The immigrants' World Cup

One in six players at the FIFA World Cup are representing countries other than the ones in which they were born

Hi Quartz members,

In the 13th match of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, the Swiss striker Breel Embolo gently held his hands up after scoring the winning goal against Cameroon. Stopping himself from celebrating was a sign of respect: He had just scored his first-ever World Cup goal against the country where he was born, and where his father still lives.

The World Cup arrived in a haze of immigration-related scandal. Qatar’s stadiums and infrastructure have all been constructed by migrants, most of them from poorer Asian countries. Around 400 of these workers died on site, a Qatar official admitted. It didn’t come as a surprise; many Middle Eastern countries are case studies in the seamy realities of migrant labor: poor compensation, dangerous working conditions, mistreatment of workers.

But there are many other migrant workers at the World Cup who reveal an alternative model for immigration and globalization. Like Embolo, they’re on the pitch, playing soccer.

Embolo is one of 136 soccer players at Qatar representing countries other than the ones in which they were born. Those 136 form 16% of all the squad players at the tournament—an astonishing one in six. The nations in the Middle East aside, not many other countries anywhere would be able to point to migrants forming 16% of the workforce. In Canada, for instance, recent immigrants make up 8% of the labor pool; in Japan, foreigners comprise just 2.5% of the working population.

Soccer, then, is a different kind of country—one with more cosmopolitanism, more mobility, and fewer obstacles for talent. Very different from the kind of labor market that hosts the workers in Qatar who built the Lusail Stadium, maintain its grass, and clean up after its games.

THE PASSPORT OF SOCCER

FIFA, global soccer’s governing body, revised its eligibility rules in 2020 to insist that players must have “a genuine link” with national teams they intend to play for. The basic criteria are: place of birth, naturalization by residence, or place of one grandparent’s birth. But the rules contain exceptions for complex cases like stateless people.

One of the rules’ aims is to stop “nationality shopping,” where soccer associations seek out players who have been overlooked in their home countries. An infamous example was Qatar’s attempt to woo three Brazilian players in 2005, allegedly with cash inducements of up to $1 million.

Foiled by FIFA, Qatar chose a different route to build its national team: scouting pre- and early teens from elsewhere and training them at the sprawling Aspire Academy in Doha. It is no surprise that Qatar’s squad at this World Cup has 10 foreign-born players from eight different countries.

IMMIGRANT SONG

FRANCOPHONIE

Morocco is the only squad in the tournament with more than half of its 26 players born in other countries. Senegal, Tunisia, and Cameroon also have a slew of foreign-born players. What gives?

Behind this, it turns out, is nothing less than the history of European imperialism.

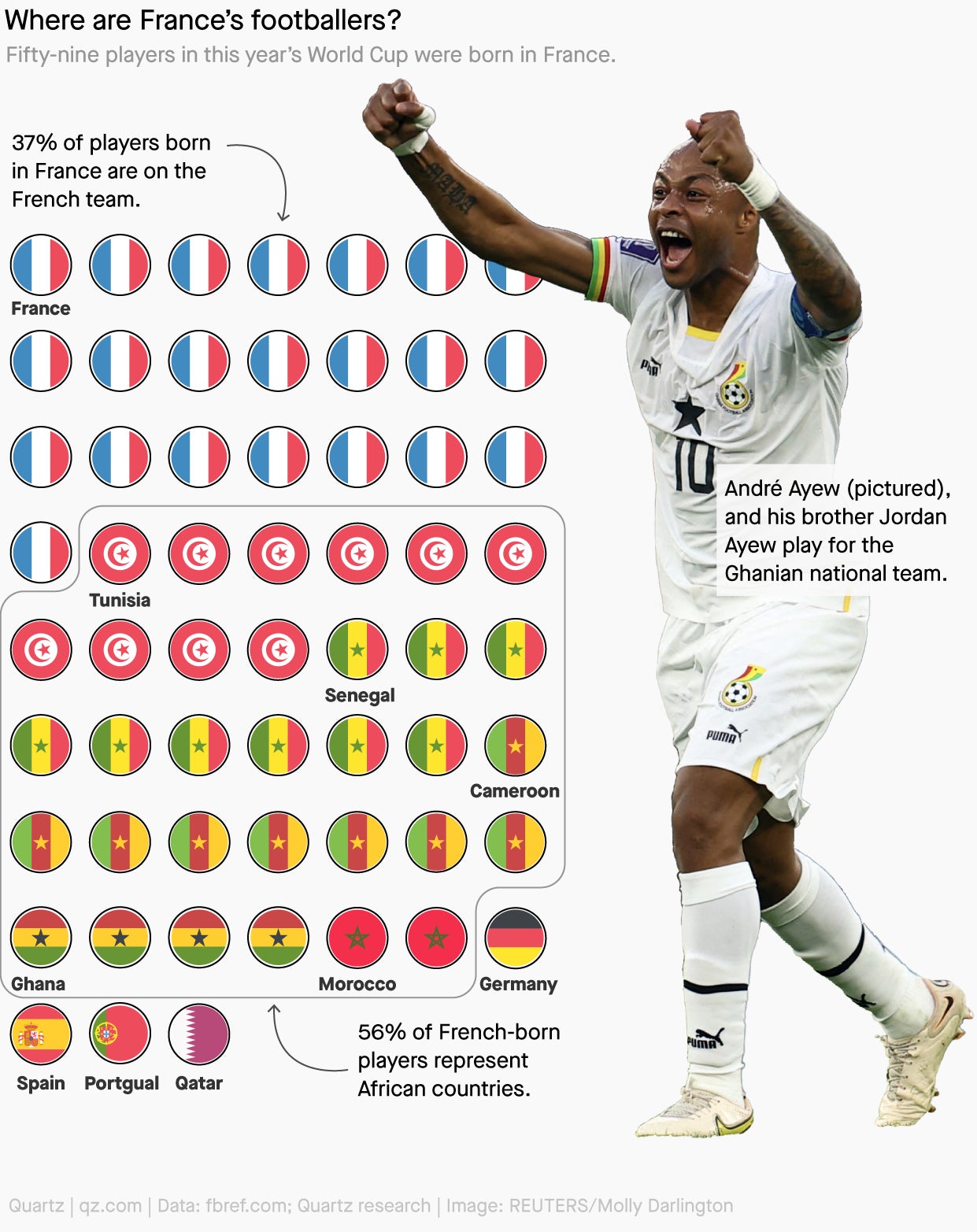

These four countries have heavy French-born contingents in their squads. They’re all erstwhile French colonies. Their citizens speak French, and they have strong cultural and trade ties to France. Naturally, people from these countries migrate to France often, and go on to establish families there.

France and other European countries like Belgium and the Netherlands have well-structured soccer academies and clubs, of the kind often missing in Africa. The children of African migrants there pass through the system to become soccer players. But the competition at the very top is fierce. While some players of African descent like Bukayo Saka and Antonio Rüdiger have gone on to play for the European countries of their birth, many more become available to play for African teams even after representing their European homes at younger age grades.

African teams haven’t been shy to take advantage of this external reserve of talent. One notable move ahead of this World Cup was Ghana convincing 28-year-old Spanish-born player Iñaki Williams to turn out for the Black Stars, even as his much younger brother Nico was called up for Spain. (Ghana did something similar with two of the Boateng brothers in 2010.)

And so it is that 42% of Africa’s 130 players at Qatar were born outside the continent, mostly in France. Of the 59 French-born players in this World Cup, more than half represent African teams. At a time when Africa’s governments want to loosen colonial structures binding them to France—the CFA monetary system and military deployment, to name two—this import of soccer talent may not wane anytime soon.

ONE ⚽ THING

Behind every successful team—or unsuccessful one, for that matter—is a manager-coach. These gentlemen, too, are frequently imports, so we ran the numbers for them as well. Of the 32 teams, 13 have foreign-born coaches. At 40%, that is an even higher proportion of foreign-born talent than the 16% for the players.

One detail stands out. Of the four squads to include no foreign-born players at all—Brazil, Argentina, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia—two have foreign-born coaches. Saudi Arabia picked the French-born Hervé Renard to guide the team, and South Korea hired the Portuguese Paulo Bento. Both South Korea and Saudi Arabia are footballing nations on the rise. Brazil and Argentina, on the other hand, are historic soccer powerhouses; they have plenty of homegrown expertise to choose from. For better or for worse, their teams are wholly local, through and through.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Elon Musk is a bad spokesman for a good fight against app store monopolies

- How companies can move from playing ESG defense to ESG offense

- Sam Bankman-Fried’s first public appearance since FTX collapsed

- Russian industries, hit by sanctions, are now shopping in India

- The auction of 100 untouched Indonesian islands offers a unique chance to the super-rich

- Actually, most people like their bosses

- There’s hope for the Fed’s “soft landing” but economists are nervous

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

⚽ Totaalvoetbal. In the early 1970s, the Dutch introduced a style of play in soccer called “total football.” Embodied by superstar Johan Cruyff, the aggressive and semi-chaotic tactical system reached its heyday at the 1974 World Cup. In a piece for GQ, Rosecrans Baldwin considers what lessons the bygone strategy has taught him off the field, and remembers his late friend Lars, a soccer devotee who taught him to love the sport, and the Oranje.

🐧 Pay the penguins! When it comes to marketing, a host of different critters are deployed to entice consumers. The problem is, according to some, those animals aren’t getting their dues. Enter the Lion’s Share Fund, a project created so that companies using animals in branding, such as Frito-Lay’s Chester Cheetah, can chip in towards wildlife protection. Undark reports that Gucci and Cartier are participants, but not everyone’s on board Noah’s donation ark.

🍒 A bet and a bribe. The UK is the largest regulated gambling market in the world. The development of the digital casino space, where every smartphone can become a slot machine or a card table, has generated billions of pounds, but has also created mass addiction issues. A story from Bloomberg looks at how the gambling lobby has lined Westminster’s pockets, oiling the levers of the great betting machine, while also resulting in deadly consequences.

🐋 A whale of a mystery. Blue whales, the world’s largest and loudest mammals, are singing deeper than before. Nobody knows why. Nautilus provides us with a whale recording (sped up so it’s audible to us humans) and an outline of the mysterious 40-year decline in frequency. Scientists have a theory that population growth may be impacting their songs, but the numbers don’t really add up. Even curiouser, other species of whales have been changing their tune, too.

🏡 Little lessons. In recent years, there’s been a revival of the historied art of miniatures. It’s Nice That speaks to several tiny replica makers about their styles, motivations, and philosophies, seeking to shake up the common perception that it’s just a quaint hobby. Whether it’s Laura Woodroffe’s room portraits or Mahnaz Miryani’s veggie verisimilitude, the accompanying photo essay shows that the artistic medium requires a meticulous hand and discerning eye.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Kick the ball around this weekend,

— Alexander Onukwue, West Africa correspondent; Amanda Shendruk, senior reporter; Samanth Subramanian, global news editor.

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck