Space Business: Higher Power

Astranis is making geostationary satellites exciting again

Dear readers,

Suggested Reading

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think.

Related Content

This week: The latest spin on a classic space business, Relativity scrubs its first launch, and Boeing wants to do what with the SLS!?

🚀 🚀 🚀

In the late 19th century, Pier 70 on the San Francisco Bay was a steelworks making mining equipment for the Comstock silver lode. It then became a shipyard, building massive naval vessels in World War I and World War II. It fell into disrepair until the city launched a rehab effort, starting with a massive facility for Uber’s self-driving car unit. When that shut down, the next bet on engineered prosperity moved in: Astranis, a company building and operating next-generation geostationary satellites.

When I stopped by the company’s headquarters this week, the scope of its history was on display. There was an old metal submarine just around the corner from a common room where a prototype of Astransis’ satellite is on display. The washing-machine sized spacecraft was surrounded by treats and decorations left over from a recent baby shower—a fitting atmosphere for a company about to launch its first satellite.

Astranis, founded in 2018 by CEO John Gedmark and CTO Ryan McLinko, plans to launch that spacecraft next month onboard a Falcon Heavy rocket. The company has a unique business model: Eschewing trendy architectures of massive, fast-moving low-Earth orbit constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink, it is instead disrupting the old-fashioned approach of putting a very large and expensive satellite in a very high altitude orbit, where it would remain in one location over the Earth. This had the advantage of simplicity: You could point your antennas right at the satellite without worrying about it moving. Astranis also builds spacecraft that operate in the same place, but at less cost and with more capability.

This straightforward pitch made Astranis the first space investment by the influential venture capital fund Andreessen Horowitz in 2018; it was valued by its investors at $1.4 billion during a 2021 capital raise. The company has been working through design and construction of its first commercial satellite, called Arcturus, which Gedmark says was ready a year ago and has been waiting for its rocket. The spacecraft is dedicated to one customer, Pacific Dataport, an internet service provider in Alaska, and will offer connection to an area of the world that, thanks to a low population and high latitude, hasn’t gotten much in the way of dedicated satellite coverage.

The idea of a dedicated geostationary satellite might not stand out in a world where Starlink and other large networks promise low-latency broadband from tens of thousands of dedicated spacecraft. But the costs of operating such a complex system are high. Astranis is betting that customers with specific, regional needs like Pacific Dataport, or two other announced customers—the country of Peru and Anuvu, a US airline internet provider—will choose a simpler model they have more control over.

The main downside is higher latency service thanks to the sheer distance between users and satellites. Astranis’ spacecraft will orbit about 30,000 kilometers farther away from someone on Earth than a Starlink or OneWeb satellite would.

Of course, the US military is intrigued. Many government satellites already operate in these high orbits, in part because the sheer remoteness protects them from enemy eavesdropping and attack. Now, though, rivals like China and Russia are using spacecraft that can inspect (and potentially attack) geostationary satellites. The US Space Force has asked Astranis to show that its spacecraft can do the same job as its billion-dollar spacecraft. If it can, a much cheaper geostationary satellite that can be quickly replaced might make rivals think twice about going to the trouble of attacking one.

The other appealing thing about Astranis’ spacecraft, per Gedmark, is their maneuverability. Most high-altitude satellites preserve their limited propellant to keep themselves in the right space, but the much smaller Astranis spacecraft has the ability to relocate 30 times, even to the other side of the planet. Combined with the company’s software-defined radio, which allows the spacecraft to operate on different radio frequencies as required, these satellites could be moved into place over a war zone like Ukraine, or over the site of a natural disaster, to provide emergency connectivity.

At its Pier 70 headquarters, Astranis has a facility capable of producing 24 satellites annually. The neighborhood was once known for building the machines to exploit a silver rush, and then ships for the first stages of modern global trade. If our next economic transformation comes from space, it’s fitting that some of that infrastructure is built there, too.

🌕🌖🌗

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

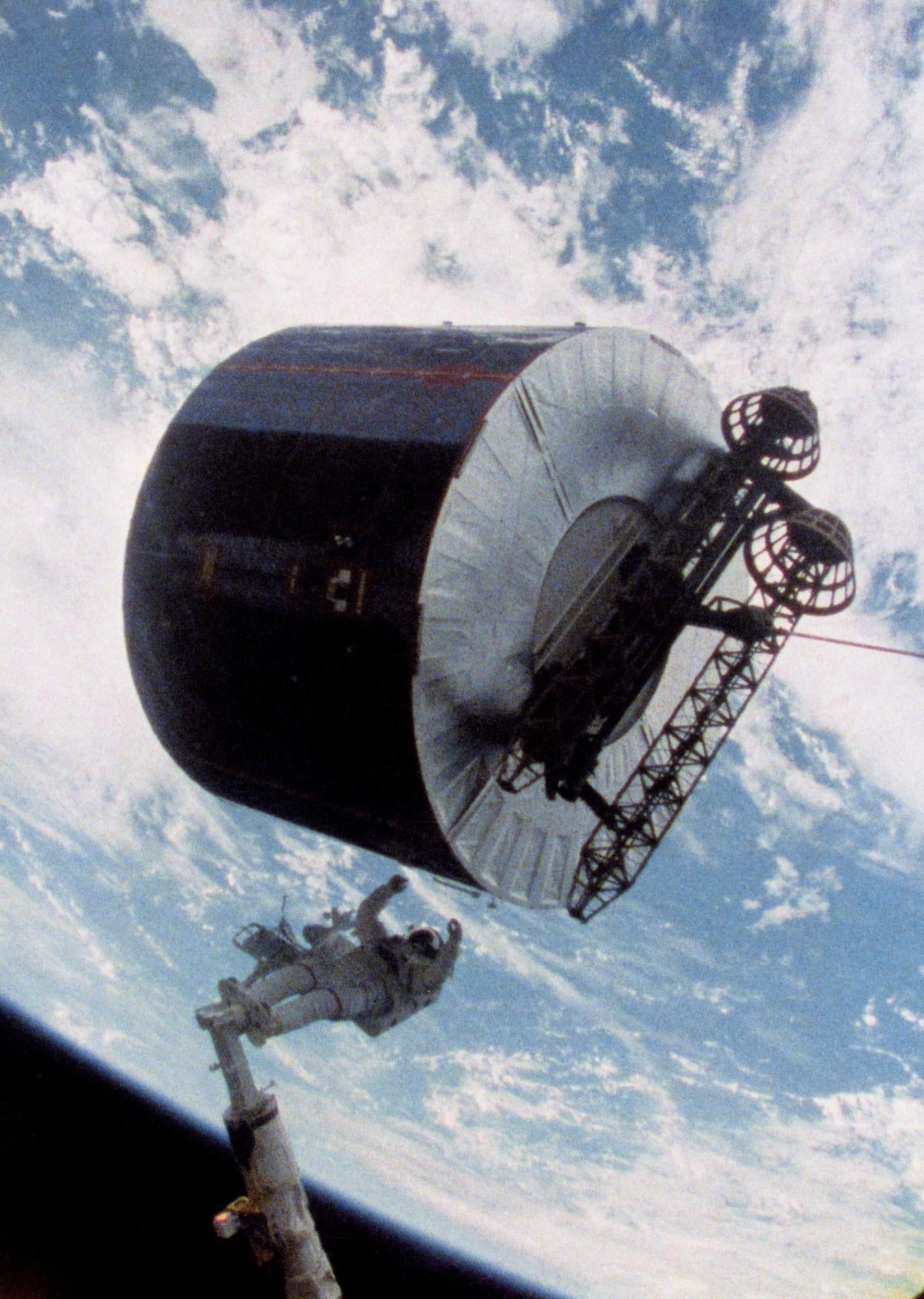

The first-ever geostationary satellite was launched by NASA in 1964. By the 1980s, the US Department of Defense was using several of them for communications. In 1985, US astronauts onboard Space Shuttle Discovery captured one of these satellites to repair it. Here, James van Hoften gives the repaired spacecraft a shove away from the shuttle.

SPACE DEBRIS

It’s all relative. Relativity Space scrubbed its first launch attempt for the Terran 1 rocket yesterday; it could fly again today. No private rocket maker has made it to orbit on the first try.

Japan’s H3 rocket self-destructs. Engineers terminated the second attempt at the debut flight of the Mitsubishi-built rocket after detecting an anomaly in the second stage’s electrical systems.

The International Space Station dodges a private satellite. The orbiting laboratory used thrusters on a docked spacecraft to avoid coming to close to an imaging satellite operated by Buenos Aires-based Satellogic.

The Middle East’s aspiring space powers. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have plans to spend billions on hardware that will enable their ambitions in space, but politics—at home, abroad, and in orbit—promise plenty of complications.

A new orbital clean-up firm gets funding. Starfish Space, founded by two former Blue Origin employees, raised $14 million to develop spacecraft to sercvice or dispose of satellites. Notably, its lead investor is the insurance giant Munich Re, which insures satellites and has a special interest in the tech to keep them in orbit.

Artemis 2 (barely) on track for 2024. NASA officials said that despite a few unexpected findings, their analysis of the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission puts the space agency on track to send four astronauts to orbit the Moon in November of next year.

Wonders never cease. Aviation Week’s Irene Klotz reports that Boeing wants to use its Space Launch System rocket to bid on US national security launch contracts. The SLS, the world’s most powerful operational rocket, costs about $2.8 billion per launch, making it difficult to believe that it will beat out cheaper vehicles like SpaceX’s Falcon rockets or ULA’s forthcoming Vulcan—unless the Pentagon is planning on a Moon base.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 171 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send the military use case for the SLS, your favorite pictures of manually-launched satellites, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].

Anomaly Report: Last week, the newsletter erroneously reported that the New Glenn is intended to be fully reusable; in fact, only its booster will be reused.