Space Business: Exquisite Ping

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: A sense of when you are, inside info on lunar landers, and private equity arrives in space.

🛰🛰🛰

With a launch this week, China has completed the build-out of a satellite system called BeiDou (Big Dipper in English), which will be used for navigation and synchronization.

If you’ve read the headlines, you might think this system is a “rival” or “challenge” to GPS, the US Global Positioning System. This framing doesn’t really capture what it means for China—or Russia (Glonass), or the European Union (Galileo), or Japan (Quasi-Zenith)—to operate its own sat nav system.

These services are vital to the modern economy. Beyond providing guidance to planes, cars, robots, and people, the signals are also used to provide precise timing for financial transactions and communication networks. And they are provided free of charge, using public protocols.

So why spend the billions required to launch a sat nav system if you can use them for free? The answer is geopolitics and national security. Military forces rely on sat nav most of all, and the original network was developed and is still operated by the US Air Force.

The creation of BeiDou was reportedly spurred by a 1996 incident when Chinese missiles, which at the time were guided by American GPS, went awry after being fired near Taiwan as warning shots. Chinese officials suspected US interference, and vowed to abandon their reliance on the American system.

There are similar, if more limited, concerns on a commercial level. Heiko Gerstung, an executive at Meinberg, a German manufacturer of precision timing devices, notes that GPS signals in Europe have been disrupted when American presidents visit. This is presumably an intentional action for security purposes, but a problem for anyone who relies on sat nav to do business.

“We sense a growing concern from our worldwide customers regarding their dependency on a US controlled infrastructure that could be switched off regionally at any point in time when it serves the interest of the operators of that system,” Gerstung says. “That has been and continues to be a very strong motivation for other nations to create or renovate their own GNSS constellations.”

That competition at least creates an incentive to improve what are effectively public utilities. But despite nationalistic rhetoric around these systems, non-military users are unlikely to be forced to choose among them. Apple’s iPhones already support Glonass, Galileo, and GPS services, and Qualcomm already makes chips that can use those services and BeiDou as well.

In the long term, the main economic question is who will make the lion’s share of the devices that use these systems. A US-China Economic and Security Review Commission report argues (pdf) that in the near term, more sat nav constellations will benefit American companies who already dominate the international market. But the authors believe China’s government is likely to use the same subsidies and favoritism lavished on other domestic industries to win market share at home and eventually around the world.

Davof Xu, an official at the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China who works on satellite navigation issues, is quoted in the report observing that market access in China is a “general not a particular problem.” In other words, BeiDou isn’t a challenge to GPS; China’s economic system is a challenge to American hegemony. But you already knew that.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude

In the late nineties and early 2000s, there was nothing better than showing off your GPS receiver, before such receivers were just built into ubiquitous pocket computers. In 1996, Gary Wagner was using GPS to precisely fertilize his fields. Nowadays, the GPS is built into the robots used to tend the farm.

👀 Read this 👀

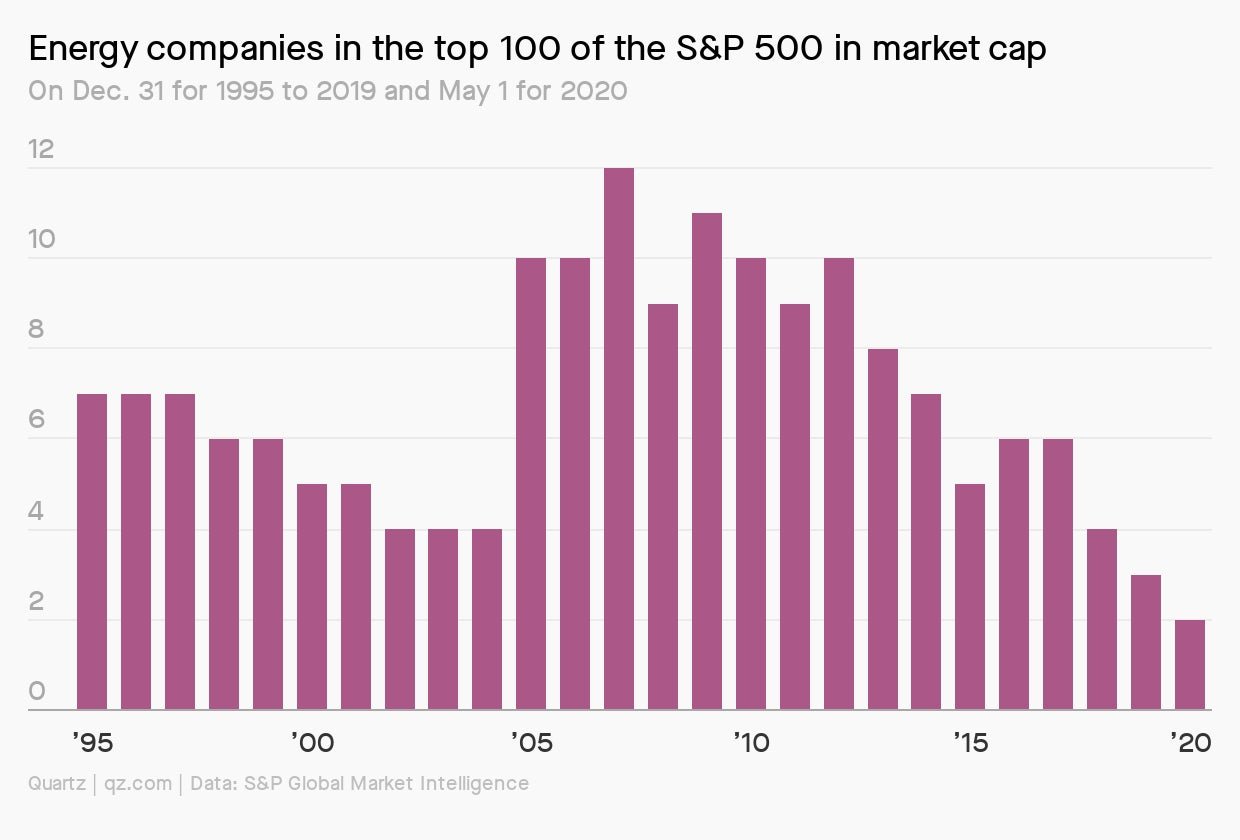

Battered by successive price crashes, facing mounting public scrutiny, and shoved aside by ascendant tech companies like Facebook and Google parent Alphabet, the power wielded by oil companies in the US is rapidly waning. In 2007, 12 of the 100 largest companies in the S&P 500 by market capitalization were oil companies. Today, there are just two.

Read more about the fall of companies like ExxonMobil from the S&P, and the challenges presented by the coronavirus pandemic, as part of our field guide on fossil fuels going bust.

🚀🚀🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

Inside information. New details have emerged about the May resignation of Doug Loverro, formerly the head of NASA’s human spaceflight programs. The Washington Post reports that his departure came when NASA officials became alarmed as Boeing sought to make changes to its plans to build a new lunar lander late in a contract competition. Those changes appeared to reflect inside information about the agency’s concerns, apparently from a conversation between Loverro and Boeing space executive Jim Chilton. Still, NASA officials say it did not affect the ultimate awarding of the lander contracts.

Constellation Class. Iridium, the satellite communications provider, has chosen start-up Relativity Space to launch replacement satellites starting in 2023. Iridium previously partnered with SpaceX to launch 75 satellites, a $3 billion “refresh” it completed in 2019. Those launches helped prove out SpaceX’s reusable rockets. Now, the company is tapping Relativity, a company that relies on 3D printing and boasts a large number of SpaceX alumni, to be its next ride to orbit. Relativity also said it had begun the process of setting up a West Coast launch site that will allow it to offer service to the orbits Iridum uses, expanding its potential customer base.

Middle Market Space. The private equity firm AE Industrial Partners is assembling a new space company to fit in the middle ground between start-ups and the big prime contractors. The firm acquired Deep Space Systems and ADCole Space, established makers of spacecraft components, and just this week announced the acquisition of Made in Space, a company attempting to manufacture unique goods in low-earth orbit. Fittingly, Made in Space’s flagship product are ultra-efficient fiber-optic cables made in microgravity, and Redwire’s name is a play on the most important part of an electrical system—”never cut the red wire.” The firm isn’t done snapping up space companies, either. “We’ll be very acquisitive going forward as well, we’re just getting started,” Redwire CEO Peter Cannito tells Quartz.

Remembering Moorman. US Air Force General Thomas Moorman, Jr. died on June 17. He played a major role in the development of US military space. Perhaps most importantly, he led a group that analyzed US space launch capabilities in 1994. The “Moorman Report” eventually became the framework for the military to ask private companies to “evolve” existing launchers into the Atlas V and Delta IV rockets, which led to the creation of a launch monopoly in the US, and the eventual rise of SpaceX. Quite something for someone born seventeen years before the first orbital rocket was launched.

Other stuff is hard, too. Sometimes space world can get a little too infatuated with its own unique challenges, which is why this SpaceNews essay on looking for solutions in other sectors feels so refreshing.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 54 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your conspiracy theories about satellite navigation systems, the space companies you think make the best acquisitions, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].