Coronavirus: If you have to mask

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

You may have heard: Masks are in. On Friday, the US Centers for Disease Control updated its prior guidelines and recommended everyone wear cloth face masks in crowded public settings. It’s a big change for the country now leading the world in confirmed cases. What we know about the coronavirus is changing daily.

Let’s get you up to speed.

Maskimizing your chances

Back in January, asking eight health authorities if you should wear a face mask would elicit eight different answers. For decades, multiple studies have confirmed that masks are effective for healthcare professionals, and governments in China and Japan were quick to suggest or even mandate donning disposable masks to combat coronavirus. But Germany’s Federal Ministry of Health warned that mask wearers risked lulling themselves into a “false sense of security.” America’s top health official, battling a catastrophic shortage of masks for healthcare workers, tweeted in February for people to “STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing the general public from catching #Coronavirus.”

Just over two months later, there is growing consensus that wearing a mask in public is a good idea. The CDC (and now several nations in Europe) are asking people entering spaces where they can’t maintain at least six feet of distance to go ahead and put one on. So what changed?

Like influenza and other viruses, the coronavirus spreads through the diffusion of millions of tiny viral particles. After someone coughs, sneezes, touches an object, or even speaks, these particles can settle on a surface or hang briefly in the air, primarily in droplets. Viral particles, as many as tens of thousands per droplet, gain access through our nose, mouth, or eyes after we touch our face or breathe while in close contact with someone who is contagious. If the dose is high enough—and a single droplet may do it—the virus can replicate in our body, starting the infection cycle again.

The evidence is clear that the coronavirus can be spread by people who don’t have visible symptoms, like coughing and sneezing. That makes wearing a mask an easy (though not surefire) way to reduce the spread of viral particles. Like hand-washing and social distancing, masks are an extra layer of insurance, and public health authorities are looking for all the insurance they can get.

There is an important caveat here: Only medical professionals—who work in far riskier environments than most of us—should wear surgical and high-filtration N95 masks, as the WHO emphasized in new guidance on Monday. For the healthy general public, homemade cloth masks are okay. Almost every version of mask appears to confer at least some level of protection.

The many faces of face masks

- Cloth masks help to protect others from your outgoing germs, but they don’t protect well against incoming germs (especially when the fabric is damp). And not all cloth is made equal: Researchers are testing which fabrics might provide the most protection, and some DIY designs incorporate paper filters within cloth.

- Medical-grade surgical masks are made from melted, synthetic fibers shaped into an extremely fine web. This web allows air to pass through while filtering out particles. Surgical masks fit loosely on the face, so they can keep medical workers from infecting others, but don’t provide as much protection from infection as…

- N95 respirators, which are designed to fit so they form a seal around the nose and mouth. The 95 means they can block at least 95% of incoming particles as small as 0.3 microns. Sometimes these come with a valve to make breathing a little easier.

- KN95 respirators are similar to an N95, but they meet slightly different specifications set by the Chinese government. On Friday, the FDA announced it would allow their use in the US. The European-regulated version is called an FFP2.

The medical mask market

Medical mask manufacturers such as 3M and Honeywell have quickly ramped up production, but it’s not enough. Even China, the world’s largest producer of medical masks, ran short during its infection peak.

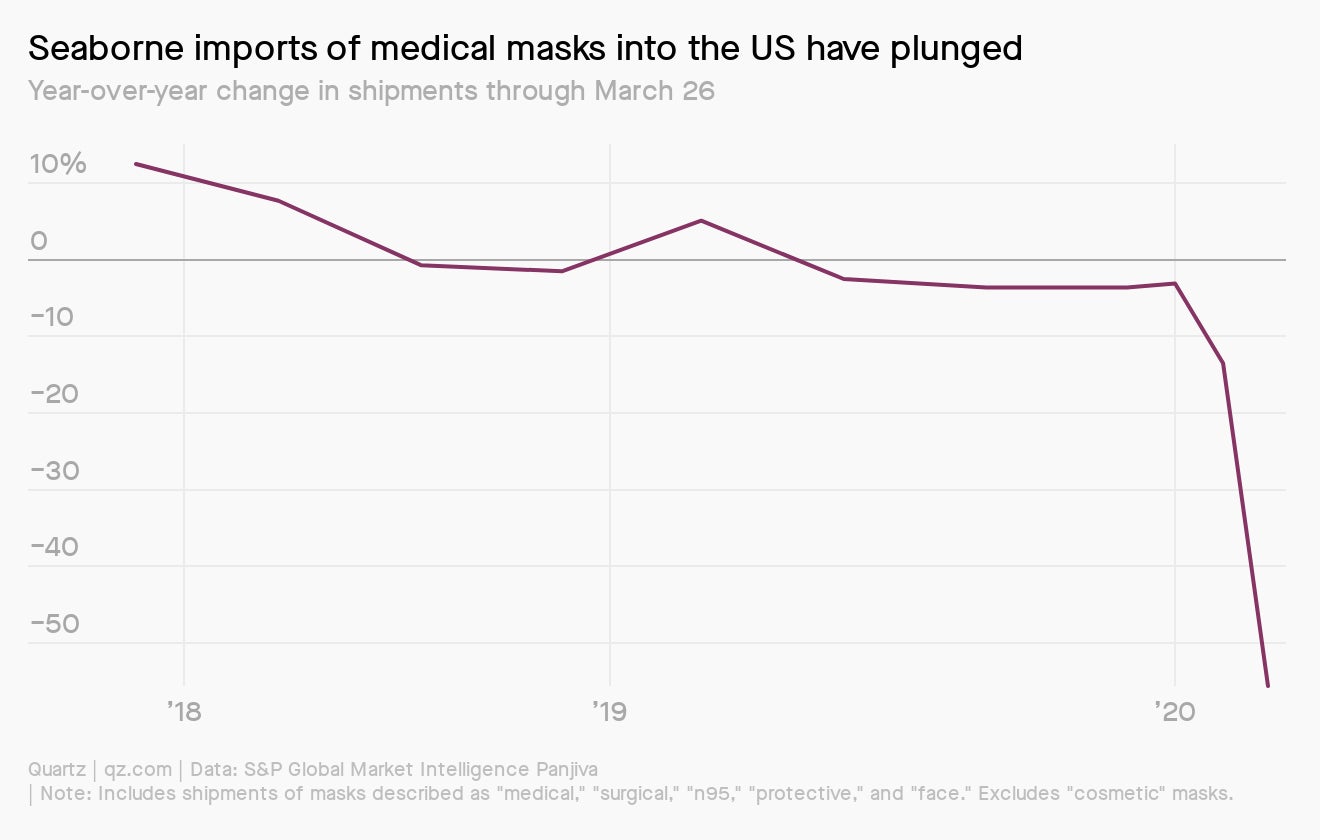

The US gets much of its supply from China, and while China says it hasn’t banned mask exports, North American suppliers have reported trouble getting shipments. Data provided to Quartz by Panjiva, a global trade platform that tracks shipping records, found seaborne shipments of medical masks to the US plummeted in March. One reason for the steep drop is that Panjiva’s data doesn’t include air freight. Companies—and as of March 29, the federal government—have begun airlifting supplies to cut their delivery time.

Big in Japan

Japanese consumers buy millions of surgical masks a year, but their utility is almost secondary to other reasons—historical, cultural, and societal—for their popularity. Here are some of the moments that pushed Japan toward a culture of regular mask-wearing.

1918: The Spanish flu killed between 20 million and 40 million people around the world—more than died in World War I. Covering the face with scarves, veils, and masks became a prevalent (if ineffective) means of warding off the disease.

1923: The Great Kanto Earthquake triggered a massive inferno that consumed nearly 600,000 homes, impacting air quality for months afterward. Face masks came out of storage and became a common accessory on the streets of Tokyo and Yokohama.

1934: A second global flu epidemic led to regular mask-wearing during winter months—primarily, given Japan’s obsession with social courtesy, by cough-and-cold victims seeking to avoid transmitting their germs to others.

1950s: Japan’s post-World War II industrialization led to rampant air pollution and booming growth of the pollen-rich Japanese cedar, which flourished due to rising ambient levels of carbon dioxide. Mask-wearing went from seasonal affectation to year-round habit.

You gotta mask yourself

Not every company can make medical-grade masks, but many are making the cloth masks needed to serve the general population. Among them: Nordstrom, Hanes, Fruit of the Loom, Fanatics, Neiman Marcus, JoAnn Stores, and Eddie Bauer.

You can also make your own mask, or sew some to donate to hospitals that need them. And don’t hesitate to make it fashion. Feeling newly vindicated about her habit of saving sewing scraps, Tokyo-based reader Jonelle P. has been churning out stylish masks for weeks.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 1,407,123 confirmed cases; 297,934 classified as “recovered.”

- Face it: Why one black man doesn’t feel safe wearing a mask.

- Spreading maskinfo: Facebook threatened to ban DIY mask-makers.

- Feeling the burn: The Burning Man community is helping get masks to hospitals.

- Naturally: The rise of the designer face mask.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Michael Coren, Marc Bain, Justin Rohrlich, Katie Palmer, Hailey Morey, and Kira Bindrim.