This week in membership: The global fight for Hong Kong

{{section_end}} {{section_start}}

{{section_end}} {{section_start}}

🤔Here’s Why

1️⃣ The fight for the future of Hong Kong has become the world’s fight. 2️⃣ To achieve this, Hong Kongers channeled street protests against encroaching Chinese influence into global politics. 3️⃣ They built connections with politicians in the US and UK, and aligned their advocacy with geopolitical trends. 4️⃣ Despite this momentum and its position as a global financial center, Hong Kong is likely to become a much more Chinese city. 5️⃣ But the identity of Hong Kongers will become more global.

📝 The Details

1️⃣ The fight for the future of Hong Kong has become the world’s fight.

The pro-democracy fight over Hong Kong has evolved at remarkable speed from a local protest movement to a global issue. A national security law, handed down by China on June 30, has pushed discussion of the city’s freedoms into the highest levels of government, and prompted a coordinated international response by some of the world’s most powerful nations.

The territory has been compared to Berlin during the Cold War. At stake is whether Hong Kong goes the way of East Berlin—completely taken over by a Communist dictatorship—or holds out, like West Berlin, as a free, if isolated, enclave in the shadow of an authoritarian power.

2️⃣ To achieve this, Hong Kongers channeled street protests against encroaching Chinese influence into global politics.

In the years since the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement, when protesters occupied major roads to demand freer elections, Hong Kongers have learned to go beyond grabbing international headlines to transform attention from protests into tangible political influence. The dynamic is a symbiotic one: resistance on the ground builds more political momentum, which in turn fuels more protests. Sophisticated and well-connected grassroots lobbying groups, like the Washington-based Hong Kong Democracy Council, used that momentum to successfully push for measures to support Hong Kongers. These include the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which US president Donald Trump signed into law last year.

3️⃣ They built connections with politicians in the US and UK, and aligned their advocacy with geopolitical trends.

In the UK, activists faced an uphill battle with a Brexit government unenthusiastic about immigration, and keen to build closer ties with China. New advocacy groups like Hong Kong Watch and Stand With Hong Kong used both Britain’s colonial past—and a vision of its post-Brexit future—to find allies.

4️⃣ Despite this momentum and its position as a global financial center, Hong Kong is likely to become a much more Chinese city.

Amid the political upheaval, the share price of Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearings has soared, and the company has reclaimed its crown as the most valuable exchange operator in the world by market capitalization. The exchange is a surprise winner from the decoupling between the US and China. That resilience is a sign that China has the wherewithal to resist international pressure, and could undermine one of the key messages of the city’s pro-democracy protesters.

As Beijing’s grip tightens on Hong Kong, it’s clear that the city is running ahead of schedule in becoming less Western and more Chinese. The question is whether its recent success is a fleeting sugar high, and whether deeper structural factors—fewer freedoms and changes to the rule of law—will erode Hong Kong’s financial stature over time.

5️⃣ But the identity of Hong Kongers will become more global.

Many Hong Kongers are forced, once more, to uproot themselves and go elsewhere as their city changes dramatically. They could go to Britain, which has offered millions the right to settle—or Canada, which was transformed by past waves of immigration the 1980s and 1990s, as Beijing cracked down on protesters and the handover loomed.

Many of the places where Hong Kongers will seek refuge this time will come to feel that Hong Kong’s fate is somehow linked to their own.

Last month, the Hong Kong police force put out an arrest warrant for Samuel Chu, the founder of the Hong Kong Democracy Council and an American citizen for 25 years, over his lobbying work, accusing him of “colluding with foreign forces.” Chu’s response to being made an international fugitive to explain, simply and elegantly, in the pages of the New York Times, that if an American citizen lobbying his own government can be targeted by China, then so can anyone. In other words: “We are all Hong Kongers now.”

📚Read the field guide

“We are all Hong Kongers”: How the Hong Kong protest movement became the world’s fight

📣 Sound off

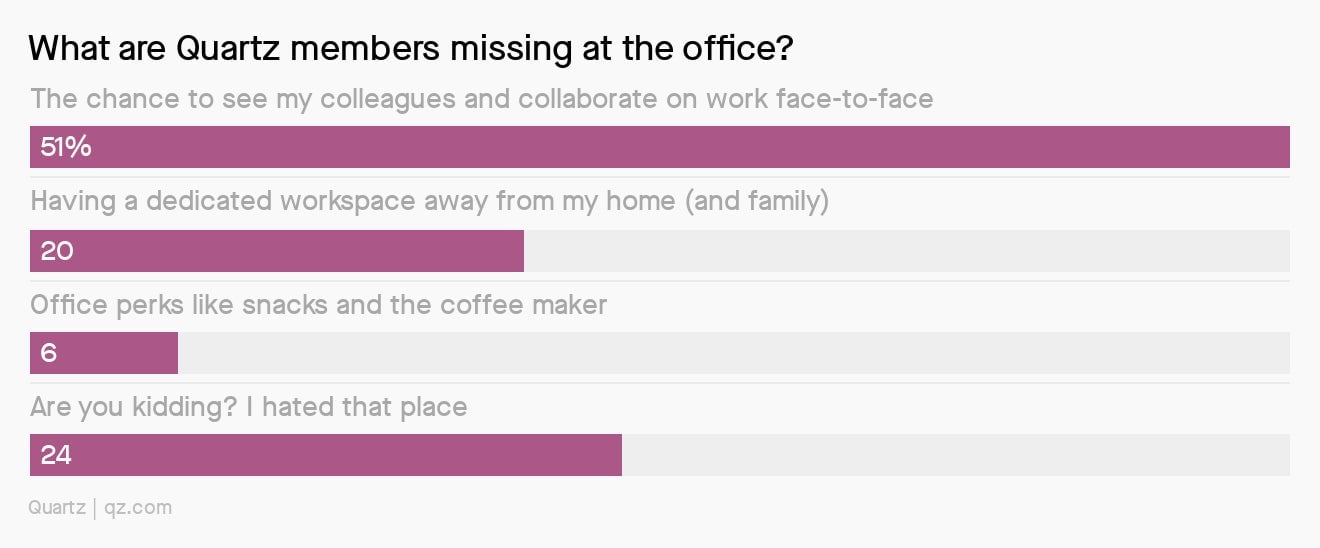

Last week, as part of our field guide to reimagining the office, we asked you what you missed most about it. Here’s what you said: