Coronavirus: That’s it, we’re grounded

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

Before we get into anything today, let’s try a meditative exercise. Close your eyes (or um, finish reading this, then close them). Take five deep breaths, and picture a stream. Along that stream are all your stresses—there’s coronavirus, of course, and market volatility. There’s your mother-in-law sending shady hand sanitizer recipes to the family group chat. There’s the uncomfortable chair you have to work from at home. Now picture each of these anxieties floating right by you, down the stream. Open your eyes. Remember: The stream will keep flowing, even if you’re not tracking every anxiety closely.

Keep your mind clear, but also tell us what’s on it. Please send questions, thoughts, or legit hand-sanitizer recipes to [email protected]. Let’s get started.

MOOCs of hazard

As Covid-19 reaches pandemic status, hundreds of universities around the globe are closing their physical doors and opening virtual ones, inviting temporarily evicted students to log in to classes from home. While no one wanted coronavirus, it is proving a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for online learning.

MOOCs, or massive open online courses, were originally born a decade ago to democratize access to higher education. In 2012, CS221: Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, a graduate-level course taught by Stanford professors Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig, attracted 160,000 students from 190 countries, with more than 100 volunteers translating the lectures into 44 languages, including Bengali. Around the globe, students and teachers began rushing headfirst into the world’s largest ed-tech experiment.

But MOOCs ran into a wall. (No, it wasn’t the acronym.) As it turns out, very few learners actually finished the courses they started. One study, by academics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, found that online courses had an astronomical dropout rate: about 96% on average over five years. Today, many MOOCs have tweaked their business models: charging fees, tracking metrics other than completion rate, offering “nanodegrees” so students will stick it out, and partnering with traditional schools to offer MOOC-based degrees online.

That has positioned them well for this crisis. Between January and February, US-based online education company Coursera saw a 47% spike in enrollments in China and Hong Kong, and a 30% jump in Vietnam, all countries impacted by the Covid-19 outbreak. (In China and Hong Kong, there was also a 185% jump in enrollments for public health content.) On March 12, Coursera announced that it will provide any impacted university in the world with free access to its 3,800 courses.

“We’re in a moment when coronavirus is forcing some rapid experimentation with educational technology that might have otherwise taken years if not not decades to happen,” says Leah Belsky, chief enterprise officer at Coursera. That’s a good thing, she adds, “because the education system has two key problems. One, there’s a profound lack of access to higher education, and more technology adoption can enable more access. And there’s a big problem with quality.”

Both of those will now be tested at scale.

Not coming to America

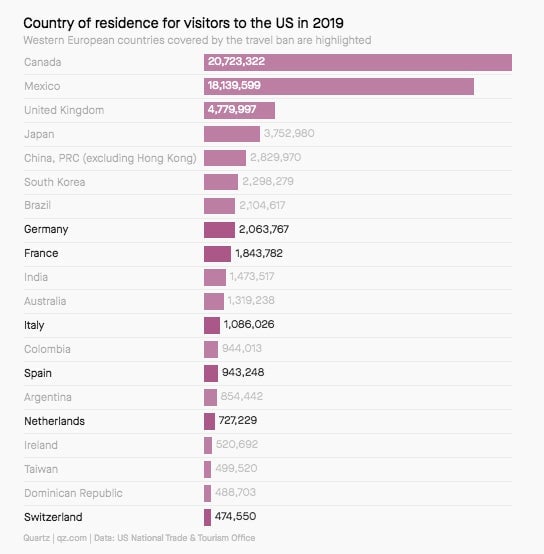

On any given day last year, about 25,000 European residents—that excludes the UK—arrived in the United States. Starting today and for the next 30 days, all such journeys are off. Earlier this week, US president Donald Trump announced a ban on incoming travel (except by US citizens) from 26 European countries, including six of the top countries that send their residents over to visit Uncle Sam.

The travel industry is already feeling the burn. Airlines and their share prices have spent a month limping along. These new restrictions will affect 3,500 flights per week and up to 800,000 passengers, according to aviation analysts at Bernstein. Those airlines most affected are likely to be the ones running regular transatlantic routes, including Germany-based Lufthansa and Air France-KLM, which has its headquarters in the Netherlands. The already-troubled Norwegian Air is laying off 50% of its staff, and Delta announced dramatic plans to eliminate flights to Europe, and reduce overall capacity by 40%.

Dire education

On Wednesday, the WHO finally labeled the novel coronavirus a pandemic. But history is no stranger to global disease outbreaks, and each one teaches us something about how to manage their spread.

- Antonine plague, ~165-180 and ~250 AD: A form of smallpox or measles was brought to Rome by legionnaires returning from a siege in modern-day Iraq. Lesson: Outbreaks are deadliest when introduced to a population for the first time.

- First influenza pandemic, 1580: The first true flu pandemic spread from Asia through trade routes into Europe—which began to execute some of the first quarantine measures and border checkpoints around this time.

- 19th-century cholera pandemics, 1800s: At least six distinct outbreaks of cholera started in the Bay of Bengal region of India, and spread along colonial trade routes. Misinformation and resentment over economic inequality exacerbated the threat, but researchers developed key insights on contact tracing—one London outbreak was traced to a contaminated water pump handle.

- Spanish flu, 1918: Likely the worst medical disaster in history, killing up to 50 million. The pandemic revealed just how many lives can be saved by social distancing: Cities that canceled public events had far fewer cases.

- Mid-century flu pandemics, 1957 and 1968: The last major flu pandemics were both derived from avian flu, and killed more than 1 million people. But the numbers could have been much higher without advances in immunology and diplomacy: By this time, both the flu vaccine and the WHO had been developed.

- HIV/AIDS, 1970s-present: Up to 32 million have died from HIV-related illnesses. Although the pandemic led to critical medical advances in antiretroviral drugs, and public health programs like needle exchanges and the widespread use of condoms, it also taught us a lot about the deadly danger of social stigma.

Cleaning house

Quartz’s New York HQ is getting a deep clean today, because you can never be too safe. What exactly is a “deep clean”? In this case, it means using an electrostatic spray gun to blanket all surfaces with hospital-grade disinfectants. The “electrostatic” part refers to an electrical charge that’s added to the cleaning solution, which makes it adhere to every surface.

This type of cleaning is in high demand. Calls to GermBlast, a Texas-based provider of commercial cleaning services—and authorized distributor of the Victory electrostatic sprayer—have quadrupled in recent days.

“Electrostatic sprayers are on backorder until June,” says GermBlast VP Christy Haynes (who was on the other line with the US Department of Homeland Security when we reached her). “We have people calling from everywhere, trying to purchase them. We have people calling for hand sanitizer, we have people calling for wall-mounted sanitizer units, but everything is on backorder. We’re having trouble getting this stuff ourselves.”

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 137,445 confirmed cases; 69,779 classified as “recovered.”

- Age of innocence: Sobering ethical choices are posed by Covid-19’s impact on different generations.

- Cash in hand: There’s no evidence that physical money can carry coronavirus.

- Uhhhh: A conspiracy theory linking the US army to the coronavirus now has official Chinese endorsement.

- Sorry, cats: The WHO says pets don’t need to social distance.

- Stay with me here: Does coronavirus need a brand?

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Jenny Anderson, Tim McDonnell, Whet Moser, Patrick deHahn, Justin Rohrlich, and Kira Bindrim.