Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The SLS breaches its baseline, an Apollo spacewalk and a cash infusion for SpaceX.

🚀 🚀 🚀

Perhaps the most pivotal moment in the 21st century US space program came in 2010, when president Barack Obama canceled predecessor George W. Bush’s plan to return to the moon.

Ending the Constellation program was not easy for Obama, and it created political problems for him in Florida, Alabama and Texas. NASA lifers were stunned. One told me that attending a senior staff meeting at Johnson Space Center that day was like going to a funeral.

The decision was made on a dollars and cents basis. Described by one architect as “Apollo on steroids,” Constellation proved simply too expensive. Three years into the project, auditors reported (pdf) that “NASA does not know how much Ares I and Orion [the rocket and spacecraft at the heart of the program] will ultimately cost, and will not know until technical and design challenges have been addressed.”

Canceling the moon mission allowed the agency to re-focus on low-Earth orbit and then-nascent commercial partnerships that have so far provided all of NASA’s new space vehicles in the 21st century.

But Constellation didn’t really end. Powerful senators like Alabama’s Richard Shelby, and powerful companies like Boeing, were able to push through a re-purposing of the vehicles for deep space exploration. Orion and the rocket, now called the Space Launch System (SLS), are at the heart of Artemis, NASA’s plan to return astronauts—including the first woman—to the moon by 2024.

This week, NASA’s inspector general (pdf) found that SLS has now gone more than 30% over its predicted budget. This triggers a requirement for NASA to notify Congress of the overage, and for lawmakers, already reluctant to bet on a lunar return, to vote on re-authorizing the program.

This reckoning was delayed thanks to some accounting tricks at NASA—in 2017, the inspector general reports, the agency changed its accounting of the project to reclassify $1 billion in spending, “thereby masking the impact of Artemis I’s projected 19-month schedule delay.” Overall, some $6 billion in spending on the rocket hasn’t been included in the project’s baseline.

The future of those vehicles may now hang on the 2020 election. A second Trump term means Republicans are unlikely to worry about the debt. The administration has at times put the lunar return at the center of its space program, depending on who the president spoke to last. But a Democratic administration, armed with big plans for domestic spending and undoubtedly facing Republican demands for budget cuts, may be more inclined to question the $35 billion or more requested by NASA to get to the moon in the next four years.

NASA is aware of the risk. Asked last summer about why the US should accelerate its return to the moon from 2028 to 2024, administrator Jim Bridenstine referenced Bush’s plan, noting that “it took too long, cost too much money, the political risk caught up to it.” Expediting NASA’s lunar landing was his way to reduce that risk, but a year after setting the goal, NASA still lacks a firm plan for how to get back to the moon.

Lawmakers are often reluctant to shift spending or cut jobs in the face of a troubled project, as shown by the zombie-like forward stagger of the SLS. But this breach is a reminder of the last time patience with the space agency ran out—and that it might again in the future.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude

SpaceX consultant and former astronaut Garret Reisman reminded me that some 51 years ago, Apollo astronaut Rusty Schweickart performed the program’s first spacewalk during a shakedown cruise of the lunar module. He took this photo of one of his colleagues, David Scott, standing in the open door of the Apollo command module on March 6, 1969:

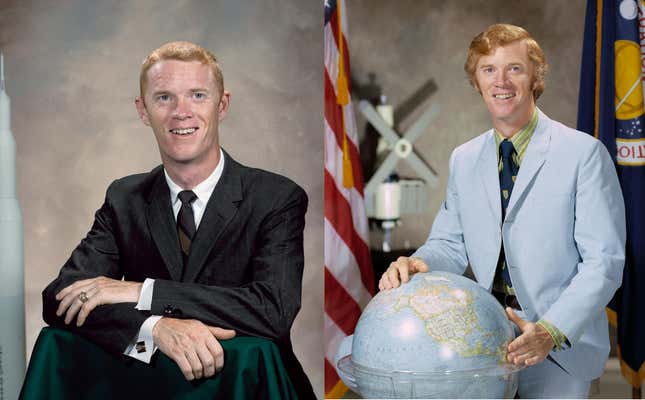

On another Schweickart note—as part of my continuing obsession with NASA’s formal portraits, I can say that two portraits of Rusty, from 1964 and 1971, respectively, do a lot to explain how the space program (and the US) changed during those years:

🛸 🛸 🛸

🚨 Read this 🚨

I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I’ve been taught racism. AI can be prejudiced, just like people. Quartz contributor Helen Edwards reports on how human biases get imported into AI—and how lawmakers and the tech industry are trying to course-correct.

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

Musk 500. CNBC’s Michael Sheetz reports this week that SpaceX could raise as much as $500 million in a new fundraising round that will value the company at $36 billion. We’ve been hearing rumors of this round for months now, and SpaceX has plenty of large capital expenditures in its future with its Starlink satellite constellation and the development of its next-generation Starship rocket. The timing feels carefully chosen—after the successful test flight of the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, but before its first flight with astronauts, or the widely anticipated move by the US military to decide the next set of national security launch contracts.

Coronavirus, seen from space. If you, like me, are now working from home in an effort to flatten the curve, you may feel cut off from the world. Luckily, we’ve got tons of sensors orbiting Earth and on the ground, and while that increasingly comprehensive panopticon may make you nervous, it also gives us a greater understanding of how the economy is changing as society faces off with Covid-19.

The last Dragon. Over the weekend, SpaceX launched the final cargo Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station under its original contract to ferry supplies to the orbiting lab. The company has a deal with the space agency to keep flying cargo through 2024, but it will use a version of its newer Crew Dragon spacecraft to perform those missions. It’s an important milestone in the evolution of space, as noted by some other stats on the mission—the Dragon spacecraft was reused for a third time, the Falcon 9 booster it flew on was making its second flight, and the company also made the 50th successful recovery of a reusable booster.

The end of the original space business? DirecTV, the leading US satellite television provider and one of the first truly successful space-augmented businesses, may be coming to a quiet end. Analysts predicted this after the company was purchased by AT&T in 2015, and now the company is no longer actively marketing the satellite TV service. Its main value for AT&T is a contract with the NFL to broadcast the full package of American football games. The service apparently faces too much competition from streaming services that people can access over the internet, without multi-year contracts or the hassle of installing a satellite dish. The move underscores how important competing with terrestrial alternatives will be for new attempts to deliver internet from orbit.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 38 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your takes on SLS sustainability, pictures of your favorite spacewalks, tips, and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.