America's drone deficit

How can the U.S. bring back domestic drone-making to keep the country's secrets safe?

Hello, Quartz members!

Suggested Reading

As the war in Ukraine has brought home to many people, drones are the new tool of power. But most of the drones in the world today are made in China, by companies with close ties to the People’s Liberation Army and the Communist Party. That’s got U.S. leaders and the military worried. Today we take a look at America’s drone deficit.

Drones, drones, everywhere

Engineers use them to monitor dams. Energy companies use them to inspect pipelines. Emergency services use them to be first on the scene at a fire, a traffic accident, or even a crime. Drones are a growing part of daily life in the U.S. Farmers use specialized drones to monitor crops in the field, letting them optimize planting and care — or keep an eye on livestock. Architects use them to inspect building facades, and plants and businesses use them as a low-cost security “eye in the sky.” The U.S. military, having seen how drones have changed the face of the war in Ukraine, has been launching drone programs and integrating drones into its strategy and tactics.

But as drones grow in use and usefulness, with annual sales expected to rise from $6.58 billion in 2024 to $31.3 billion in 2034, a major problem is appearing: Most of the drones used in the U.S., including those used by first responders and for infrastructure upkeep and surveillance, are made in China. And increasingly, they’ve been found capable of sending data back to the Chinese companies that built them.

In January, the FBI and the new U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency warned that Chinese-made drones “risk exposing sensitive information to [Chinese] authorities, jeopardizing U.S. national security, economic security and public health and safety.” With China increasingly seen as an adversary of the U.S., if not quite an enemy, the agencies warned that collecting data is a key part of China’s “geopolitical competition” with the U.S.

“China currently controls a whopping 90% of the U.S. drone market,” Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, an Illinois Democrat and the ranking member on the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, said in a hearing on Wednesday.

So what to do about it? Krishnamoorthi drew an analogy to the Chinese swimmers who are competing in the Paris Olympics despite having doped themselves at the last Olympics: “Because the [Chinese Communist Party] is currently not playing fair, we need to do two things. One, we need to stop the CCP from breaking the rules. And two, we need to invest in ourselves to win.”

Late last year, the U.S. banned the purchase of Chinese-made drones with federal funds, as part of the annual defense spending bill signed into law by President Joe Biden. Another bill in Congress, introduced by New York Republican Rep. Elise Stefanik, would specifically ban the purchase or use on government-funded projects of drones by DJI, the Chinese drone maker that controls about 70% of the global drone market.

But the bans only solve half the problem, says Allan Evans, CEO of Florida-based specialty drone maker Unusual Machines. Much like the CHIPS Act — the $50-billion program Biden signed into law that includes tax breaks, subsidies, and cheap loans to bring semiconductor production back to the U.S. and reduce the risk that China can disrupt the chip supply — Evans and others in the industry see a need for manufacturing incentives to rebuild a domestic drone industry before the bans come into place.

“Not only do you need a marketplace, but for production you need to be big enough to get the flywheel spinning,” Evans said in an interview. “If you finance it earlier, the marketplace can take care of it.”

The re-shoring challenge

Bringing drone making back to the U.S. will be an expensive and potentially impossible task

As the Atlantic Council noted in a report this month, China has built a “near-insurmountable lead” in manufacturing drones, using “unfair trading practices” that have let it dominate the $31 billion global drone market.

“China benefits from a manufacturing ecosystem that goes back many decades,” Adam Bry, CEO of Skydio, a U.S. specialty drone maker, told CNBC last year. Because the Chinese have been building consumer drones for almost two decades, their drones are simply cheaper than anything the U.S. can produce.

Government incentives to buy U.S.-made drones, and prohibitions on buying Chinese-made drones, are key parts of growing the domestic drone industry and part of a bill introduced by Stefanik called Drones for First Responders Act. The legislation would put tariffs on Chinese drones and use the revenue for first responders and others to buy U.S.-made drones.

China’s recent efforts to cut off Ukraine’s drone supply show the need for re-shoring, the Atlantic Council noted, arguing that China could do the same to the U.S. and its allies.

Some American agencies are already taking their own action and devising hybrid solutions. Police in Fremont, California replaced all the Chinese software in their drones with U.S.-engineered software, and store the data on U.S. servers to keep it confidential.

Evans of Unusual Machines said the endgame has to be re-shoring the production of consumer drones, as well as commercial drones. He noted that U.S. companies like GoPro once made a large portion of their drones in the U.S. They offshored them to China.

Michael Robbins, a drone industry lobbyist, said re-shoring can work: “Our belief is that it can be tackled through two distinct ways,” said Robbins, CEO of the Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International. “One is a demand signal from the U.S. government that they’re going to purchase a significant number of drones for the U.S. or for allies like the Ukrainians.” The other, he said, is federal seed money for private firms that will build drones and parts of the drone supply chain.

But it may already be too late. DJI and Autel are reportedly setting up U.S. companies that would license their designs, and use parts sourced outside China to build the same drones they are now making, but that would be banned in the U.S. for security concerns. The Hill reported this month that DJI partnered with a U.S.-based company called Anzu Robotics to license its technology for sale in the American market. Hong Kong-based Cogito Tech Company Limited registered through the FCC last year to sell drones in the United States, and two of its drones are nearly identical to products produced by DJI.

Anzu says it is a U.S.-owned company with U.S.-based servers, U.S.-based support, and U.S.-based service and repair.

But as Evans said in an interview, the key to re-shoring is an affordable U.S. supply chain — with cameras, motors, softwar,e and other parts of the drone ecosystem sourced domestically or from reliable allies overseas. “Until those are onshored and made affordable, it’s very difficult to make anything affordable that can compare with China,” he said.

What’s the Pentagon doing?

The extraordinary success of Ukraine’s beleaguered military in holding off a much larger Russian invasion force with the use of drones has inspired the U.S. to take a new look at what are now called “uncrewed” platforms.

Last August, Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks unveiled the Replicator strategy, a plan to deploy thousands of drones within two years, to deter a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or other Chinese action in Asia. The Pentagon has solicited new designs and speedy low-cost manufacturing programs from both traditional defense contractors and civilian firms. So far, the Pentagon has been (necessarily) secretive about the program. But Hicks said the first Replicator drones were delivered in May, and that the military is on target to deploy thousands of drones in Asia by August 2025.

They include weapons like the AeroVironment’s Switchblade 600, a loitering munition that can be carried and fired by a single soldier. Another new program deploys a 3-D printer to create mission-specific drones on the battlefield for as little as $50 apiece. It will also include maritime drones that can do everything from clear sea mines, a notoriously slow and dangerous task for human divers, to patrolling the sea for submarines or delivering mines, missiles or torpedoes against surface ships.

The U.S. has been inspired by Ukraine’s astounding success in using surface drones — known as USVs, or uncrewed surface vessels — to blow up Russian warships, and, combined with longer-range US-made rockets, to force the Russian fleet from its base in Crime to a corner of the Black sea.

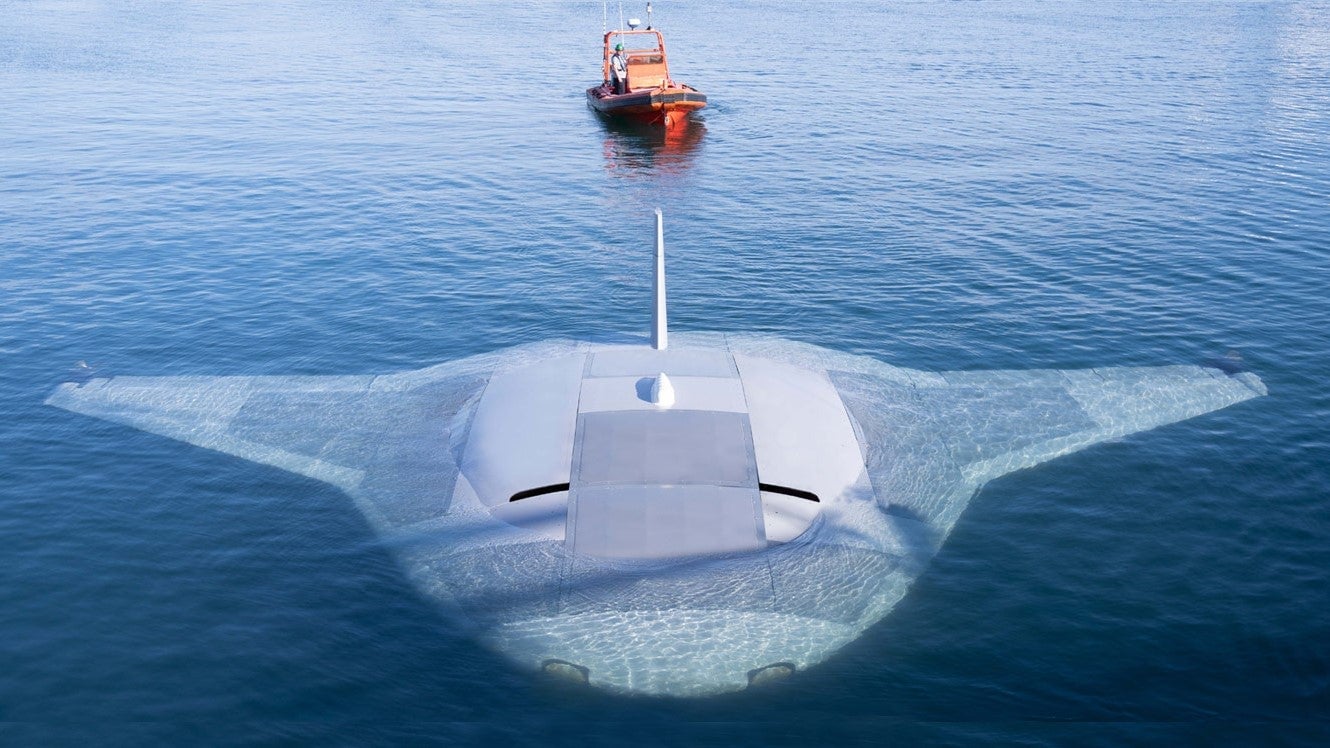

New U.S. naval drones include Northrup Grumman’s Manta Ray, a large drone shaped like the winged fish that can stay underwater for months. Its payload is classified, but in January the Navy put out a call for small USVs that can travel hundreds of miles and swarm enemy positions, confusing the battlefield and delivering a succession of small punches at enemy positions (think a fleet of remote controlled or autonomous armed Boston Whalers).

U.S. naval drone makers applaud the Replicator initiative. Philip Stratmann, CEO of Ocean Power Technologies, a New Jersey-based maker of small sea drones, said the drones are now having their moment, and the U.S. is moving swiftly into the lead. “If the Russian invasion of Ukraine has shown us anything, it’s that one of the largest militaries in the world can’t overcome a small force that is using drones in the inshore space,” he said. “How do you protect your big naval assets if you’ve got a $100,000 sea drone taking out a billion-dollar Black Sea Fleet vessel?”

Thanks for reading and have a great weekend.

— Peter Green, Weekend Brief writer