Coronavirus: Who wants a treatment?

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

Earlier this week, the US Food and Drug Administration gave emergency use authorization (EAU) to convalescent plasma as a therapy for hospitalized Covid-19 patients. If the treatment works, the EAU could save thousands of lives without regulatory red tape.

But without rigorous, controlled testing—which is having trouble getting funded—doctors are still making educated guesses about how exactly to use convalescent plasma. On Friday, The New York Times reported the ouster of two FDA public relations advisers who exaggerated plasma’s benefits for Covid-19.

After you read today’s newsletter (thanks in advance), be sure to dive into Katherine Ellen Foley’s look at what we know so far about convalescent plasma, and just as important, what we don’t.

Let’s get started.

Paging Dr. AI

For years, emergency rooms have haltingly tested artificial intelligence systems that collect information on patients’ symptoms and medical histories, weigh it against data about similar cases, and make recommendations about who should be rushed in for treatment first. Now, the pandemic is dramatically accelerating the use of AI triage.

“The healthcare space is relatively conservative,” says Yonatan Amir, CEO of Israeli health tech firm Diagnostic Robotics. In normal times, it might take six months for Diagnostic Robotics to close a deal with a major hospital interested in its AI triage tools. But in a three-week span between March and April, the company closed over 40 new contracts. In the first five weeks of the pandemic, its algorithms triaged 2.5 million patients.

The change in pace makes sense. “From a safety perspective, you almost had to have some sort of system where you could triage patients before they came in,” says Bill Fera, a medical consultant with Deloitte, which sells AI triage tools and advises health systems on how to use them. Some health systems, including Mayo Clinic, are developing such tools in-house.

AI sellers acknowledge that their machines can make mistakes—but argue that they’ll make fewer than humans might. Fera points to research from Johns Hopkins University that suggests medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the US. “So to the idea that machines are going to come in and do this worse,” he said, “there’s some room for improvement, I’ll put it that way.”

But Daniel Cabrera, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Mayo Clinic, says that AI systems aren’t simply less fallible versions of human doctors. They may never make mistakes due to distraction or exhaustion, but they’ll make other kinds of mistakes that humans wouldn’t.

Cabrera calls these mistakes of context, and cites an exaggerated example to illustrate his point: A patient walks into the ER with a knife sticking out of his chest. His main complaint is a stabbing chest pain. But medical records show he’s also a smoker with a history of high cholesterol. An AI system might infer, based on his symptoms and medical history, that he’s having a heart attack and recommend chest X-rays. A human doctor, on the other hand, would immediately begin treating his stab wound.

Cabrera does say that, correctly used, algorithmic triage can help healthcare workers treat patients faster. He compared a well-run emergency room to a fast-food kitchen or a factory assembly line—the goal is to coordinate a lot of people’s efforts as quickly and smoothly as possible.

It’s a no-grow

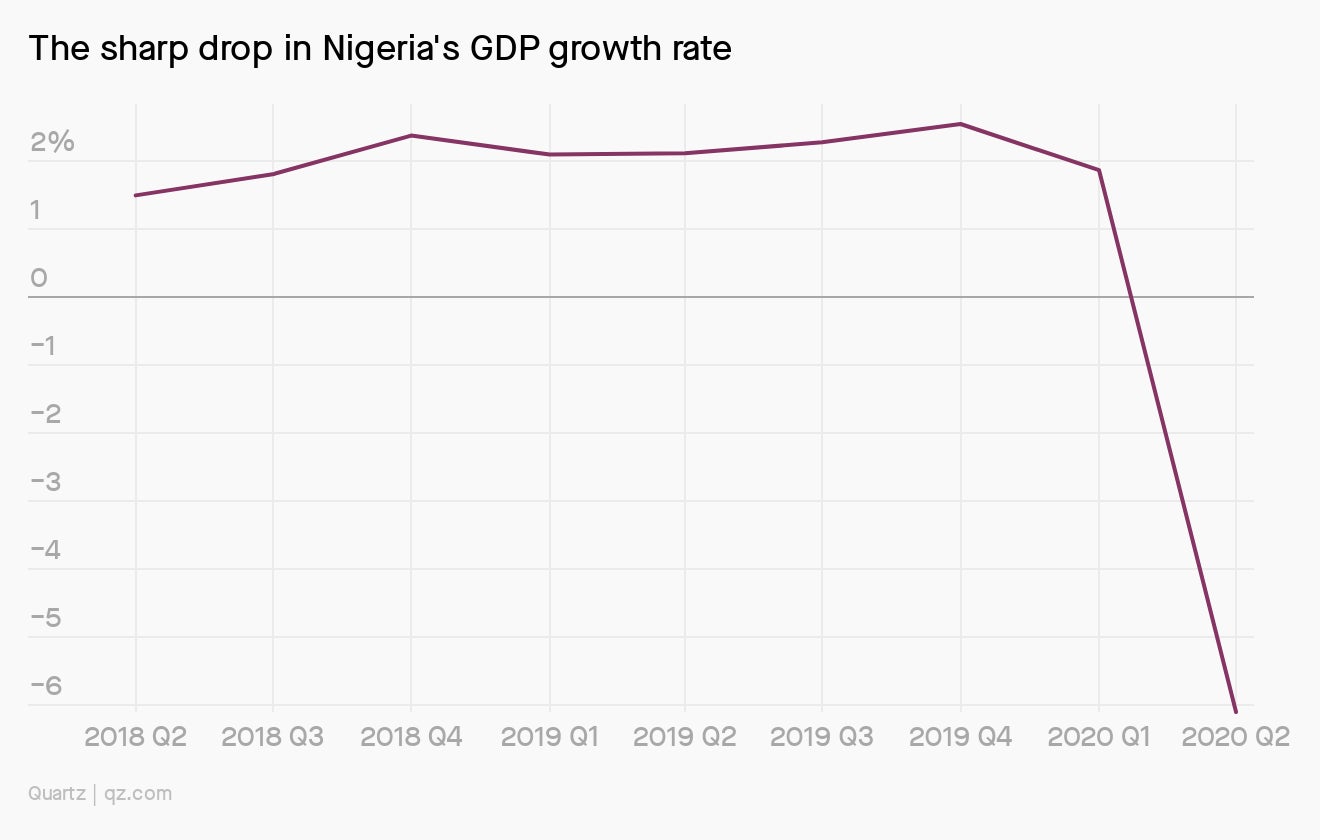

Africa’s largest economy has suffered its worst contraction in more than a decade, with GDP growth dropping by 6.1% in the second quarter compared to the same period a year ago.

As with most other economies around the world, the drop is largely a result of a slowdown in economic activity after the country resorted to a lockdown back in April. While the lockdown has since been eased in the wake of “heavy economic costs,” the continued rise in cases—especially in Lagos, Nigeria’s economic hub—means the local economy is yet to fully reopen.

But Nigeria’s economy has also been crippled by external factors, as the coronavirus pandemic resulted in a near-total shutdown of economic activity around the world. The accompanying steep drop in oil prices amid plunging global demand left Nigeria drastically shorn of earnings given its dependence on the commodity as its biggest revenue source.

You asked

Is coronavirus going to stay with us like the HIV virus?

Yes and no. Experts—including Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—say the ease with which coronavirus is passed from one person to another means that Covid-19 will likely become endemic in society. That’s another way of saying that it’s constantly present in a population at a baseline level, like the flu. In that sense, coronavirus is going to stay with the world more than HIV.

But on an individual level, Covid-19 may be easier to immunize against than HIV. An HIV vaccine has eluded researchers for decades because it’s a particularly wily kind of pathogen called a retrovirus, and theoretically, a coronavirus vaccine could be more straightforward. A vaccine wouldn’t eliminate Covid-19 entirely—we’ve only ever gotten rid of one disease, smallpox, through vaccination, and we’ve been struggling to stamp out polio for decades. But it could be a valuable tool in holding the disease at bay.

Looking for even more You Asked answers? Make sure you’re signed up for the Quartz Daily Brief. It’s, well, daily, which means even more opportunities for us to field your pressing queries.

Deliver us from joblessness

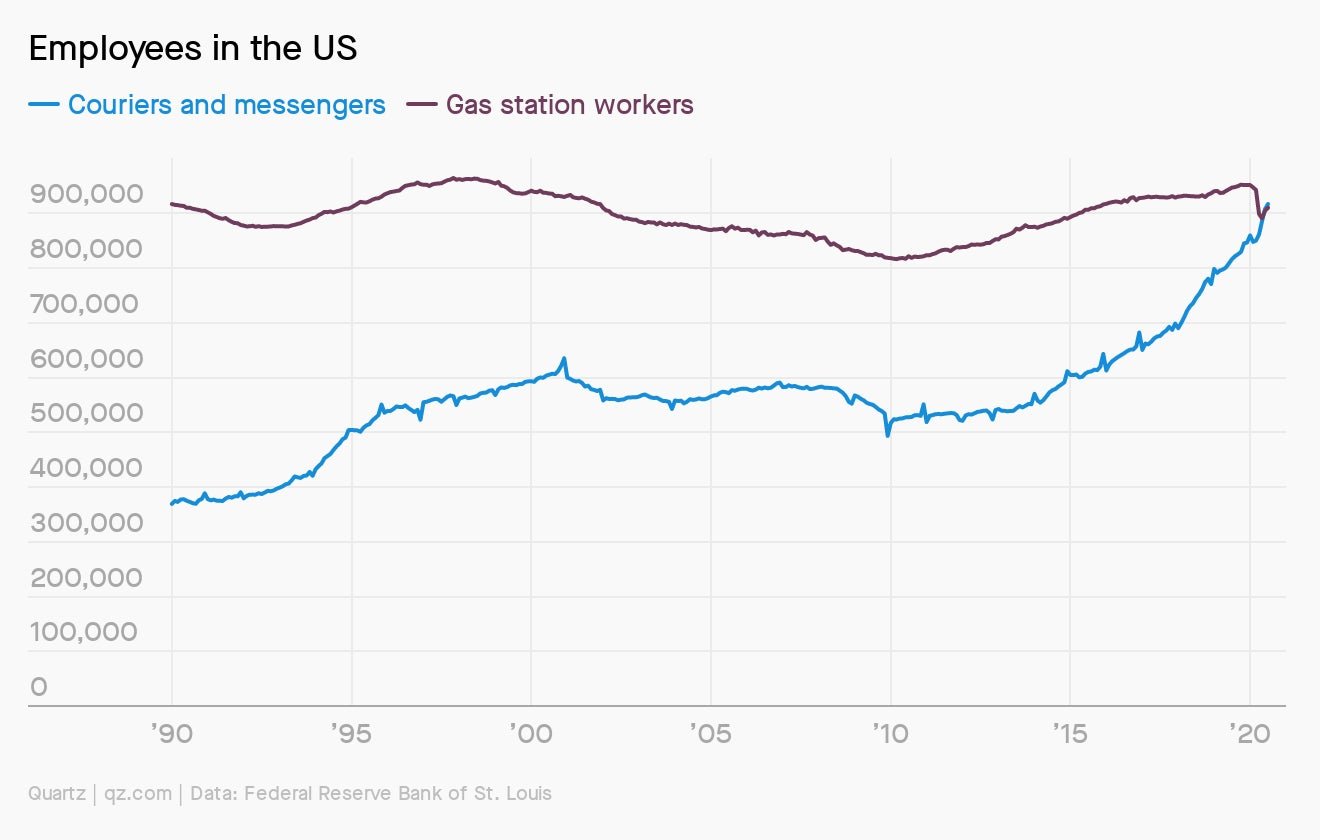

Even before Covid-19, delivery jobs were the fastest growing in the US. The pandemic sent that trend into overdrive. From February to July, the number of people working as “couriers and messengers” jumped from less than 850,000 to almost 920,000, an increase of over 8%. At the same time, overall jobs in the US economy fell by 8%.

With fewer people commuting to work or visiting stores, jobs at gasoline stations also fell 4% over this period. This means July was the first time on record that more people worked in delivery than at gas stations, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Trying long-distance

When companies suddenly moved to remote working, a likely casualty appeared to be corporate culture. But in a new study from Quartz and Qualtrics, 37% of 2,100 respondents said their workplace culture had improved since the start of the pandemic, compared to 15% who said it had deteriorated. The rest reported little change.

The global study gave respondents a list of attributes they might ascribe to their company and asked them to rate whether each one had increased, decreased, or remained unchanged during the pandemic. Many more people reported that positive attributes like supportiveness and kindness had increased than said they had decreased. And while it’s impossible to draw conclusions about people’s reasoning based on quantitative results, there are plenty of indicators as to what might be going better.

- We’re wasting less time.

- There’s been a positive shift in flexibility.

- Even though we’re not seeing our co-workers so much, we’re often seeing more intimately into their lives.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 24.5 million confirmed cases; 16 million classified as “recovered.”

- Making connections: WhatsApp is helping India’s small businesses survive.

- In the air tonight: You don’t need fancy air filter systems to reduce Covid-19 risk.

- Staying local: The depressing new data on foreign populations in countries around the world.

- Unhappy hours: Americans are drinking more alcohol at home.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Katherine Foley, Nicolás Rivero, Yomi Kazeem, Dan Kopf, Cassie Werber, and Kira Bindrim.