Quartzy: the real men edition

Happy Friday!

Happy Friday!

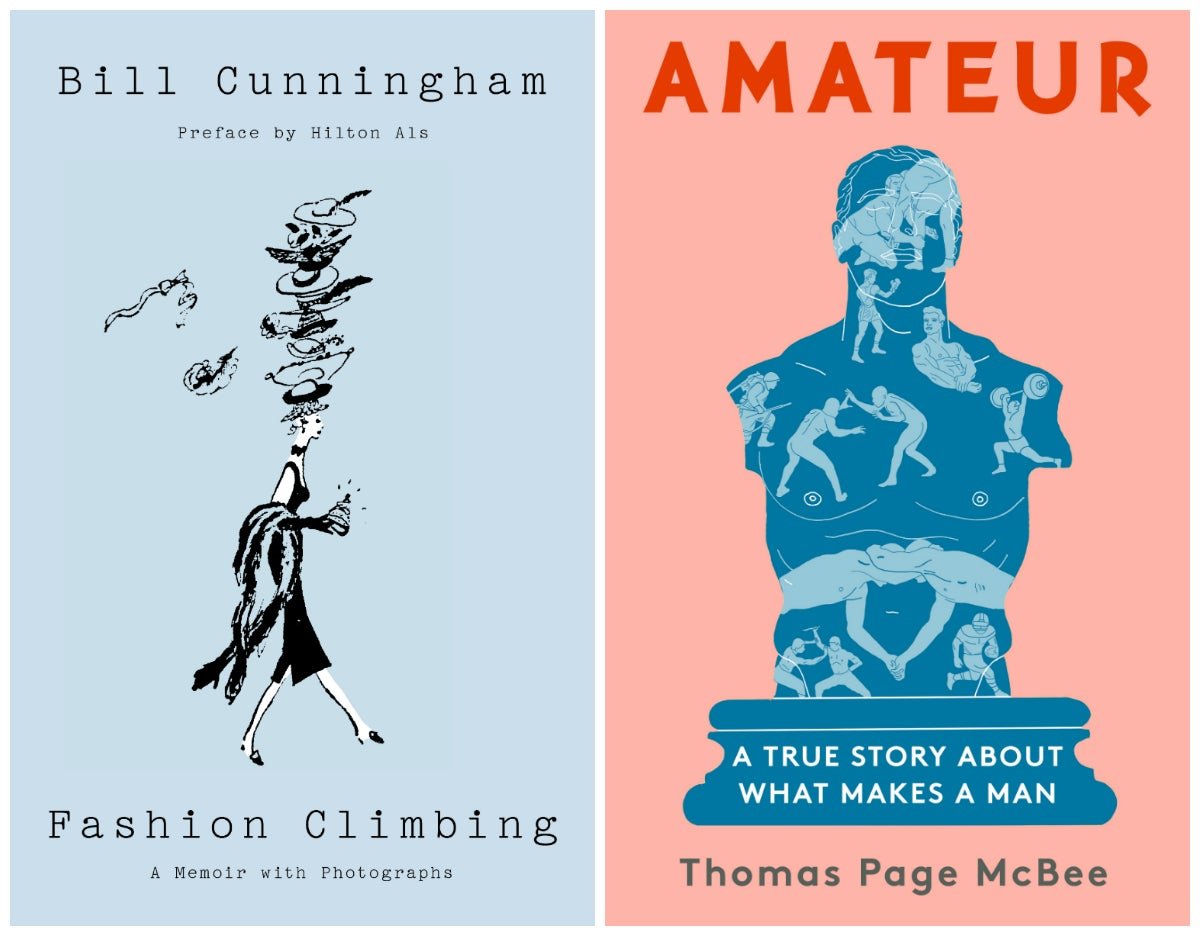

I recently happened to pick up two new books in tandem: Thomas Page McBee’s Amateur, the story of how McBee (who is a former editor here at Quartz) came to be the first trans man to box at Madison Square Garden in 2015, and Bill Cunningham’s Fashion Climbing, a posthumous memoir about the beloved New York Times photographer’s blossoming as a milliner and fashion world documentarian in the 1950s and 1960s.

On their faces, these two authors don’t appear to have much in common. McBee was recently pictured tattooed, unsmiling, and shirtless in boxing gloves, on the cover of a magazine. Cunningham is fondly remembered for his wide toothy grin and French blue workman’s jacket, snapping his camera to document the city’s most outrageous dressers and swish social events.

But both men’s biographies begin with childhood violence and shame surrounding society’s gendered expectations. Cunningham’s first fashion memory is the beating he took at age four after being discovered wearing his sister’s pink organdy dress. Before the age of 10, McBee endured years of sexual abuse by his stepfather. McBee has grappled, as he said last weekend during a talk at Skylight Books in Los Angeles, with a question: “How do I become a man even though I’m so afraid of men?”

In the age of “toxic masculinity”—the epidemic of male entitlement, alienation, and violence that underlies the #MeToo movement’s tidal wave of trauma, as well as alarmingly high suicide rates for middle-aged men—these two books offer powerful, personal counter-narratives to the notion that manhood is defined by dominant and macho behavior. Both McBee and Cunningham demonstrate how men can fight for a better definition of manhood—one that includes vulnerability, empathy, and self-expression—simply by fighting to be themselves.

Fashion Climbing documents the decades before Cunningham became a photographer, from his upbringing in conservative Boston to landing a column in Women’s Wear and covering European fashion shows in the 1960s. Most of the pages in between are devoted to his early career as a milliner, a medium that was a true passion—and which brought, in his telling, endless shame to his family. He describes using his boyhood snow-shoveling savings to buy the supplies to make his mother a hat: “It was a real dilly—a great big cabbage rose hung over the right eye.”

“My mother nearly collapsed in shame when she saw it,” he writes, “‘Think what the neighbors will say!’ These were famous last words with my mother and dad.”

So it feels like a triumph to watch Cunningham persevere—as an assistant in a fancy department store, as a hat-maker to Manhattan’s high society, as a private during the Korean War, training in a helmet “covered with a dazzling garden of flowers and grass,” and as a candid fashion columnist fighting his editor for his integrity. And to know that after the personal journey in Fashion Climbing took place, he would go on to celebrate that self-expression in others. As a photographer for The New York Times’ style pages, sure, he shot Manhattan’s society swans—but he also always made a point of celebrating those who let their freak flags fly.

Go forward. This perseverance adds up to what McBee writes in Amateur, to be the Latin root of the word of that most masculine of words: aggression. It doesn’t mean to pound one’s chest or to threaten another man, but rather simply, to go forward.

This is the same instruction that McBee’s coach, Danny, shouts at him during sparring bouts.

“At the gym, Danny and Stephen and the rest of the guys called up that force in me, like magicians, and I allowed it—not, I realized, because it was gendered, but because it was necessary. To go forward,” McBee writes. “‘Now, again,’ Danny said through his gloves, calling me forward.”

The story of McBee’s training gives his well-reported inquiry a fast-reading personal story filled with relatable and recognizable characters and conversations. And his interviews with scholars such as Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford neuroscientist who studies the nuances of testosterone and behavior, bring a greater depth of understanding to these interactions.

Sapolsky explains that testosterone doesn’t increase aggression as we understand it, but rather one’s willingness to do whatever is necessary to maintain status. If that means cooperation and collaboration, so be it. The problem is that often in our society, especially for men, it doesn’t.

“If our world is riddled with male violence, the core problem isn’t that testosterone can often increase levels of aggression,” Sapolsky tells McBee. “The problem is the frequency with which we reward aggression.”

Something better. And yet, in the boxing gym, McBee is surprised to find a space where men are vulnerable, affectionate, and supportive.

“If an alien had landed in that boxing gym and had to describe the behavior of male humans,” he writes, “surely it would have concluded that we touched each other as much in love as in violence—that the former, in fact, inspired the latter. If anything appeared ‘innate,’ it would surely be the affection between us.”

The cover of violence, he says, made it somehow safer to behave in ways that society might otherwise frown upon. The freedom that McBee found in fighting—a place to express and explore his own humanity—is not unlike the Shangri La that Cunningham finally found in fashion, with feathers and flowers flying about his studio.

As Cunningham fought to realize his creative vision—“And what a fight it was!” he writes—McBee fights to understand what it means to be a “real man.” He finds the answer not in knocking out another man’s mouthguard, but rather in moments of vulnerability, closeness, and empathy.

“What made me feel ‘real’?” McBee asks. “When [my coach] tied my glove on for me or poured water in my mouth, or when I tripped over the jump rope and had to begin again. I felt real when I asked for help, when I failed, when I was myself. I did not want to become a real man, I realized. I was fighting for something better.”

Have a great weekend!

[quartzy-signature]

RIP Burt Reynolds. Once described as the “standard of hirsute masculinity,” Burt Reynolds, who came to acting after a knee injury ended his college football career, died yesterday at 82. Men and women alike remember him as an iconic heartthrob thanks to his easy smile, self-deprecating humor, and truly impressive mustache. I don’t think I’ve got a Deliverance screening in me this weekend, but could definitely check out Smokey and the Bandit with Sally Field (and some outstanding seventies-era western menswear), or one of his extensive list of rom-coms: “Starting Over (1979) opposite Jill Clayburgh and Candice Bergen; The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982) with Dolly Parton; Best Friends (1982) with Goldie Hawn; and, quite aptly, The Man Who Loved Women (1983) with Julie Andrews.” What a lucky guy.