Whether the planets be actually inhabited &c.

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

It’s the fifth edition of Space Business, Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extra-terrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Independence day, the great Gateway debate, and a space station for the Pentagon.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Happy Independence Day to my American readers! Space has always been part of the fabric of American culture, even before we split off from our colonial masters.

Astronomy was a current interest for gentlemen scientists, and a signal of enlightenment. A 1774 diary entry reported by Alexander MacDonald in his book The Long Space Age relates a casual conversation between an influential Virginia planter and a young friend on topics including, “Philosophy, on Eclipses; the manner of viewing them; Then to Telescopes, & the information which they afforded us of the Solar System; Whether the planets be actually inhabited &c.”

Then and now, space science was vital to the projection of power across the globe. In the 18th century, astronomers sought to measure the transit of Venus across the sun, in order to derive the distance between the Earth and the sun, among other sought-after facts. The transit only occurs about every 120 years, and the 1769 event would be the last chance in anyone’s lifetime. The great powers sent expeditions to observe the transit, and so did the nascent American Philosophical Society. Seven years later, when the Declaration of Independence was read aloud to the public for the first time, it was from the platform that had housed a temporary observatory for the 1769 transit.

Space spending controversies aren’t new either: In 1825, after President John Quincy Adams noted with dismay that Europe had hundreds of observatories, but the US had none, his proposal for a national observatory sparked controversy. His flowery language for observatories, “lighthouses of the skies,” was twisted to “light-houses in the skies,” which became a political slur for decades, the 19th century equivalent of the “bridge to nowhere.”

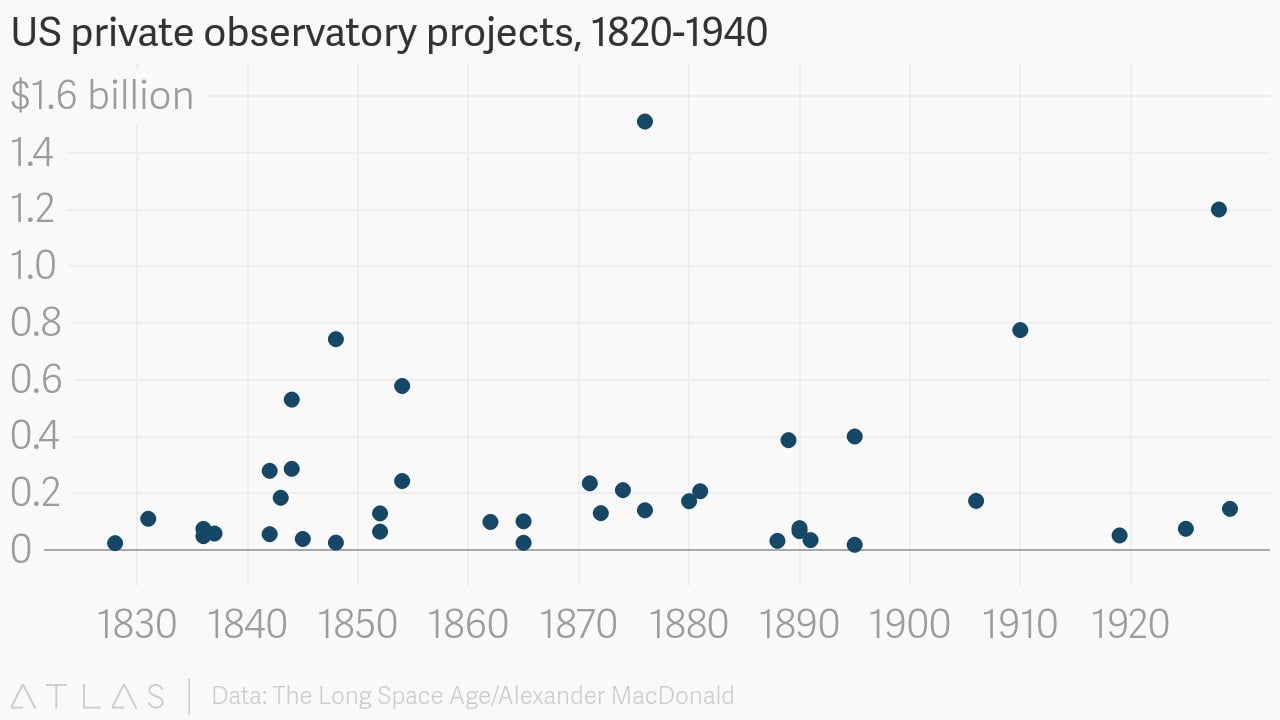

But Adams was right about the trends, including a burgeoning national identity, and mass interest in science. The American “age of telescopes” was about to kick off. Arguably, the first space mega-project in American history began in the year 1828, when Yale imported a European telescope at the cost, adjusted to today’s economy, of more than $24 million. Many others, with investment comparable to contemporary NASA space missions, would be built in the years ahead, often by ultra-wealthy individuals seeking to to gain prestige and demonstrate mastery.

By the 20th century, the military applications of space technology, and particularly rockets, had made the military a major funder of space activity for pioneers like Robert Goddard, the inventor of the liquid-fueled rocket engine. But the Apollo program we commemorate later this month grew from the same desires of our colonial forebears: To show that we’re just as good as the other guys, if not better. If that’s not the spirit of Independence Day, I’m not sure what is.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude: The only time the Space Shuttle flew on Independence Day was in 2006, when Discovery flew to the International Space Station. Of course, it was not on purpose—the launch had been planned for July 2 and was delayed due to weather concerns.

This was just the second shuttle mission following the Columbia disaster in 2003, which ultimately led to the end of the space shuttle program and set the stage for the rise of the private space industry.

🌘 🌘 🌘

SPACE DEBRIS

ABORT. NASA’s Orion spacecraft successfully performed an abort test on July 2. The demonstration shows that if something were to go wrong with its rocket during a real launch, the spacecraft can safely escape with its crew of astronauts. That’s good news for NASA’s ambitions to head for deep space, but don’t get it twisted: NASA has been developing this spacecraft for 14 years, and it’s not enough to get to Mars or the Moon on its own. There’s at least three other big things needed for a lunar mission that NASA just doesn’t have: A rocket big enough to carry it, a moon-orbiting way station to dock with, a lunar lander to carry astronauts to the surface and back.

Gated Community. Speaking of that moon-orbiting way station: NASA calls it the Lunar Gateway, and the White House may not let them build it. Eric Berger has the latest on the Trump administration’s attempt to rush a moon landing in 2024. NASA has proposed that lunar-bound astronauts fly to the moon-orbiting Gateway, and from there head to the surface. The White House Office of Management and Budget seems to agree with people like Buzz Aldrin that it’s a waste of time compared to just flying Orion to a lander waiting in orbit around the moon. But NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine insists that this is for sustainability—long-term, reliable lunar access. Some NASA insiders see the Gateway as sustainable in the political-industrial sense: A long-term contract to keep private industry aligned with the government. They also believe the Gateway could enable deep space activities unrelated to the moon—if, say, a new president arrives in 2021 and cancels Trump’s lunar dash.

National Security Space Station. The Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit asked private companies what it would cost to build a free-flying pressurized habitat in orbit, akin to similar discussions on the civil side. The volume for this initial prototype will be just one cubic meter, and the design is intended as a test-bed for space payloads and manufacturing efforts. Why would they want something like this? There are likely plenty of classified reasons, but the US military does plenty of testing in space already, using its X-37B space drone or missions like the recent Falcon Heavy launch. Having its own free-flying space station might be more cost-effective if activity in space is ramping up. As a side note, the Congressional bean-counters just announced the cost of standing up an independent Space Force: Some $3.6 billion.

Traffic Management Management. In a new Politico interview, Kevin O’Connell, the head of the Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce, talks about getting space traffic management out of the military and into civilian hands. It’s a mammoth task, especially because Congress has yet to approve it, but O’Connell is focusing on building up much-needed expertise in his department and figuring out how to bring competing stakeholders together around common standards. “Historically we’ve waited until someone knocked on our door for a license to think about regulation,” he said. “My argument is that’s way too late. We need to improve our understanding of the space economy.” One source for inspiration might be New Zealand.

Payload Payday. I’ve told you before not to bet on a human landing on the moon by 2024, but NASA’s program to send robotic explorers to the moon sits squarely in the Venn diagram of feasible, worthwhile and scientifically-meaningful space activity. The agency announced 12 different projects it wants to send to the lunar surface, including technology to enable future activities like new rovers and robotic arms, and instruments to pursue fundamental questions about the moon and the resources, like water ice, it is believed to contain.

ANOMALY REPORT: Last week, this newsletter erroneously reported that a Rocket Lab launch occurred on June 27 in New Zealand, when in fact it was delayed until a successful launch on June 29. After reviewing extensive telemetry feeds, engineers have determined that the root cause was human error while updating the draft e-mail in the Quartz content management system. Steps have been taken to isolate this process and ensure that future e-mail launches will only contain factual information. I regret the error.

your pal,

Hope your week is out of this world. Please send your 17th century space philosophies, Gateways of all kinds, tips and informed opinions to [email protected].