Welcome back! If you’re new, sign up here to receive this free email every week.

Hello Quartz readers!

I recently spoke to Robinhood about how the company will make money when it launches in the UK next year. To recap, the Silicon Valley brokerage plans to offer US stock trading to British customers in early 2020.

Robinhood doesn’t charge commissions, so it makes money from interest on uninvested customer money, margin (leverage for trading), and payment for order flow (PFOF). The latter is sometimes controversial: American brokerages like Robinhood, Etrade, and Charles Schwab get paid for selling customer orders to high-frequency-trading firms. These orders to buy and sell typically don’t go on an exchange like Nasdaq or New York Stock Exchange, and instead get filled directly by high-frequency traders.

The regulatory watchdog in London doesn’t like these types of rebates. The Financial Conduct Authority says the practice can create a conflict of interest, impose hidden costs, and distort competition. Put another way, as a UK market structure specialist says, the FCA “loathes” the concept of payment for order flow.

But Robinhood has presented the regulator something unfamiliar. Payment for equity order flow isn’t really a thing in the UK. As Alasdair Haynes, the founder of stock market Aquis Exchange, told me, that’s likely because the UK has a much smaller retail market for stock trading than the US. The London market is dominated by institutional investors who are savvy enough to complain to their brokers if they don’t like the way their orders are being handed.

Institutional stock orders also aren’t as valuable for trading firms to buy. Retail trades are lucrative because regular people are “uninformed” or, as Reuters called it, “dumb money.”

The UK’s financial regulator has mainly been dealing with the rebate issue when it comes to certain types of exchange-traded derivatives, according to Sam Tyfield, a partner in London at law group Vedder Price. He says the watchdog has left itself the option of applying its rules to all regulated instruments.

UK regulators don’t appear to be standing in the way of Robinhood’s launch (the FCA declined to comment), but the reasons why surprised me. It’s probably not because the orders are taking place in the US through Robinhood’s American affiliate, or because the trades involve US stocks. Tyfield says the FCA doesn’t make a distinction between where the trades take place. What matters to officials is where the broker is located and where the customer is located.

The FCA’s April statement offers a clue. The regulator visited a broker who was sending orders to an overseas affiliate (the same setup Robinhood is using) and had this to say:

“In one case, a firm also received payments from its affiliate for directing order flow to it. The firm would do this regardless of the classification of its clients. While these brokers typically cited the expertise of those affiliated entities as best serving their clients, they did not assess the impact on their clients of directing order flow to firms that charge PFOF. As a result, these firms failed to comply with the MiFID II-based requirements on conflicts of interest, best execution and inducements.”

Robinhood says it does things differently. It sends orders to multiple trading firms and gets paid the same no matter which one it goes to:

“We have relationships with a number of market makers in an effort to optimize speed and execution quality. Our routing system automatically sends your order to the market maker among these that’s most likely to give you the best execution, based on historical performance.

“We perform regular, rigorous reviews of the market makers’ execution quality by looking at factors like execution price, speed, and price improvement.”

This suggests that Robinhood has a way of explaining to UK regulators that it provides customers with “best execution,” which is a legal obligation to get the best possible results for clients. Regulators can and do change their minds about things, but this suggests the fintech firm will be able to go live next year and make money in its usual way.

But that may not be the end of the story. If Robinhood gains significant market share, will other brokers in the UK, like Freetrade, Revolut, and Hargreaves Lansdown, feel forced to copy this model? That’s pretty much what has happened in the US, where commissions have evaporated, setting off a price war that pushed TD Ameritrade into the arms of Charles Schwab. “There will absolutely be a resistance to any business which seeks to employ a PFOF-like model to retail equities orders,” Tyfield said.

European regulators may be wary of payment for order flow, but they would love to have a robust retail stock market like in the US. Figuring out what to do about rebates could be the first step.

This week’s top stories

1️⃣ Robinhood pulled its US bank charter application. The move highlights the difficulty of becoming a full-fledged bank in America, which is necessary to get to cheap deposit funding.

2️⃣ Institutional investors are less excited these days about the latest stock picks from Wall Street. Investment banks are supplying them with raw datasets to feed into trading strategies, according to the Financial Times (paywall).

3️⃣ Can a bailed-out traditional UK bank, beset by outages, make a successful, new digital bank? We’ll find out, as Royal Bank of Scotland launches Bó.

4️⃣ Curve says it has 500,000 users, but data from May indicates that only 72,000 of them are active each month, according to Business Insider. The all-your-cards-in-one fintech raised $57 million from venture capital investors in July, according to PitchBook.

5️⃣ China is closing down its peer-to-peer industry, which has been rocked by pyramid schemes and scandals. The country has about 400 such lenders, down from more than 6,000 at the peak.

The future of finance on Quartz

In the past five years, a third of British bank branches have closed, damaging economic prospects for communities that depend on them. Former Barclays CEO Antony Jenkins argues that a better banking model is on the rise.

Installment loans can offer a low cost alternative to credit cards. But some consumers can end up spending more on late fees and higher interest rates after a missed payment.

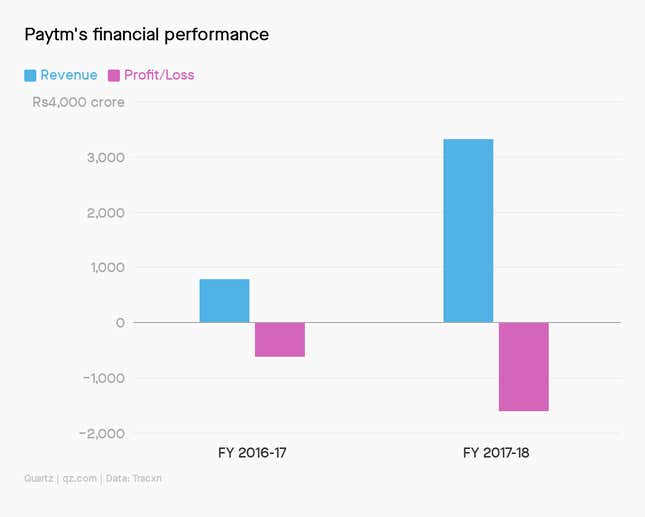

India’s Paytm raised $1 billion to fend off competition from Walmart’s PhonePe and Google Pay. Experts tell Quartz that Paytm’s cash burn is unsustainable.

On Dec. 9, I’ll be publishing a guide to the world’s highest-valued fintech companies. It will include a Q&A with an executive from one of the sector’s heavy hitters, as well as a profile of Nubank, the fast growing digital bank in Brazil. One takeaway is that many of these companies look a lot less like Google and lot more like a plain old financial institutions (which have much lower price-to-earnings ratios than tech firms). Their valuations will eventually have to come to terms with this.

The guide will be exclusive to Quartz members. If you’re not already a member, you can support our journalism and sign up here. Use the promo code JD2912 to get 50% off an annual subscription.

Always be closing

- Ant Financial, which has invested in 160 companies in the past five years, plans to raise a $1 billion fund. It will buy stakes in mobile finance companies in Southeast Asia and India.

- LendingPoint issued two loan securitizations, of $175.7 million and $61.7 million in size. The notes are backed by direct-to-consumer and point-of-sale loans.

- MiddleGame Ventures, an investment firm focused on fintechs, closed a €150 million ($165 million) fund.

- Payment startup Enfuce got €10 million in funding. The company is Finland’s largest fintech.

- Swedish payment and invoicing fintech Klarna says it registered 60,000 new merchants globally this year, a 140% increase from 2018.

I hope your week has been a profitable one (pick your own metric). Please send any stock order rebates, tips, and other ideas to jd@qz.com.