Jazz used to be a music you got down to. Before it became the background music for posh restaurants with crisp linens and clubs with velvet couches, it was the music of scuffed floors in illegal shebeens or backyard taverns. That was the jazz that gave the world Hugh Masekela and it was the ideal of the music he clung to until his death on Jan. 23, 2018 at age 78.

Audiences at a Masekela concert would inevitably dance, often after Bra Hugh (as he was affectionately known) demanded that they join him as he got down, instrument in hand just as he might have in Sophiatown in the 1950s. If you’d come to party, you would also leave with a deeper sense of South African and the world’s political struggle as Masekela used his music for activism.

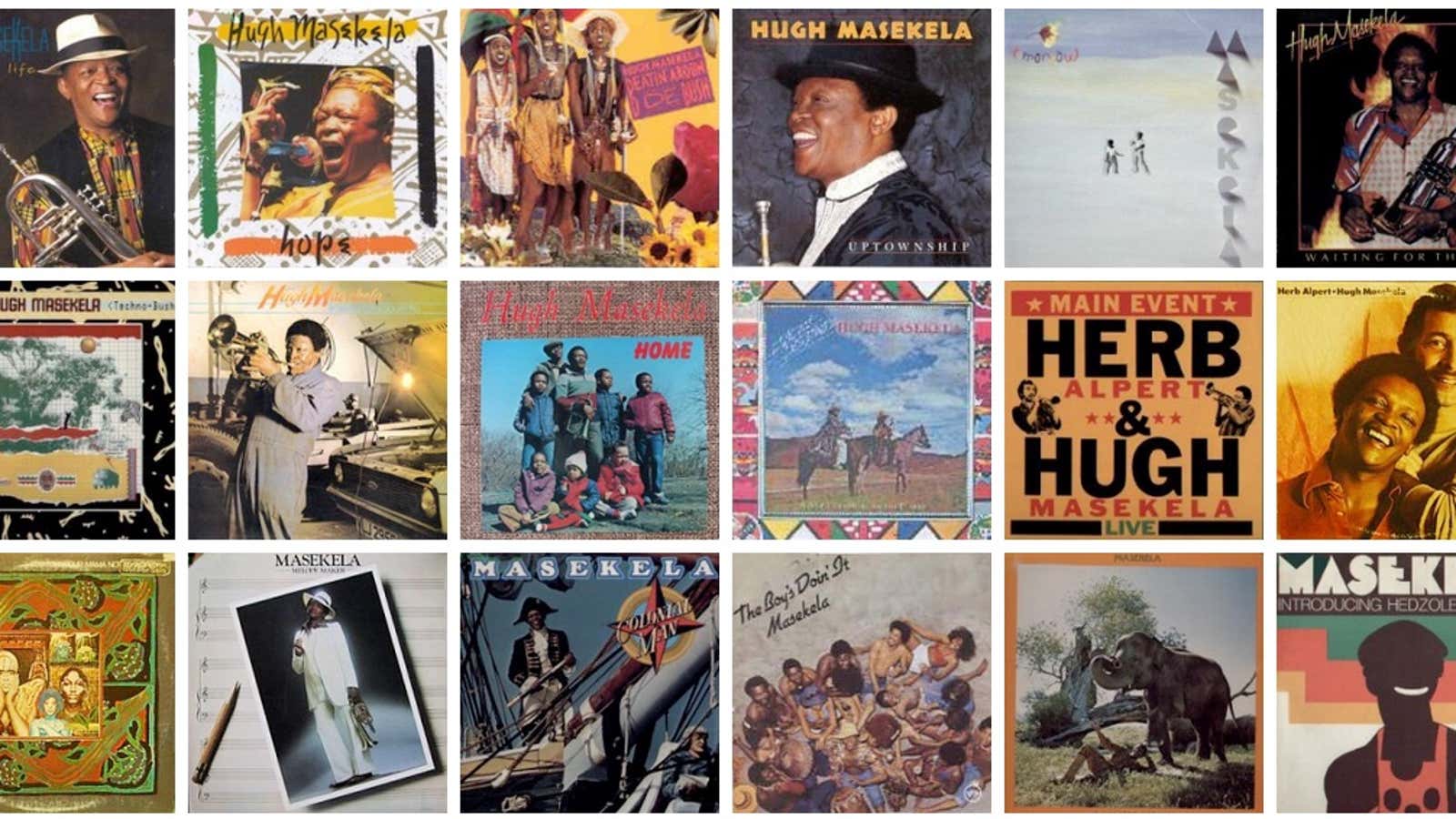

Masekela is known as South Africa’s “Father of Jazz” but his music shows off a tendency to push against the narrow definitions as he collaborated with musicians from around the world. A multi-instrumentalist who championed musicians’ creative and economic rights, he was also keen to collaborate across the generations as he pushed his sound. Across six decades and dozens of albums, Masekela was able to reinvent himself while retaining an authenticity rooted in South Africa.

“Other South African musicians have succeeded overseas; many have made one mid-career image switch—but few have shown us, in only one person and more than 30 albums, so many of the faces and possibilities of South African jazz,” wrote jazz historian Gwen Ansell.

Early in his career, Masekela played with musicians who would go on to become icons in their own right. A young Masekela played trumpet and flugelhorn alongside Abdullah Ibrahim, Jonas Gwangwa and Kippie Moeketsi to record one of South Africa’s first original jazz albums, borrowing from traditional mbaqanga music and American bebop. At 19, one of his first international tours, however, was as part of an orchestra for the musical King Kong in 1958, where he met his future wife Miriam Makeba as she sang the lead role.

Masekela went into exile in 1961, first to London and then New York. He’d learned to play on a trumpet donated by Louis Armstrong and in the US was tutored by Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie. He got to see the greats like Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Thelonius Monk but when it came to producing his own music, harked back to life in South Africa’s black townships. In 1968, his single Grazin’ in the Grass went to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

In the late 1970s he collaborated with fellow trumpeter on Herb Alpert on a couple of albums including their disco/brass cover of the Zimbabwean classic, Skokiaan, seen here performed on the Soul Train TV show in 1978.

Masekela left the US and returned to the continent, where he sought out local musicians at a time when Highlife and Afrobeat were the heady soundtracks of postcolonial independence. After an introduction by Fela Kuti, Masekela teamed up with Ghanaian band Hedzoleh Soundz for the album Masekela Introducing Hedzoleh Soundz.

In Botswana in the 1980s, Masekela experimented with techno on the 1984 album Techno-Bush, that saw him add synthesizers to his signature flugelhorn sound. In Botswana, he teamed up with the band Kalahari and joined Paul Simon’s Graceland tour.

When he returned home as apartheid ended, Masekela embraced the sounds of a new generation, producing a hit with the kwaito generation’s icon, Thandiswa Mazwai, and later working with house music duo Brothers of Peace. His last concert was to be collaboration with rapper Riky Rick. Already a veteran musician, Masekela felt his career only began when he returned to South Africa.

“To tell you the truth, until I came back here, which I never thought I would, my career never really started. It only started in 1990. We lived here vicariously, so being here is like being a pig in swill,” Masekela said after returning home.

Until near his death, Masekela continued to tour and collaborate. Celebrating South Africa’s 21st anniversary of freedom at the International Jazz Day concert in 2015, Masekela revisited Mandela (Bring Him Back Home) alongside contemporary jazz composer Marcus Miller. By then, Masekela had built up the kind of career that the 14-year-old learning on a donated trumpet in apartheid South Africa could only dream of. Still, he paid tribute to the political leaders who inspired his activism as he brought even more musicians into his fold.

“All those wonderful old geysers, many of them are leaving us now and the ones that are still with us are very frail and old,” he told the audience in Paris. “But, we will always cherish the legacy and the heritage they left for us.”