, who joined Delta recently after leading the charge toward electric vehicles at General Motors, has a tough job. The global aviation industry emits about as much greenhouse gasses annually as Germany, but technology to fully decarbonize airplanes is much less advanced than the technology for cars. In an interview, Fletcher said she wants to curb Delta’s reliance on carbon offsets and focus on near-term steps to trim emissions. But the path to full net-zero remains unclear.

This one trick to cut emissions

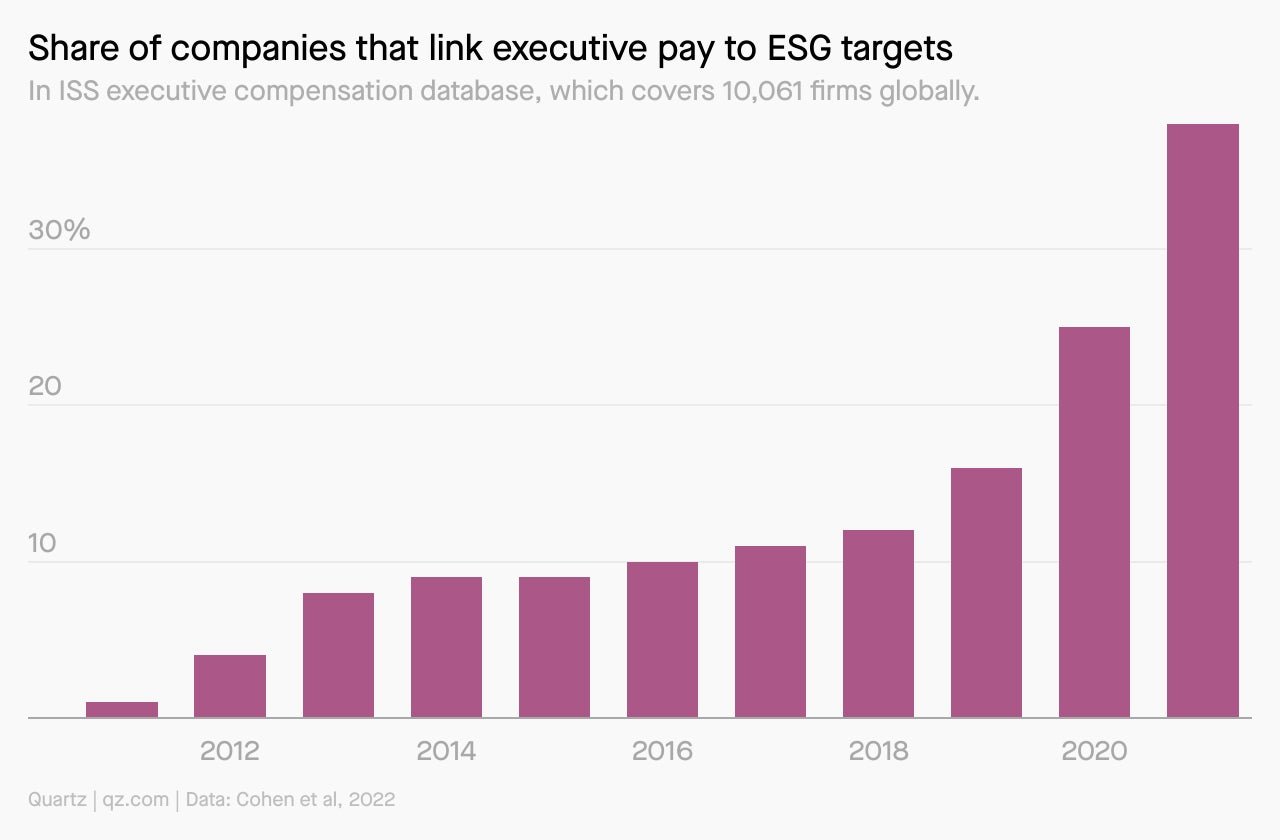

In addition to investing in greener technologies and carbon offsets, more companies are tackling the issue of climate change by linking executive compensation with meeting environmental, social, and governance, or ESG, targets.

While you can bet ESG pay metrics won’t be coming to Twitter anytime soon, their popularity is only growing: 40% of companies were using them in 2021, up from just 1% in 2011, according to a working paper (pdf) by economists in California and Europe.

There are signs it works. Most companies that adopted ESG-linked pay saw lower emissions and higher ESG ratings from third-party agencies within a couple of years after adoption. Bonus: they didn’t see any knocks on income from using the method.

Pop quiz: Setting the countdown clock

A paper released on the sidelines of COP27 this week suggests the world has very little time left to limit significant global warming. At the current rate of emissions, the Paris Agreement goal of keeping global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels will likely be out of reach in a handful of years.

The new study concludes that, starting in 2023, if the world produces 380 billion more tons of CO2, the odds of limiting warming to 1.5C will fall below 50%. At the current pace, how many years will that take?

A. 9 years

B. 12 years

C. 15 years

Oh, and for our previous pop quiz about which country sent the largest national delegation to COP27, the correct answer was the United Arab Emirates, the host country for next year’s COP28, with just over 1,000 participants. If the quiz was a test, y’all barely passed: 61% got the answer right, 19% thought it was China, and 20% thought it was Brazil. Better luck this time.

Thanks for reading! We’ll be back in your inbox one last time with our final update from COP27 (I know, we’re sad too). Have you liked our series so far? Sound off in our survey—we promise it’s quick and helps make our emails even better.

—Tim McDonnell, climate and energy reporter; Michael J. Coren, deputy editor of climate and emerging industries; Amanda Shendruk, visual journalist; and Morgan Haefner, deputy email editor.