Quartzy: the under pressure edition

Happy Friday!

Happy Friday!

“In a so-called high-pressure age we are now doing high-pressure cooking,” wrote Jane Nickerson for the The New York Times in April of 1946, in a phrase that might well be applied to us some 70 years later. Back then, home cooks in the post-war era were all about their pressure cookers. In 1950, The New York Times estimated that 37% of US households owned at least one. Then—thanks, microwave—they fell out of favor. Until the Instant Pot came along.

The Instant Pot, for the uninitiated, is a Canadian-designed electric multi-cooker (including functions for pressure cooking, slow cooking, sautéing, making yogurt, and more). It has gone viral, with a Facebook community of 1.2 million fans, countless blogs devoted to “IP” cookery, and Slate declaring the appliance—which once sold 215,000 units on Amazon in a single day—to be “an entire economy and a religion.”

I finally got one after Thanksgiving, when cooking without one started to feel like abstaining from Stranger Things. Everyone was talking about it, and I just wanted to participate in society again.

What’s all the fuss about? Well, for one thing, pressure cookers are fast. The sealed environment of a pressure cooker means that water boils at a higher temperature (because physics), which allows food to cook much faster. They also cook some foods better: Quartz’s resident physics expert and longtime pressure cooker enthusiast Akshat Rathi adds that the high-pressure steam trapped inside a pressure cooker forces itself inside ingredients like uncooked rice, helping them to retain moisture. And because it does so uniformly, the result is pleasantly puffed up, well-cooked rice.

That said, they’re not “instant.” When I asked you readers a while back whether you had an Instant Pot—and whether I needed one—several of you responded with this warning: Instant is a misnomer! The device can take about 10 minutes to come up to high pressure, and then another 10 or 15 to come back down using “natural release,” so a recipe with a 30-minute cook-time at pressure might actually take more like 50 minutes from start to finish in the Instant Pot. (That said, the cook-time for the risotto I made for lunch was six minutes, SO.)

As I warm up to my Instant Pot, I’ve continuously consulted Quartzy editor Indrani Sen—a seasoned cook and mother of two who cooks deliciously unfussy meals and has no fears of gadgetry—for pro-tips. She advises thinking of Instant Pot cooking in three ways:

Weeknight cooking: These are things that can basically be done in 30 minutes or less, like the aforementioned risotto, a side of brown rice or mashed potatoes, or Urvashi Pitre’s internet-famous butter chicken curry. These recipes and shortcuts are not to be confused, as Sam Sifton also cautioned in his newsletter, with…

Project cooking: These are things like Korean short ribs, pot roast, or a whole pork shoulder (perfect for leftover carnitas), which take at least an hour with pressurizing and depressurizing, so are better relegated to weekends or afternoons, long before anyone’s hangry.

Advanced prep: This seems to be where the love for the Instant Pot remains, long after the novelty has worn off. Hard-cook a dozen eggs to your precise liking—and pickle them if you like!—or cook a pound of beans you can split into soups and salads, or a pot of bone broth (aka stock) to feed you through the week.

And a couple more things: Even if you’re a slow cooker-devotee, resign yourself to the idea that a pressure cooker function of your Instant Pot will probably make things taste better. About the sauté function—If you like a deeply burnished piece of meat and have time to sauté before you braise, go for it. But with most stews and longer-cooked meat dishes, the difference browning makes in the final flavor is pretty minimal, so if you’re short on time, skip it. If you’re an avid baker, you should keep using the dry heat of your oven. I’m not here for Instant Pot banana bread; and the next internet-famous dessert I attempt will absolutely be Alison Roman’s chocolate chunk shortbread cookies.

Enough Instant Pot talk. For me, when it comes to letting off steam (sorry!), there is nothing quite like curling up in front of an awe-inspiring ocean documentary. So I am thrilled about the US debut of Blue Planet II, the BBC’s blockbuster docu-series narrated by Sir David Attenborough, which the Atlantic just called “the greatest nature series of all time.” (If you love nature and/or Attenborough, listen to him chat with David Remnick on The New Yorker Radio Hour.)

The series opens with a goose-bump-inducing slow-motion shot of a roaring wave, before a pod of bottlenose dolphins shatters the surface, surfing and soaring “for the sheer joy of it.” We follow the dolphins to a reef in the Red Sea, where they teach a calf how to rub itself on a coral that scientists have discovered to have anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory properties. That’s the first five minutes, and you just know this is going to be the best.

Over the course of seven one-hour episodes, Blue Planet II travels the world’s oceans, filming underwater volcanoes (at top) and in depths previously thought unable to support life—think seven miles down, where the pressure is equal to 50 jumbo jets stacked on top of one another—but surprise: There are creatures down there!

In the US and Canada, it’s airing Saturday nights on BBC America, and if you have a cable or satellite subscription you can watch it on BBC.com. Here are more channels and airdates worldwide. If you need a little ocean wonder to tide you over in the meantime, check out Quartz’s video series “In the Deep,” which includes great white sharks and hypnotic jellyfish.

I’ll be away next week, so you can look forward to a letter from Quartz’s wonderful new London-based reporter, Rosie Spinks. Have a great weekend!

[quartzy-signature]

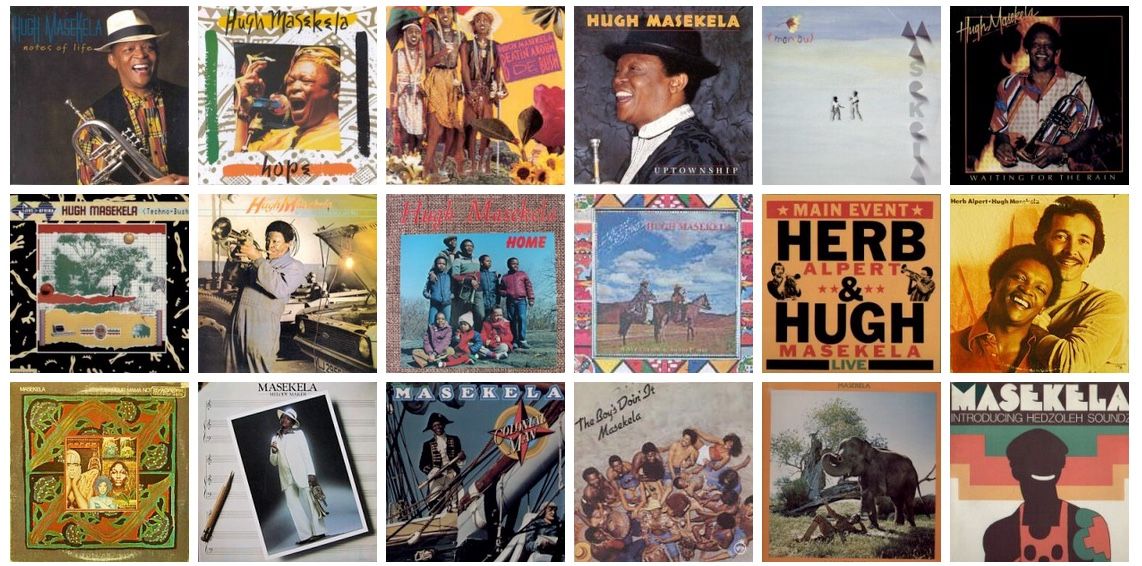

Farewell to the legendary trumpeter, Hugh Masekela. “South Africa’s father of jazz” and anti-apartheid activist died this week of prostate cancer. Quartz’s Lynsey Chutel chronicled Masekela’s musical catalogue through his decades of collaborations while in exile from South Africa.

“He’d learned to play on a trumpet donated by Louis Armstrong and in the US was tutored by Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie,” wrote Lynsey. “But when it came to producing his own music, harked back to life in South Africa’s black townships.” Despite popular success and collaborating with musicians from Fela Kuti to Paul Simon, Masekela said he only felt his career truly began after he returned home to South Africa in 1990.

Check out Lynsey’s story for links to great songs and albums, from the 1968 no. 1 hit “Grazin’ in the Grass” to a 2015 performance of his anti-apartheid anthem “Mandela (Bring Him Back Home).”