For Quartz members—The Netflix of podcasts?

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

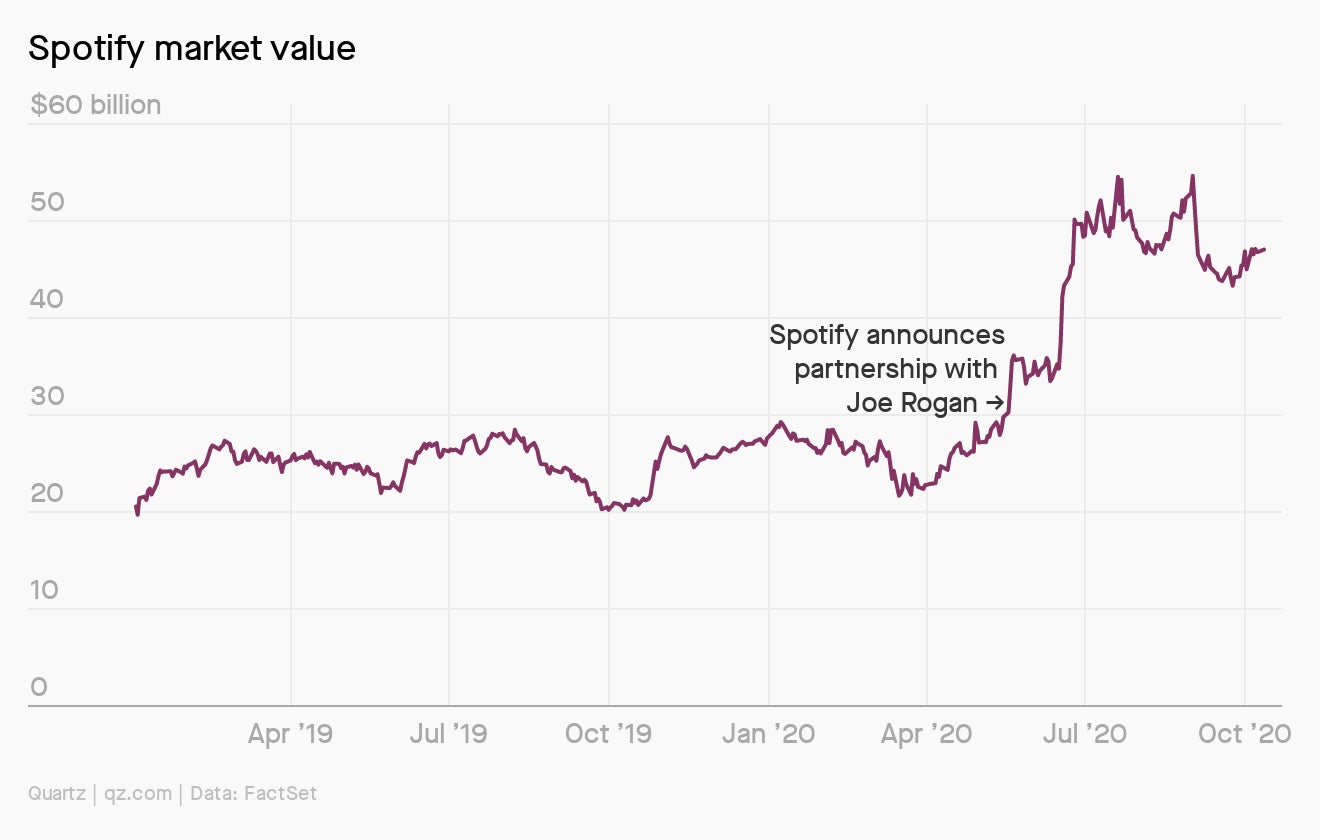

Between April and October, Spotify went from being a $23 billion company to a $47 billion company. What happened? With its financials, not much. The Swedish outfit continues to see steady revenue and user increases, even as it reported losing €355 million ($420 million) in the first half of 2020. But investors have bought into an idea about Spotify: that it could be the Netflix of podcasts.

First, a recap: Coinbase employees are quitting their “apolitical” workplace, Google is facing antitrust drama in India, and Disney is a streaming company now. A youth-led movement is driving protests in Nigeria, and China’s much-hyped digital yuan is here. Are you reading this in sweatpants? We get it. No one wants to wear jeans anymore.

Your most-read story this week: Apple will change the way we charge phones. And most generous and kind-hearted member goes to everyone who takes this three-minute survey to help us understand how you use Quartz. 🙏

Okay, put on your headphones and turn up the volume. We’re spinning Spotify.

The podcast pivot

Historically, Spotify’s problem has been that it sells a commodity. The Swedish company, founded in 2008, primarily serves as a platform for music. Spotify’s users have easy access to a music library that includes nearly everything one might want to listen to. The challenge for Spotify is that basically the same library is available on competitor platforms like Apple Music, YouTube Music, Pandora, and Deezer.

Currently, the main differentiating factors for music streaming platforms are their app features and speed. Spotify has done well in these areas, but if someone decides they like a feature Apple Music developed, there is little to stop them from switching platforms.

Being a commodity provider is also bad for negotiations with suppliers. In this case, music labels like Sony, Universal, and Warner Music know that Spotify needs them more than they need Spotify, since the labels have other options and Spotify does not. This means the labels can push for a larger share of Spotify’s earnings—the company currently gives music labels more than 50% of revenues.

Enter podcasts. In exclusive podcasts, Spotify sees an opportunity to get out of the commodity game. Since the beginning of last year, Spotify has acquired podcasting companies The Ringer and Gimlet Media, and inked exclusive deals for Michelle Obama and Kim Kardashian’s podcasts, as well as the exclusive rights to develop podcasts based on the DC Comics universe. In May, the company made its biggest splash yet with the $100 million acquisition of exclusive rights to popular interview podcast the Joe Rogan Experience, consistently one of the five most popular podcasts in the US.

Spotify’s emphasis on podcasting is, to some degree, already working. The company reported in July that podcast listening on the platform had doubled from the previous year. But with exclusive podcasts, Spotify can also have a truly differentiated product. Users who love their podcasts will have no choice but to subscribe. Analysts say this could even give Spotify more leverage with music labels: With a larger share of dedicated users, the labels might start needing Spotify as much as Spotify needs them.

Another reason for the podcast pivot: Spotify can use them to sell ads. Although subscribers get music ad-free, that’s not the case for podcasts. The company can also use its exclusive podcasts to insert different ads into the same podcast, allowing targeting of users based on demographics (historically, all listeners to a podcast get the same ads).

Spotify’s podcasting gambit makes a ton of sense, and the market is confident it’s a good idea. But it’s a bet that could also go seriously wrong. If Spotify’s podcasting strategy is successful, deep-pocketed competitors like Apple and Google (owner of YouTube Music) should be able to copy it. There’s already a new threat in Amazon, which recently announced that it would heavily invest in podcasting. As it was for Netflix, Spotify will need to take advantage of being the first big mover in the space. That just may not be as easy as it looks.

Is Spotify killing the Top 40?

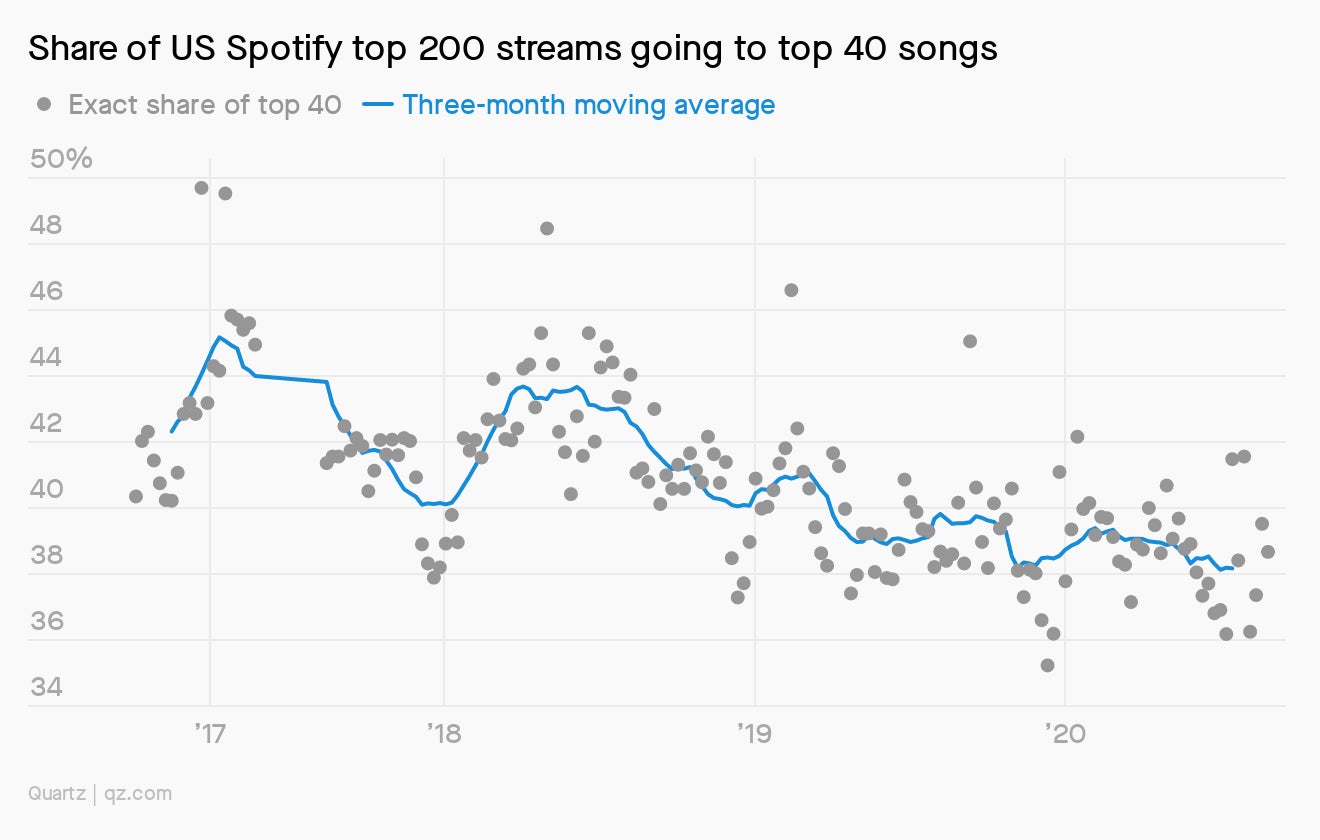

Each week since late 2016, Spotify has shared data on the number of streams for the top 200 songs on its platform. Quartz’s analysis of this data shows that the top 40 songs on Spotify in the US would get a total of around 35 million streams on a typical Wednesday in 2018. In 2020, the 40 biggest hits rarely get 30 million streams. The data show that in the first six months of 2020, the total number of streams for songs 41-200 was almost exactly the same as in 2018. It’s only the top 40 that have fallen.

One possible explanation is changes to Spotify’s app. The streaming giant has increasingly emphasized discovery on its platform, and in its latest quarterly report (pdf) Spotify said that the number of artists making up the top 10% of streams rose by over 40% from 2019 to 2020. In other words, it used to be that a smaller number of artists were concentrated at the top, but now it’s more diffuse.

Europe’s unicorn wants to spawn

When it comes to big tech startups, Europe doesn’t really compare with the US and China. While the US has mega-companies Amazon ($1.72 billion valuation) and Google ($1.07 billion), and China has Alibaba ($822 billion) and Tencent ($684 million), no European company has reached those heights. With its nearly $50 billion valuation, Spotify is as close as it gets.

Spotify founder and CEO Daniel Ek thinks it doesn’t have to be that way. Ek announced in September that he will invest €1 billion ($1.18 billion) over the next decade in tech “moonshots.” In announcing his investment at the Slush conference in Helsinki, Ek proclaimed the continent had more than enough talent to compete. The problem was in funding and culture. (Ek is worth about $3.8 billion, according to the Financial Times.)

“Despite the ingredients we already have here in Europe, we are still not realizing our full potential,” Ek said. “Our thinking can be too short-term, and we tend to be hesitant to take the risks involved in sticking it out on our own and embracing the unknown.”

The TikTok Connection

From Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” to “Roxanne” by Arizona Zervas, some of today’s biggest hits first blew up on TikTok. Songs become popular on the short-form video app through dance challenges, but they don’t just stay there. After hearing the snippet of a song in a video, many listeners will switch over to Spotify to listen to the full version. The TikTok to Spotify connection has created many a surprise hit:

“SUPALONELY,” by BENEE. Five months after the release of this song in September 2019, it was getting little play. Then a dance challenge caught fire on TikTok: Eventually, more than 10 million videos of people dancing to “SUPALONELY” were uploaded to the app. From there, it jumped to Spotify, where it exploded from outside of Spotify’s global top 200 songs on March 3 to a top 20 song by March 23, all without the help of radio play. The song has now been streamed almost 440 million times on Spotify alone.

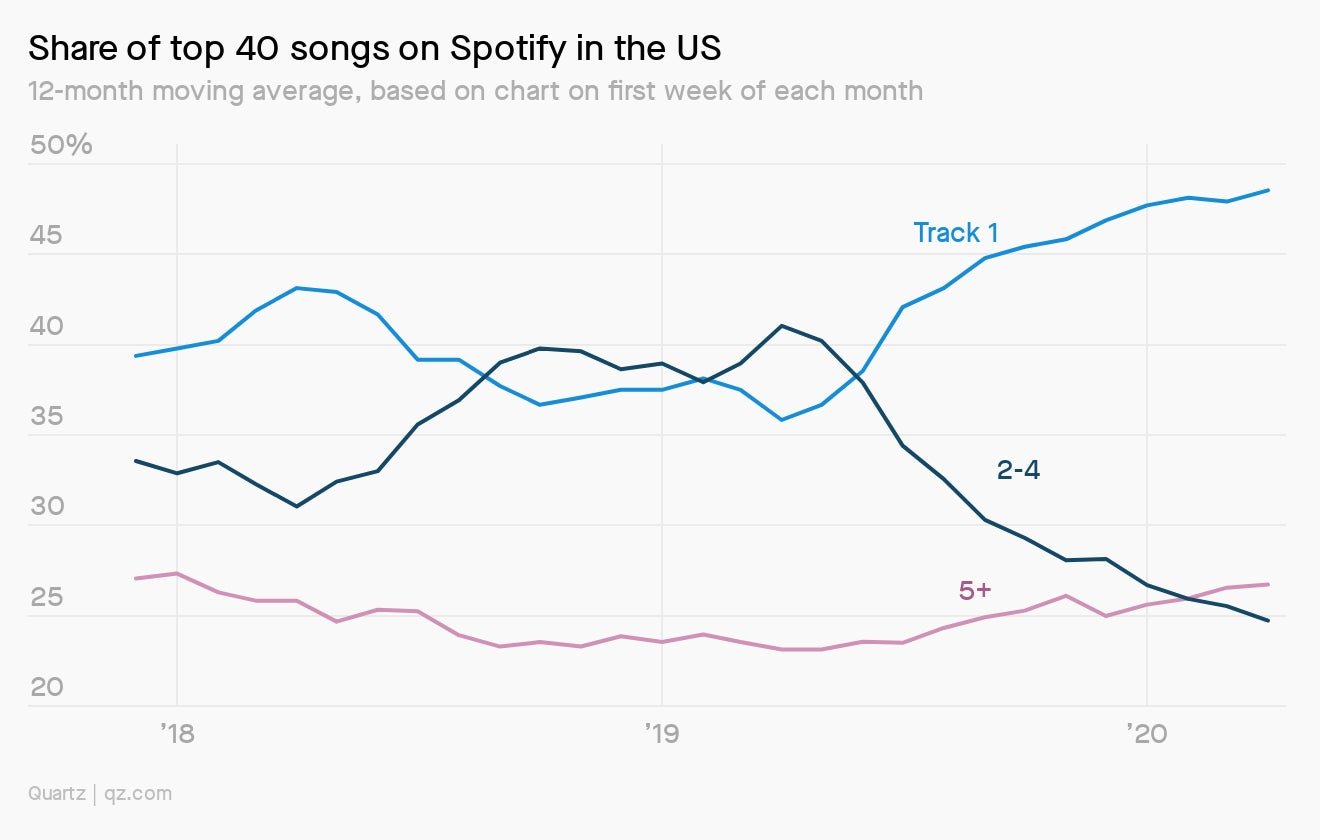

TikTok might also be helping kill the album. A Quartz analysis of Spotify data shows an increasing number of the top 40 songs in the US are the first track of a music release, and suggests a significant share of these songs are single-song releases that exploded on TikTok.

Keep reading:

- Many Spotify employees are not happy about their company’s relationship with the controversial Joe Rogan. Dylan Smith in Digital Music News explains the kerfuffle.

- We have entered the era of Spotify SEO. As Peter Slattery outlines for OneZero, artists with search-optimized names like “Stress Relief Music” and “Relaxing Music Therapy” have emerged to grab streams from users seeking a specific mood.

- The 2019 book Spotify Teardown, written by a group of Swedish media studies professors, historians, and programmers, asserts Spotify initially relied on piracy to get off the ground, and argues through historical records that the company’s contention that it was founded to help people “discover better music” is a sham.

- Alex Ross writes in the New Yorker about the harsh environmental impact of streaming music.

- Spotify’s rules incentivize shorter songs and allow super-users to have an outsized impact on who gets paid, according to, well, us.

- Quartz’s forthcoming field guide to podcasts, and how Spotify is turning them into a data business. The guide will hit your inbox on Monday.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a Top 40 end to your week,