Coronavirus: Worn to run

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

“Social skills are like athletic skills,” says Chris Segrin, a behavioral scientist at the University of Arizona. “If you don’t practice them for a long time, they atrophy.”

Are yours feeling a little rusty? You’re not alone. As we ease back into IRL life, many people are finding interactions with strangers—now marked by an acute awareness of personal space—and hangouts with friends and family harder than they used to be.

But even though it feels like the pandemic has gone on forever, Segrin says it hasn’t been long enough to imprint lasting changes in social behavior. Those kinds of shifts, resulting in completely different social interactions, are more likely observed in wars, where soldiers or prisoners are isolated from their loved ones for years at a time. So hey, silver lining!

Protect your neck

Neck gaiters, buffs—whatever you call them, the jersey-type loops of fabric that can be worn around the neck and over the face and nose—have been a favorite of athletes during the pandemic. Recently, though, major headlines have called the efficacy of neck gaiters into question. Stories in The Washington Post and CNN stated that buffs may actually transmit more droplets than wearing no mask at all.

These stories are reporting research from scientists at Duke University and a local health group called Cover Durham based in North Carolina. The work, published in the journal Science Advances, tested 14 different types of masks, including buffs. It found that neck gaiters made out of a polyester spandex material allowed more droplets of liquid to pass through when the wearer was speaking than any other type of face covering—and even bare lips.

The results sound alarming, and even counterintuitive after months of hearing that cloth face coverings can provide some protection for others during the pandemic. But this study was never intended to evaluate the efficacy of face masks; it was more about designing a new way to test mask efficacy.

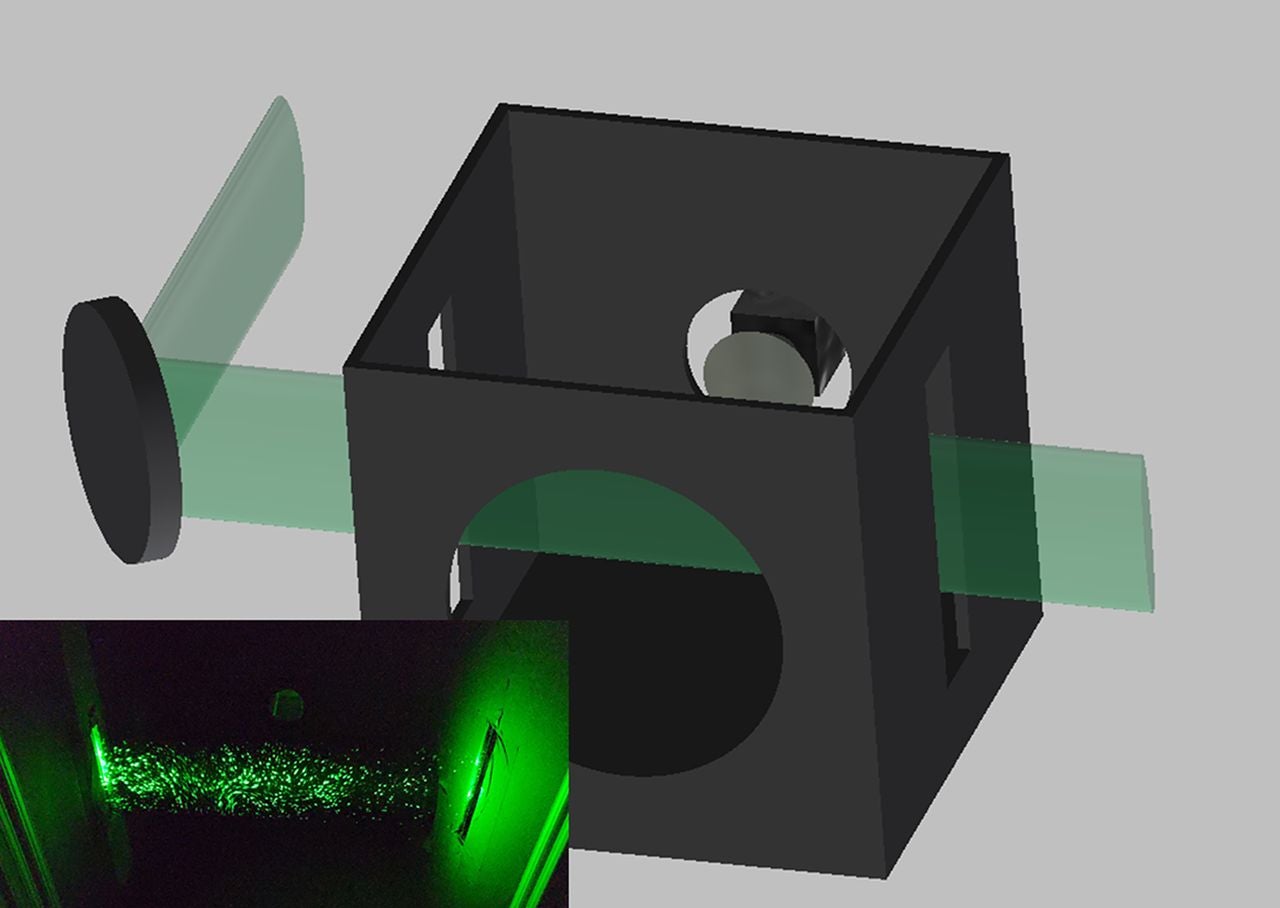

To create a measure of mask efficacy, the team from Duke built a simple system using lasers. First, they beamed a laser through a slit in the side of a box, creating a sheet of light. Through another hole in the box, a person spoke while wearing different types of masks; any droplets that made it through would scatter the sheet of light, which a cell phone camera at the other end of the box could then capture. The contraption looked like this:

The paper was meant to be a proof-of-concept for this new method of testing masks. Currently, groups like the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the European Union have their own standards for testing face masks, but those standards require precise measurements taken in a well-equipped lab.

The Duke team’s approach, while it could be cheaper and easier, is still unproven. “We have not compared our method to other measurement techniques,” Martin Fischer, a chemist and physicist at Duke who led the work, told Quartz.

It’s good to take these kinds of studies as you should all coronavirus news: in the context of all the data scientists have amassed so far. Major public health organizations generally agree that triple-layer cloth masks with some kind of filtration layer and water-repelling properties can protect others from your nose and mouth droplets, and, to a certain extent, you from other people’s droplets. Neck gaiters, while they tend to be just a single layer thick, could protect some droplets from escaping below your mouth. In short, it’s too soon to toss your buff.

Wiping out

The CEO of Clorox says there’s likely to be a shortage of the company’s name-brand disinfectant wipes until 2021. Even though production is up by 40%, the pandemic has increased demand by more than 500%—far more than annual spikes related to flu season.

Fortunately, there are plenty of alternative disinfectants, including ones you can make yourself:

- Start with isopropyl alcohol, hydrogen peroxide, or household bleach. As long as the alcohol is at a concentration of at least 60% or the hydrogen peroxide is at at least 3%, they should be fine on their own. Bleach should be diluted by mixing 4 teaspoons (20 mL) of bleach into a quart (about a liter) of water.

- Use paper towels as wipes; the capillaries in them will soak up whichever solution you use like tree roots taking in water. (Don’t use a washcloth for these solutions, unless you wash between every use. Common cleaners can react to form noxious chemicals.)

- Use an old disinfectant wipe container to store your new wipes. The result should be similar to a traditional Clorox wipe.

One perk of the paper towel fix? These wipes are biodegradable. That can’t be said for traditional disinfectant wipes, which are the main culprits behind “fatbergs,” the massive, disgusting wads of trash and oil that can clog city sewer pipes.

Define your terms

Presenteeism /prɛznˈtiːɪzəm/ (noun) — the practice of being present at one’s place of work for more hours than is required, especially as a manifestation of insecurity about one’s job.

Coronavirus has cast presenteeism in a new light, forcing workers and employers to ask: Should we be preserving a culture that doesn’t benefit most employees or provide an accurate measure of productivity? It’s one of many questions explored in our new field guide to reimagining the office. Here’s what else we look at:

Become a Quartz member to read the full guide, and remember: The office as a place of work isn’t disappearing. Covid-19 just altered our concept of it so drastically that if and when we do return, it might be changed forever.

One quick quiz

1️⃣ Which company wants to turn Sears stores into warehouse space?

2️⃣ What 1960s DIY fashion trend is staging a coronavirus comeback?

3️⃣ Which family member did Vladimir Putin test Russia’s coronavirus vaccine on?

4️⃣ Which pandemic-hit tech startup is planning an IPO this month?

5️⃣ Which frozen foodstuff tested positive for Covid-19 in China?

(answers at the bottom)

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 21 million confirmed cases; 13 million classified as “recovered.”

- Cascading failure: Covid-19 is making the opioid crisis much worse.

- Working from the quad: Remote employees should consider moving to college towns.

- Quick question: Who will get a vaccine first in the US?

- One more: How many tests have African countries done?

- Okay, last one: Will a flu shot protect you from Covid-19?

Answer 🔑

- Amazon. The e-commerce juggernaut has been in talks with Simon Property Group, the largest mall owner in the US, about turning some of the spaces occupied by its anchor department stores into distribution centers.

- Tie-dye. Google searches for “tie dye” usually climb a little in the summer, but they hit their all-time peak this year.

- His daughter. The Russian president said a locally made vaccine was given regulatory approval after less than two months of human testing.

- Airbnb. The home-sharing platform plans to file IPO paperwork later this month, the Wall Street Journal reported. If Airbnb moves forward on that timeline, it could contribute to what’s becoming the best year for IPOs since the dot-com bubble.

- Chicken wings. Two cities in China found traces of the novel coronavirus in imported frozen food and on packaging, raising fears that contaminated food shipments might lead to new outbreaks.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Katherine Foley, Tim McDonnell, Jackie Bischof, and Kira Bindrim.