The bare medicine shelf

Why have US drug shortages have reached an all-time high?

Hi, Quartz members!

Suggested Reading

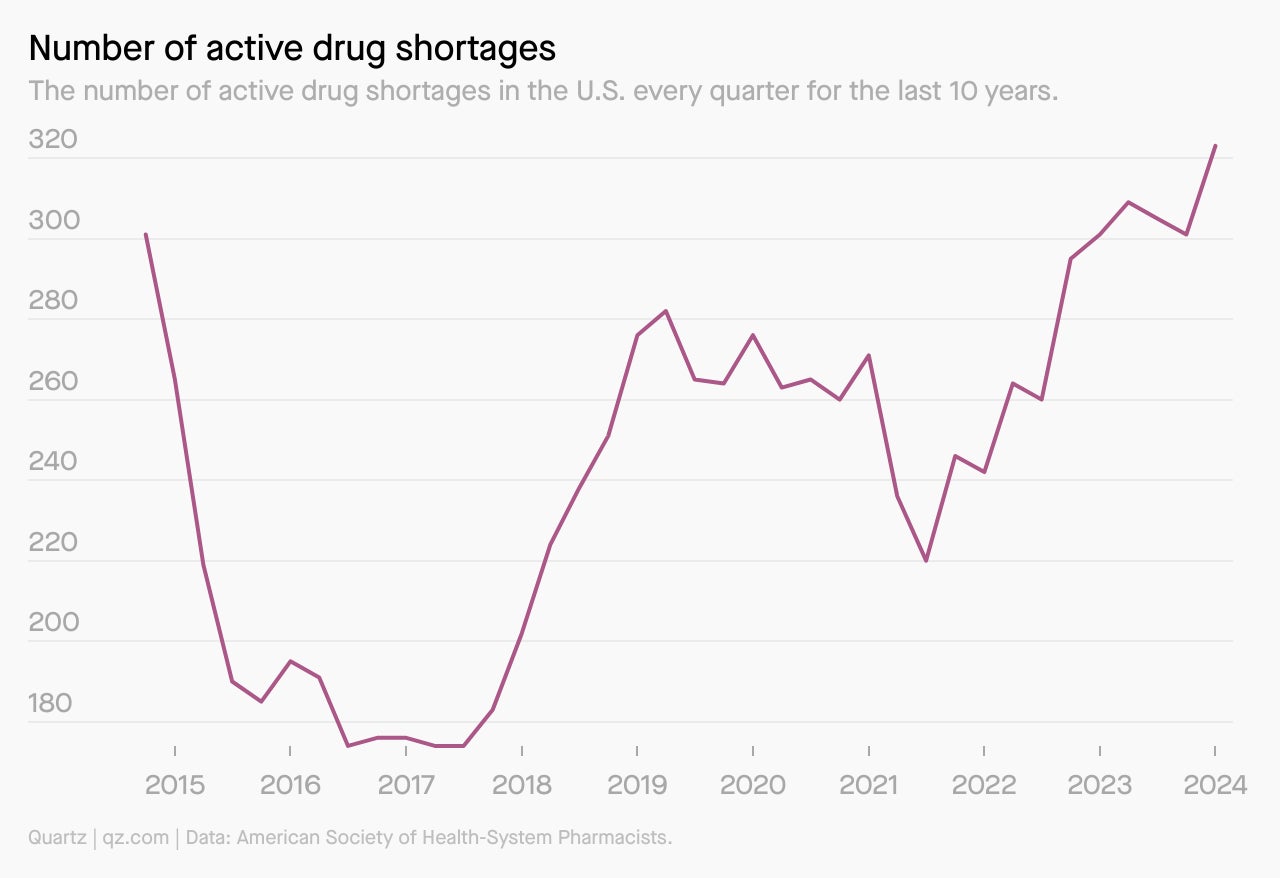

On the last day of March, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) has added 48 new drugs to its tracker of national shortages. Which brought the total number of drugs on that tracker to 323 — the highest since the society began keeping count in 2001, as Quartz’s Bruce Gil pointed out.

Related Content

The medicines in short supply range all over the breadth of human ailments. They include the kind of ADHD drugs that people take daily. They include pain and sedation medicines, and oxytocin, antibiotics like amoxicillin, and chemotherapy drugs. The top five classes of drugs affected are central nervous system medications, antimicrobials, hormone agents, chemotherapies, and fluids and electrolytes. Nearly half of the drugs (46%) in limited supply are injectables.

For healthcare, this is a huge challenge. It isn’t necessarily easy to switch from an unavailable drug to an available one, because the impact or side effects may vary. As a result, doctors are having to think hard about when and whether to start treatment with a drug in short supply. “Is there a curative intent? Is there a chance that we’ll cure that cancer? Or are we doing something to try to prolong their overall survival?” Michael Ganio, a senior director at ASHP, told PBS. All these questions, Ganio said, “may play into which patients get the drug and which ones don’t.” Hospitals spend at least $600 million a year managing shortages.

How did this dire situation come to pass?

CHARTED

BY THE NUMBERS

Last year, the University of Utah Drug Information Service asked manufacturers for the reasons behind the drug shortages. Their responses shook out as follows:

60%: Would not provide reasons, or said they did not know

14%: Cited a supply-demand issue

12%: Cited a manufacturing issue

12%: Cited a “business decision”

2%: Cited problems with raw materials

THE QUOTA SYSTEM

The ASHP said that the shortages of 12% of the drugs on its tracker are being partly exacerbated by quota changes at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

In August, the agency changed the process for manufacturers to receive their limit or quota allotment for how much they can produce. As part of the new process, drug makers need to submit estimated production timelines before receiving a quota and must now apply for allotments on a quarterly basis, instead of annually.

Another aspect of the shortages have to do with the low prices of generic drugs, which often make it difficult for manufacturers to compete. In an interview with Axios, Ganio called this “a race to the bottom,” explaining that when price-sensitive buyers choose the cheapest generics on the market, they may also often be getting drugs of a bare minimum quality. Many of these most inexpensive generics are made overseas, in countries like India and China. “There’s really not a lot of economic interest in getting into this market or expanding a portfolio into this market,” Ganio told PBS.

ONE 💉 THING

The medical shortages are on the minds of presidential candidates as well. Donald Trump, who passed an executive order during his last term in office to ensure that essential drugs are made in the U.S., has promised to bring the manufacturing of “all essential medicines” back to U.S. shores. And last November, President Joe Biden laid out a plan to use the Defense Production Act, which dates back to the time of the Korean War, to direct private companies in the U.S. to make more essential drugs. This past week, Medicare set out incentives (pdf) for around 500 small hospitals to build and maintain a six-month stock of essential drugs.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a pharmaceutical-drama-free weekend!

— Samanth Subramanian, Weekend Brief editor; and Bruce Gil, staff writer