De La Rue: Currency printer to the world

The world’s largest money printer made bank during the pandemic.

The moneymaker

Suggested Reading

On the outskirts of the English town of Basingstoke, a building combines the beige sprawl of the McMansion and the ceremonial driveway of the English manor. It looks innocuous, but security is tight. Visitors cannot be left alone for even an instant. Swipe-card access is everywhere.

Related Content

De La Rue, the building’s occupant, is in the high-stakes business of authentication. It designs and prints national passports, as well as the silver foil labels that mark cigarette packs and alcohol bottles as genuine. Most crucially, it works with roughly half of the world’s central banks on their currency notes: designing them, developing security features to protect them from counterfeiting, and printing them. From its presses in Asia and Europe, De La Rue turns out up to 6 billion banknotes a year, making it the world’s largest commercial printer of currency.

That number is only a fraction of all the notes printed worldwide annually. The biggest central banks—such as those of the US, China, India, and Brazil—tend to have their own presses. Still, many smaller countries outsource their production of money. De La Rue prints British pounds, Fijian and Barbadian dollars, Qatari riyals, Sri Lankan rupees, and dozens more currencies.

How did a 200-year-old company, which got its start in playing cards, wind up supplying the world with currency? Forge ahead to find out.

By the digits

169: Currency issuing authorities in the world

80-90: Issuing authorities, out of the 169, that De La Rue works with currently, whether to supply designs, security features, banknote material, or fully finished currency notes

170 billion: Banknotes issued every year around the world, as a rough estimate

18-20 billion: Banknotes printed by private companies like De La Rue, rather than by national currency presses

Up to 6 billion: Banknotes that De La Rue, the largest of the commercial printers, prints every year

35-45 million: Banknotes that De La Rue’s facility in Malta—its largest—can print every week

All digits provided by De La Rue.

Take me down this 🐰 hole!

Noteworthy events

A major issuer like the Bank of England will place a currency order annually; smaller banks can order once every few years. But the past is not always a reliable guide. During times of inflation, for instance, the demand for notes grows. De La Rue is one of the few companies for which inflation—or, for that matter, regime change—is a good thing. The fall of Saddam Hussein warranted new notes; so did the creation of South Sudan.

Most countries are better prepared for more predictable cycles of cash use. Around the Middle East, central banks arrange to have more currency on hand before Eid al-Fitr, when it’s customary not only to spend money on festivities but also to hand out gifts of crisp new notes. The same goes for the Chinese New Year and Christmas.

The pandemic proved to be unexpectedly disruptive. A casual observer may have expected cash use to plunge in 2020, as people stayed home during lockdowns and worried about catching the virus from banknotes. In fact, disasters tend to drive people toward cash, as a physical store of safety and wealth. As a result, in most countries, the average value of notes drawn from ATMs went up by about 25-30%. Central banks also wanted new, cleaner notes, and larger stocks of notes in general, so they ordered more.

Across the US and Eurozone, total currency in circulation in September 2020 was more than 10% higher than the previous year. In the US, the number of notes circulating usually tends to rise by an annual 1-2 billion. In 2020, that figure surged to 6 billion.

De La Rue welcomed the bonanza. It had suffered a setback in 2019, when it failed to win a £490 million contract to print the new, post-Brexit British passport. (Ironically, the job went to an EU company). But after the pandemic glut of orders for new notes, demand sank to lower-than-normal levels between 2021 and 2022. The currency division’s revenues fell 2.1%, to £280.9 million. The chair of De La Rue’s board resigned in April 2023 after the company put out a profit warning—its third in a year (a new chair was appointed in May). For De La Rue, the hangover from the pandemic has been more challenging than the pandemic itself.

Brief history

1793: Born on the British island of Guernsey, Thomas de la Rue belongs to a family of Huguenots who have fled persecution in France.

1813: As a 20-year-old, having trained as a printer and publisher, Thomas de la Rue puts out a Guernsey newspaper in both English and French.

1831: After moving to London, de la Rue applies for and wins a patent to print playing cards.

1855: The British government commissions him to print stamps for territories such as the Bahamas, Trinidad, Western Australia, and Ceylon.

1860: De la Rue prints his first currency: £5, £1, and 10-shilling notes for Mauritius. As the company signs up more currency customers—British pounds for a brief period in 1914; China in 1930; a slew of post-colonial states after the second World War—its other business concerns diminish.

1947: De La Rue lists on the London Stock Exchange.

1995: De La Rue buys Portals, a company that has manufactured banknote paper for the Bank of England since the early 18th century.

2003: De La Rue wins the contract to print the Bank of England’s pound notes.

Explain it like I’m 5

The ins and outs of currency design

The most secure place on De La Rue’s campus is the design lab, which has a test printing facility attached. In theory, with unhindered access to these rooms, a skilled operative would be able to print money. Visitors need swipe cards and a unique code to punch in at a revolving door. Everybody leaves personal phones outside; work phones and laptops have their cameras disabled.

It takes around 16 months, on average, to go from initial idea to a final proof of a currency note—which includes not just the design but also myriad security features. Portraits of national eminences have to be sketched carefully, at four times their final size, then reduced to be printed via an intaglio process, which gives it a raised, ridged finish that can be felt with the fingertips. Designers sometimes have to work novel concepts into their notes. When the Maldives held a painting contest to decide the background images on their new banknotes, De La Rue had to figure out how to print the watercolor finish of the winning entries onto banknote paper.

Sourcing images isn’t always easy. Once, for a commemorative $50 bill, Fiji’s central bank staff helpfully took a group photograph of their children, to print on the note. But sometimes the reference material doesn’t include images, so De La Rue has to improvise. At least once, some of the company’s employees have donned period clothing or sports uniforms, to be photographed for a banknote as part of a small scene that needed to be recreated.

Pop quiz

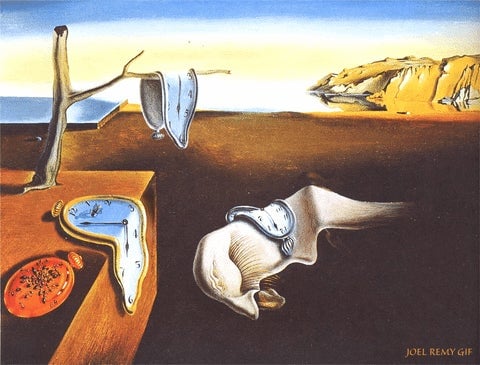

De La Rue uses a bespoke Photoshop plugin for currency design. Which artist is the plugin named for, in reference to his detailed, multi-textured prints?

A. Rembrandt

B. Albrecht Dürer

C. Leonardo da Vinci

D. Salvador Dalí

You’ll find the answer at the bottom of this email, under a pile of British pounds.

One 💵 thing

Coin toss

Unless physical currency disappears altogether, the future seems to belong more to the banknote than the coin. Disks of metal embossed with symbols? How medieval. Coins are more trouble than they’re worth. It now costs 2.72 US cents to make a one-cent coin. Carrying these jangling tokens around is not only cumbersome but, in this age of inflation, also futile. When was the last time a nickel bought you anything?

To gauge the impending demise of the coin, look to the wallet. Gary Bothomley, who co-founded the leather accessories firm Jekyll & Hide, has always hated the coin pocket, the way it bulges and pulls the wallet apart. Half a decade or so ago, 18 out of Jekyll & Hide’s 20 wallets came with coin purses; today, it’s probably three or four. (In countries where parking meters take only coins, wallets with coin pockets do well). Dilip Kapur, who founded the Indian firm Hidesign, suspects that fewer than 10% of the wallets he sells have coin holders. “In fact, I can’t remember the last time we designed a new wallet style with a coin purse,” he said. “My gut feel about coins is that I’m not designing for them any more. I can’t see a market for them.”

Poll

Which are the best looking among De La Rue’s banknotes?

- Barbados’s multicolored dollar bills

- The Maldives’ watercolor-finish rufiyaa notes

- Qatar’s seven denominations of riyal notes

- The UK’s new notes featuring King Charles III

Cast your vote—it costs you nothing!

💬 Let’s talk!

In last week’s poll on target-date funds, 44% of you said you wish your retirement savings actually gave you the ability to time travel so you can retire now; 27% of you want invisibility; 17% of you want to control the weather; and 12% of you said you wish your retirement savings came with a side of telekinesis.

Today’s email was written by Samanth Subramanian (who hasn’t used a physical banknote in months and months) and edited and produced by Annaliese Griffin (uses cash at small businesses, while passing along card fees to corporations).

The correct answer is B., Albrecht Dürer, whose woodcuts featured the same complex line designs that we see in many currency notes today.