Coronavirus: Can’t hardly rate

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

Another week of too many questions and too few answers. Chief among them the enduring mystery: Is it better to be a dog or a ghost?

Earlier this week, we asked which you’d rather be, and the results were… unhelpful? We’re talking an exact 50/50 split, with impressively thought-out responses on both sides.

- Robert: “Dog. Ghosts aren’t real.”

- Phil: “Ghost. I’d be able to travel and I wouldn’t need to sniff every crotch that I encountered.”

- Peter: “Dogs have the infectious and spontaneous joy that only a perpetual 3-year-old can experience. Ghosts only moan on about how great life used to be. Dogs are happy to see you again every single time they turn their head. Ghosts are the actual embodiment of separation anxiety.”

- Katherine: “Would I haunt my enemies? Of course I would. But I wouldn’t terrorize them. I’d just…mess with them. Move their keys to a different spot when they aren’t looking, that sort of thing.”

The debate rages on—as does the poll: 🐶 dog or 👻 ghost—but the important thing is that we all stopped thinking about coronavirus for a minute.

That’s over now! Let’s get started.

Rate expectations

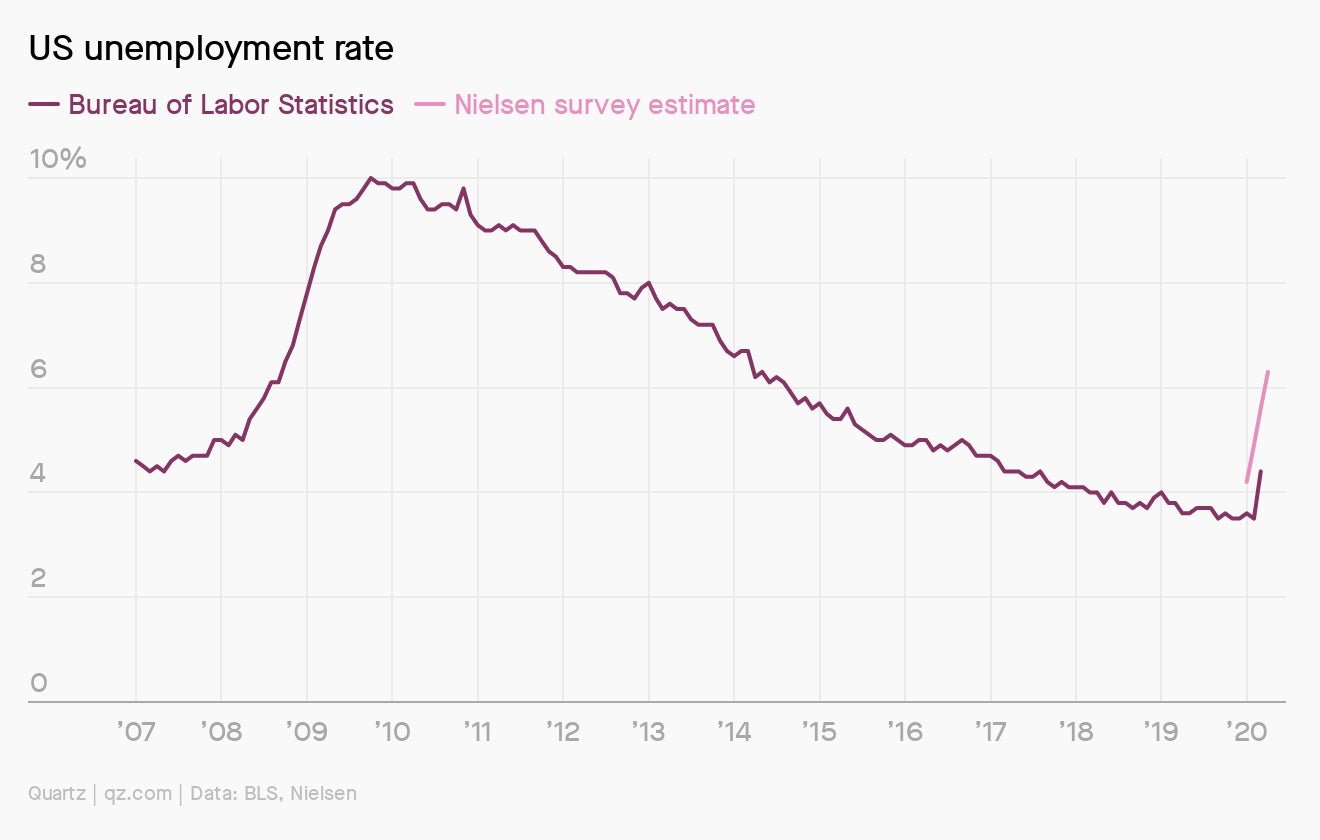

In January 2020, the US unemployment rate was at 3.6%. From January to early April, about 20 million Americans lost their jobs, according to a new study on the employment impact of the coronavirus pandemic. This suggests that about 8% of all people employed in January are now jobless. Yet the researchers project that the unemployment rate in April will be around 6%, just a two-percentage-point jump from January. How does that math add up?

The headline unemployment rate reported by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is calculated by taking the number of people looking for work and dividing that by that same number plus the number of people employed. For example, in January 2020, BLS found that 5.9 million people were looking for work, and about 164.6 million were either looking for work or employed, so the unemployment rate was 5.9 million/(164.6 million + 5.9 million), or 3.6%. Though the unemployment rate is not a perfect measure because it excludes some people who have been discouraged from looking for work, it usually is a pretty good barometer of the health of the job market.

The problem with using the unemployment rate formula at the moment is that only a small portion of the 20 million who lost their jobs because of the crisis are looking for work. According to this study, many of them are either waiting to return to their old job, or delaying their search until the economy goes back to normal. As a result, the unemployment figure will not capture the scale of this job-market calamity. The number of people who do actually want work, but are discouraged from looking, is exceptionally high at the moment, exacerbating the unemployment rate’s biggest flaw.

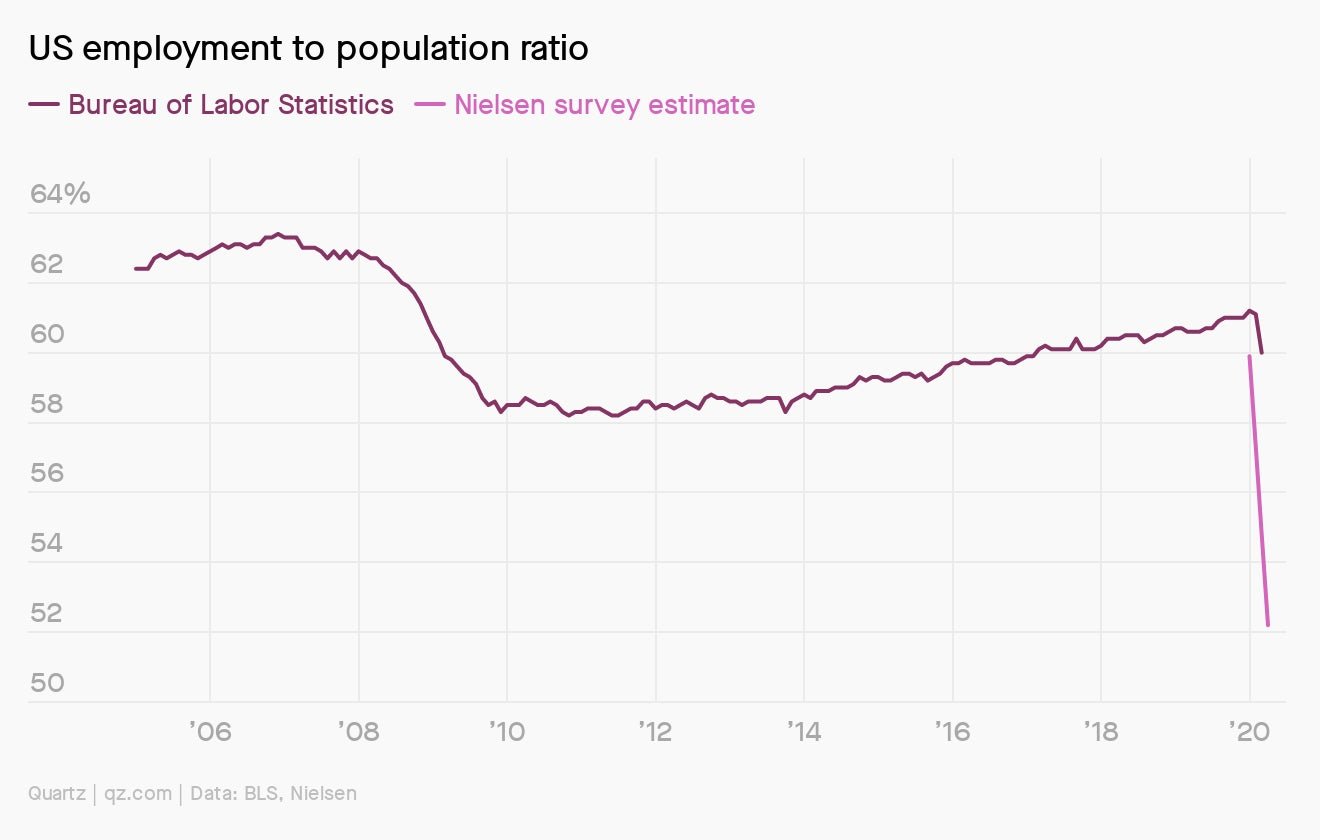

A better figure for monitoring the state of the job market right now is the employment-to-population ratio. This is simply the number of employed people divided by the total population. The study finds that the employment-to-population ratio is likely to fall from 60% in January to 52% in April.

In normal times, this is not the best number to look at because it’s dependent on the age profile of the population. As boomers move into retirement, this number slowly falls. But for this crisis, in the short term, it is a better measure. We will know that the US economy has returned to normality when this number creeps back up to 60%.

On the market

People including the UN’s biodiversity chief and Paul McCartney have criticized “wet markets” as the origin of the novel coronavirus, in some cases calling for their closure. But while many early confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Wuhan, China had exposure to the Huanan seafood wholesale market, Huanan would more appropriately be described as a wildlife market. It had a section that sold wild animals such as live wolf pups, salamanders, civets, and bamboo rats.

Wet market: In Asia —in particular Hong Kong and Singapore—wet markets are akin to large, open-air produce markets, where vegetables and fruits are piled high on crates for shoppers to choose from, cuts of pork and beef hang from hooks, and fish and other seafood swim and float in small tanks or are laid out on beds of ice. Some markets also have live poultry in cages, and butchers only kill and defeather a bird when a shopper decides to buy one.

The often government-regulated markets are “wet” because they don’t primarily sell “dry” goods like packaged noodles, though some wet markets also have stalls selling dry grains and legumes. They’re also “wet” because of the melting ice used to keep seafood fresh, and because shop owners routinely hose down their stalls to keep them clean.

You asked

Where does the six-foot guideline for social distancing come from?

It’s the US Centers for Disease Control that recommends individuals stay at least six feet (two meters) away from one another to help prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. But the CDC isn’t the only word on social distancing. The WHO recommends that people stay at least half that distance apart—three feet, or about the height of a toddler. Meanwhile, an opinion published in late March in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested that people might do well to stay more than 27 feet apart (8.2 meters, or several tall people) to avoid infecting one another.

These conflicting recommendations are understandable, considering that SARS-CoV-2 didn’t exist (to the best of our knowledge) six months ago. Scientists are scrambling to figure out the details of how it spreads from person to person—but there isn’t a single study that can definitively describe all the ways the virus transmits between hosts. For now, the guidelines are based on data collected on other pathogens. The CDC’s guidance supposedly comes from a paper looking at SARS transmission on an airplane in 2003. And the WHO’s three-foot recommendation originates with work done in the 1930s by William Wells, a Harvard researcher who studied tuberculosis. It’s held up for nearly a century.

Follow your cart

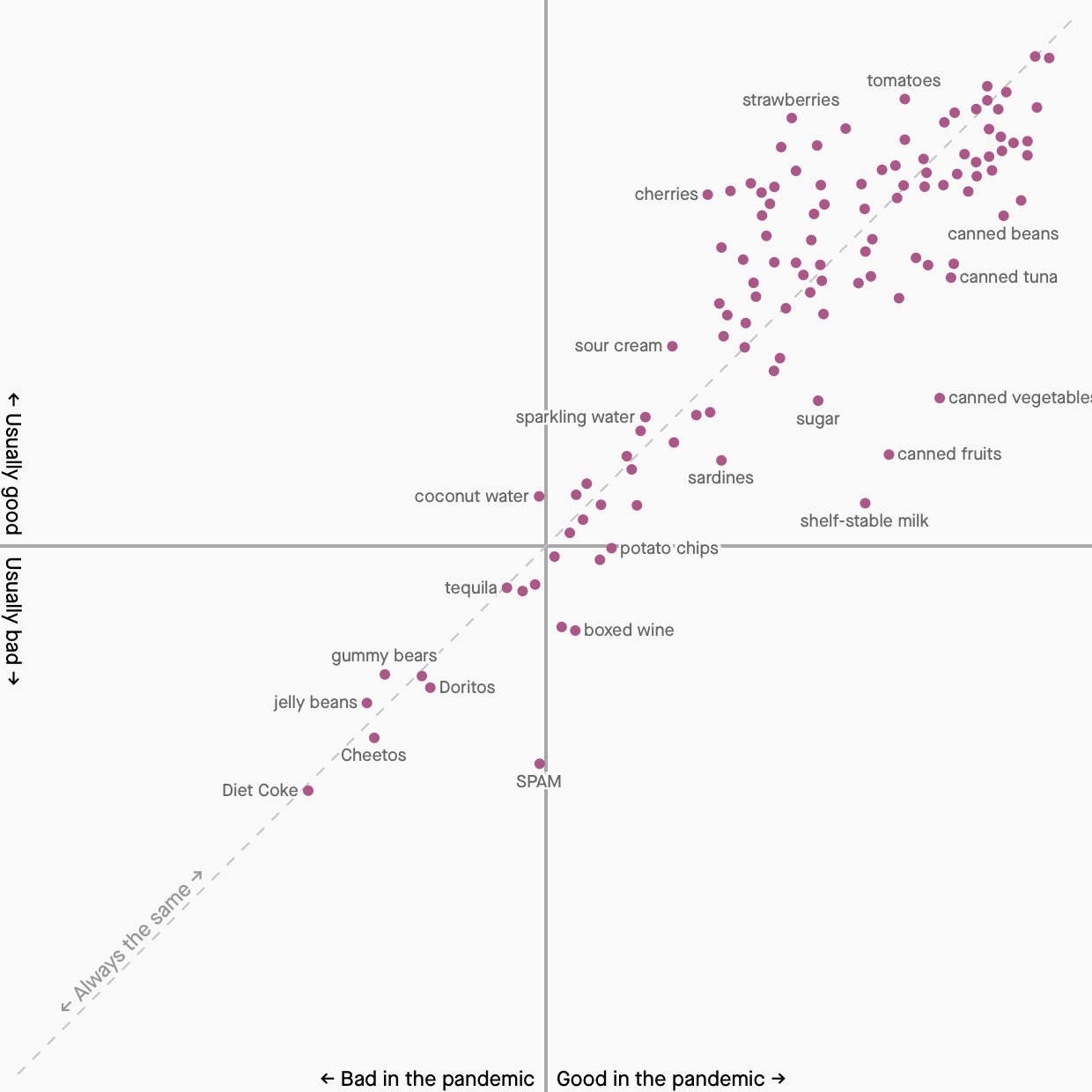

Millions of people around the world are being told to stay home to mitigate the spread of Covid-19. One of the few places people can go is grocery stores. But once you get there, what should you buy?

We’ve been asking readers to help us categorize grocery items by their overall value and their value during a pandemic, in the interest of creating the perfect grocery list—stuff you’d want anyway, but especially right now. So far, staples like eggs, olive oil, and rice are winning out, while canned foods are outperforming. But the big winner is boxed wine.

Join the fun by adding your votes. And if you’re stockpiling something unexpected, ✉️ tell us about it.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 2,766,611 confirmed cases; 760,047 classified as “recovered.”

- On brand: China is using coronavirus to erode Hong Kong’s freedoms.

- Eyes wide shut: How to tackle your Covid insomnia.

- Too soon: Coronavirus is pushing Americans into early retirement.

- Great quarter, guys: Netflix added 15.8 million subscribers in three months.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Dan Kopf, Mary Hui, Katherine Foley, David Yanofsky, Hailey Morey, and Kira Bindrim.