Cooper Oil & Gas is a true mom-and-pop fossil fuel shop, launched in 1979 in Fort Worth, Texas. Glenn Cooper, inspired by an uncle in the industry, quit commercial real estate to work the rigs; his wife, Belinda, left her job as a hospital lab technician to run the company’s books.

Glenn “took a leap of faith in himself and my mother,” their daughter Cye said. “They started from zero and drilled all the wells themselves.”

Cye grew up on oilfields, and went on to study petroleum engineering and work for major drillers like Chevron and EOG Resources. Eventually, she convinced her dad to hand her the reins. Today, the company operates 300 wells.

Over the last decade, she’s steered her family business through price crashes and pay cuts, motivated by the challenge and thrill of chasing what she calls “one of the most rewarding dollars you’ll ever put in your pocket.” She’s clear-eyed about the oil market’s nature to cycle through booms and busts. But nothing could have prepared her for the coronavirus pandemic.

At the beginning of 2020, the price of West Texas Intermediate, the US oil benchmark, was around $60 per barrel, just above where it had hovered for the last few years. It began to slip in late January, as news spread of a mysterious virus. In mid-March, amid cancelled flights and cities on lockdown, after the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic and Saudi Arabia and Russia initiated a game of brinkmanship over production cuts, the WTI fell 29% in a week, its biggest one-week drop since September 11, 2001. From April 19 to 20, as surplus oil filled the world’s storage capacity, it took a record one-day plunge, falling 515% to go briefly negative for the first time ever.

The impact on oil companies, from the biggest supermajors to independents like Cooper, was swift and devastating. In a matter of weeks, the world’s most valuable commodity had become practically impossible to sell. At least 500 drilling rigs in the US have been shut down, pushing the nation’s total to its lowest level on record. Most of the global majors posted Q1 earnings far below 2019 levels; some have plans to cut thousands of employees. Several smaller companies have already filed for bankruptcy; analysts project hundreds more could follow over the next year even if prices rebound somewhat. Texas shed a record 26,300 oil and gas jobs in April alone, and could lose up to 100,000—one-third of its workforce in the industry—by the end of the year.

Cye, whose surname is now Wagner, watched this all unfold from her other role as chair of the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers. She had never laid anyone off before. But with her business in survival mode, she had to let several of her two dozen employees go.

“No one is coming through unscathed,” she said. “We understand we’re in a cyclical industry. We’re used to dealing with it. But this was not that. This was monumental and historic. The market was telling us that what we do is worthless.”

The price of WTI has since recovered a bit, to around $30 per barrel as of early June. But the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects global oil demand to be 10% lower this year than last, a record drop. McKinsey projects that prices could return to pre-pandemic levels by 2022. Or 2024. Or never.

That doesn’t mean the coronavirus pandemic is the death knell of the oil and gas industry. Although renewable energy has made some remarkable gains in recent months (including surpassing coal in the US electricity mix for the first time), the world’s vehicles and power plants will still mostly run on fossil fuels for years or decades to come. But building on social anxiety about climate change and increasing skepticism among investors that fossil fuels are worth the risk, it’s the most visceral preview yet of an existential crisis for the industry. And it will force every company to reckon with what it will take to survive.

For small producers, attempting to pull through bankruptcy and finding it increasingly difficult to raise capital, the pandemic may end a 150-year-old Wild West mentality that prioritized accumulating assets regardless of profitability, tolerated levels of debt well beyond any other industry, and assumed a boom would follow every bust. And for multinational majors, it has laid bare the competing schools of thought about how to make money as a modern energy company. For some, the crisis is proof of the need to accelerate a transition away from fossil fuels. For others, it’s a chance to strengthen their grip and ride oil, bucking and snorting, into the sunset.

“There are so many more variables at play in this particular downturn, it’s difficult to predict what the recovery will look like,” Wagner said. “But I don’t think oil and gas will ever look the same.”

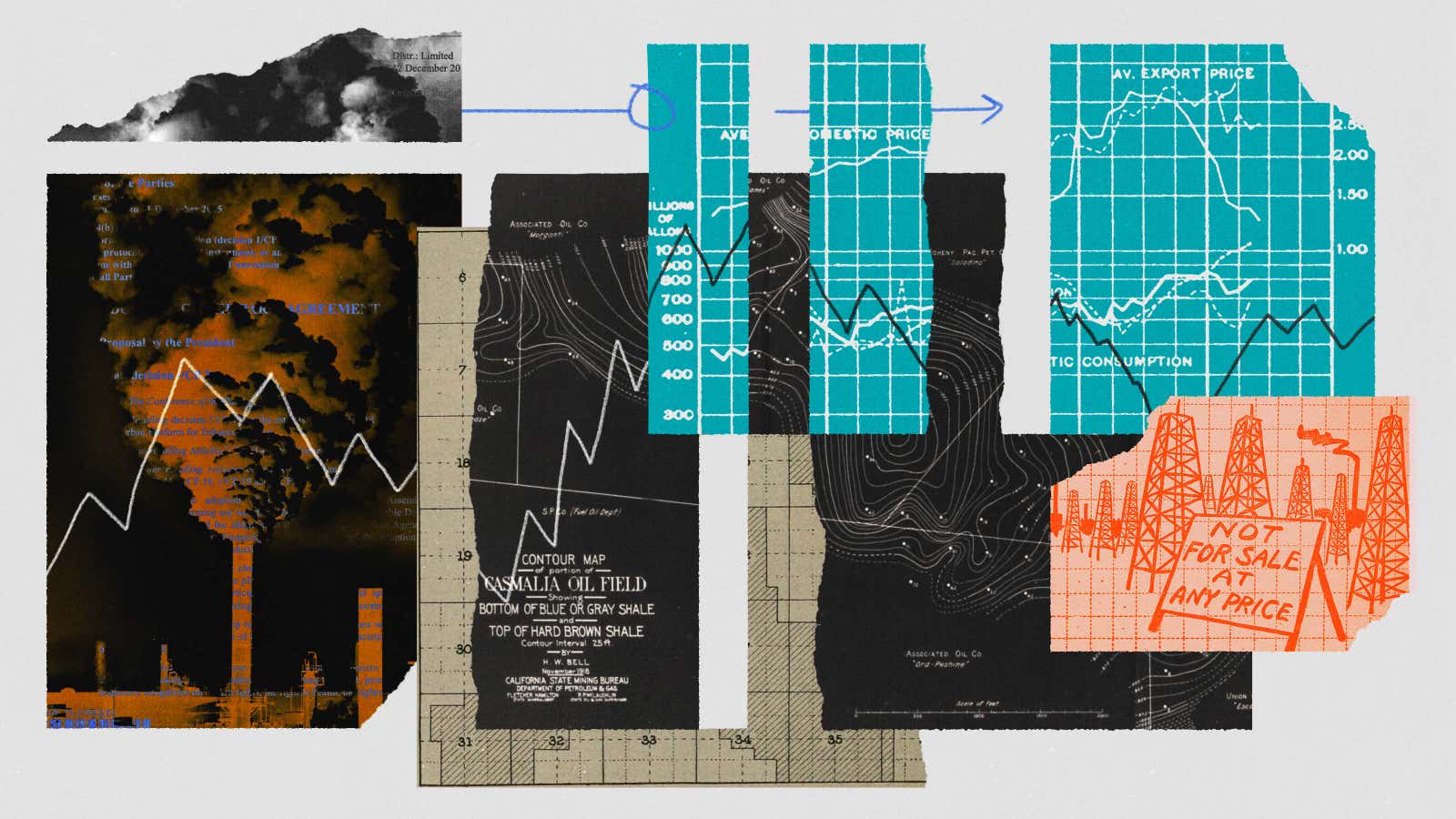

The first boom

It wasn’t until the 1800s that Americans rediscovered the substance that would transform the modern world. A thirst for light turned oil into a global industry virtually overnight. And it ignited the boom-and-bust cycle that continues to this day.

Lamps in 1850 burned fuel that was either expensive or dangerous: exploding camphene (a mix of alcohol and turpentine), whale oil, beef tallow, or sooty “coal oil.” After sunset, most people were condemned to the dark. The discovery of “rock oil” in Pennsylvania’s Appalachian mountains gave the world kerosene, an inexpensive distillate of petroleum, which in turn gave the average American the luxury to live and work after dark.

It started in Titusville, a small town in Pennsylvania, in 1859. Edwin Drake struck the world’s first successful oil well after his steam-powered drill punched into a reservoir 69 feet down. Soon, thousands of prospectors had erected crude wooden rigs to drill. Fortunes were made in a flash—and lost just as quickly when the oil inevitably gave out. One Titusville parcel sold for $2 million in 1865 ($32 million in today’s dollars), according to Daniel Yergin, the Pulitzer-prize winning author of The Prize, on the origins of the oil industry. The same piece of land was auctioned for $4.37 about a decade later.

This rapid expansion and contraction has set the backdrop for the fossil fuel industry ever since. Prices topped $16 per barrel in 1859 and then plunged to 49 cents just two years later. (Even drinking water was more expensive.) This chaotic era was defined by “wildcatters” prospecting new wells, flooding the market with oil, and going belly up when prices plunged. But the market was about to come under the thumb of one man, John D. Rockefeller, who despised the “mining camp” mentality of the oil industry, and turned the industry into the domain of massive multinational corporations.

For a time, his firm, Standard Oil, appeared to tame the market. It quickly rose from obscurity to force out competitors, often through unsavory tactics, and acquired most of the oil refining capacity in the US. By 1899, it controlled the vast majority of the oil sold in the US, and set its eyes overseas where rivals were just glimpsing the industry’s potential.

International demand for oil seemed insatiable: kerosene, gasoline, natural gas, and later every manner of petrochemical soon formed the foundation of the industrial economy, displacing almost every other fuel beside coal.

But the perils of the choice were always clear. Oil had to be found, pumped, refined, and shipped a world away. The only way to keep the oil flowing was to size up. Truly global companies were a rarity in the late 1800s, yet the global appetite for oil demanded massive companies to match.

Standard Oil was the first. But demand soon eclipsed even Standard Oil’s ability to supply or control it. By the early 1900s, foreign rivals were proliferating. Dynamite mogul Alfred Nobel joined his brothers to create Russia’s largest oil company in the remote Baku oil fields. A small London importing firm in the city’s busy loading docks became Shell Oil. In Sumatra, a colonial entrepreneur built Royal Dutch drilling in what is now the jungles of Indonesia.

The industry Rockefeller thought he had tamed erupted into chaos again. Technological innovation was constantly upending the industry. Each new development—advanced drilling rigs, better refineries, longer pipelines, bigger tankers, and later offshore platforms—favored players who could do it faster or cheaper.

This next round of oil innovation and exploration set the stage for modern oil companies, and today’s struggles. The automobile sparked unprecedented demand and new discoveries of oil. Within a decade, America became an oil-importing nation for the first time. Never before had oil consumption risen so much, so fast. The post World War II economic expansion ran on oil. Between 1945 and 1970, consumption rose six-fold, barely breaking stride during subsequent recessions.

Oil companies raced to keep pace. In 1938, offshore oil production began off Louisiana’s marshy coast. Chevron hit oil in Saudi Arabia, still the largest discovery in history, the same year. Oil companies needed billions of dollars to pump oil in some of the most far-flung regions of the world and transport it to markets in Europe, Asia, and North America. Geopolitics reoriented themselves around strategic control of oil reserves and shipping lanes. Exxon, Texaco, Mobil, British Petroleum, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell, Arco, and Gulf Oil achieved unprecedented size and influence.

By the end of the twentieth century, however, these firms found that the days of easy oil were behind them. National governments, which had grown dependent on oil revenue, came to resent oil majors’ power. Until the 1950s, international oil majors could effectively set global prices, even if low prices might threaten a country’s budget or stability. Tension over this control burst into the open in 1960 when Standard Oil of New Jersey unilaterally enacted a price cut. Major oil exporters countries held an emergency meeting in Baghdad, culminating in the creation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Its five founding members—Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Kuwait, Iraq, and Iran—represented more than 80% of the world’s oil production; over time, the cartel extended its grip over the world’s oil supply.

Today, national oil companies control more than 90% of the world’s known oil reserves—valued at more than $3 trillion—up from just 10% in the 1970s. Yet for international oil companies, the cost of extracting oil kept going up. Exporting nations controlled the cheapest sources of oil, while the biggest finds from the 20th century were being exhausted. Billions of dollars were needed just to keep up production with global demand.

To survive, six “supermajors” emerged from dozens of acquisitions and consolidation. BP bought Amoco and then Arco for $75 billion. Exxon and Mobil merged into ExxonMobil. And so on for Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Total, and Royal Dutch Shell. By 2013, the supermajors were spending at least $100 billion per year on exploration and production.

Yet something was coming that would change everything. In the US, the cost of conventional oil remained high: $80 to $100 per barrel. But drillers were starting to deploy a new technology called fracking. By drilling horizontal wells into underground shale formations, and injecting water, sand, and chemicals to break them up, American oil firms could suddenly extract far more oil and gas for much less than before. It was the beginning of a new oil rush.

The last boom?

In 2000, shale gas made up only 1.6% of US gas production. By 2010, thanks to a combination of government-sponsored technological advances, high natural gas prices, and investment from entrepreneurs like Continental Resources’ Harold Hamm, it was 23%.

Oil followed suit as fracking opened up vast new areas of the country to drilling. US crude production nearly doubled from 2005 to 2015, driven in large part by shale oil; in the same period, the country’s oil imports fell 62%. The number of rigs skyrocketed and by late 2014 industry employment was above 650,000, its highest level in decades.

To cover the high costs of exploration and drilling, banks and private equity funds pumped tens of billions of dollars of debt into the industry. There wasn’t much concern for whether individual companies were generating cash. With the WTI north of $100, it seemed worth the risk to simply grow as much as possible.

By 2013, thanks to fracking, the US reclaimed the mantle of world’s top oil producer, which it had ceded to Saudi Arabia for more than a decade. Fracking hubs like Williston, North Dakota became overnight boomtowns. Hamm became a billionaire.

Karr Ingham, an economist with TAEP, described the US shale industry’s attitude during the early 2010s as a game of musical chairs.

“You roll along, and you’re drilling a lot of wells, and you’re borrowing a lot of money, and you just hope that the merry-go-round doesn’t stop before you can get it under control,” he said. “Everything is good until the music stops. Well, the music stopped in a big way, and in a hurry.”

In late 2014, with US oil production still soaring, global oil supply began to exceed demand. The WTI price started to tumble below the point where many oil companies could turn a profit, and the boom turned to bust. Oil and gas share prices, which had closely tracked the S&P 500 for decades, veered downhill. Investors got burned, and the industry entered a prolonged contraction.

The low oil prices squeezed profit margins. Some firms, especially smaller independents, began to hemorrhage cash. “As far as I can tell fracking has completely destroyed the business model of the entire fossil fuel industry,” says Clark Williams-Derry, of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

“Shale plays used to be very popular with investors and banks,” said Elizabeth Gerbel, CEO of Houston-based oil consultancy EAG Services. “But people lost a lot of money in 2015-17, and came out of it demanding that shale companies start to operate like a normal business.”

Meanwhile, just as the shale boom was winding down, representatives from most of the world’s governments met in an old airport outside of Paris in December 2015 to hammer out a wide-reaching agreement on climate change. The agreement aims to limit global warming to 1.5-2 degrees C (2.7-3.6 F) above pre-industrial levels. To reach the more ambitious end of that spectrum, global emissions need to decline 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, according to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Energy researchers have proposed countless ways of reaching that goal. All entail some combination of using far less fossil fuels and offsetting or capturing the emissions from those we do use.

Although the agreement didn’t make specific demands of oil companies, it codified a range of carbon-cutting policies by countries around the world, which amounted to an unprecedented threat to the long-term financial viability of the fossil industry’s business model. And it drew attention to the industry’s sordid history of denying the existence of climate change and spending millions to blockade climate policies. That led some oil companies to acknowledge the need to reduce carbon emissions, in their public statements if not necessarily in their actions.

A fissure quickly emerged between European and American companies. The UK’s BP, the Netherlands’ Shell, Italy’s Eni, and France’s Total (along with state-owned Saudi Aramco), some of which had already dabbled in renewables, were among the first to join a coalition in support of the agreement; the US’s ExxonMobil and Chevron sat out. A year later, most of the same European companies launched an investment fund for renewables, again without their American counterparts.

The fissure has since widened.

A June analysis by Rystad Energy found that oil majors plan to spend more than $80 billion on renewable energy over the next five years, of which all but a few hundred million will be from European companies, with Shell, Total, and Norway’s Equinor leading the pack. This spring, BP and others announced goals to reach net zero emissions by 2050, with intermediate targets along the way

Exxon, meanwhile, which generated $255 billion in revenue in 2019, committed last year to spend just $100 million annually on low-carbon tech, with a focus not on renewables but on carbon capture technology that would facilitate the continued use of fossil fuels but with a lower greenhouse footprint. In March, the company’s CEO dismissed his competitors’ climate targets as “a beauty match.”

According to recent research by the London School of Economics and others, even the most ambitious of these goals doesn’t put the world on track to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees C, the target agreed to in Paris. And even the most ambitious clean energy investments amount to no more than 4% of any company’s total capital expenditures, according to the Carbon Disclosure Project. The rest is poured first into oil and gas exploration and production (what the industry calls “upstream” activity) and second into “downstream” activities like refining and selling gasoline, and processing petrochemicals.

Still, the trans-Atlantic divide points to a fundamental divergence of opinion about where the profits of the future will be made.

“American oil CEOs have generally been rosy about the future growth of oil and gas,” said Ben Ratner, a senior director for oil and gas at the Environmental Defense Fund. “The Europeans have expressed more recognition of the limitations, in particular that the real growth areas are going to be in clean energy.”

From a strictly bottom-line perspective, there’s plenty of reason to be bullish about clean energy. Solar is by far the fastest growing energy source, having increased 46-fold in the US between 2008 and 2018. According to Bloomberg, in most of the world, solar and wind are now the least expensive forms of new energy and are expected to attract trillions of dollars in investment over the coming decades. In 2019, an S&P index of renewable energy company shares grew 49%, outperforming the S&P 500 by 20 points; the oil and gas index fell 11%. Electric vehicles, which today make up less than 3% of total vehicle sales, are projected to make up more than half the market by 2040.

But for now, Ratner said, “they’re all still fundamentally oil and gas companies at their core.”

The bust to end all busts

When the pandemic hit, the oil industry was suddenly faced with an unprecedented drop in demand, and the possibility that some common uses of oil—airplane fuel, for example—might take years to return to pre-crisis levels, if they ever do.

One of the first ways oil companies big and small responded was to cut their capital spending. Industry-wide, those cuts add up to nearly $250 billion, according to IEA, with the majority coming off of budgets for exploration and production. European majors left their clean energy spending mostly untouched.

In a series of conference calls in April and May, CEOs hinted at their position on a key philosophical question underlying the trans-Atlantic fissure: For the Americans, the pandemic is a bump in the road; for the Europeans, it’s a signal that peak oil demand may be closer than they thought—or even in the rearview mirror.

“There is an energy transition underway that may even pick up speed in the recovery phase of the crisis,” said Shell CEO Ben van Beurden, “and we want to be well-positioned for it.” When asked whether the pandemic increased the chances of peak oil arriving this decade, he said the likelihood “has indeed gone up.” BP CEO Bernard Looney said he sees “a real possibility that some of [the pandemic-related demand destruction] will stick.”

That skepticism is reflected in BP’s new oil price outlook, released on June 15, in which the company revised its pre-Covid oil price projection for the next few decades down by nearly a third, and said that it doesn’t expect prices to return to pre-crisis levels.

The pandemic revealed “increasing uncertainty surrounding the future demand for oil,” said van Beurden, coupled with “increasing attractiveness of stable returns from some renewables.”

Indeed, although the pandemic also triggered deep job losses for the clean energy industry, it also provided an opening for renewables to surge even as oil and gas flailed. With electricity demand down, power companies have looked for the cheapest way to serve their customers: Wind and energy fit the bill. The US is on track to get one-fifth of its power from renewable sources this year, a record, and the first time ever renewables will beat out coal. In Europe, utilities that relied on renewables suffered smaller losses than their fossil-reliant peers.

But meanwhile, Exxon CEO Darren Woods said that “despite the current volatility and near-term uncertainty, the long-term fundamentals that drive our business remain strong and unchanged.” Chevron CEO Michael Wirth was more explicit: “The world is not ready to transition to another source of energy in large part anytime soon. And so the resumption of economic growth will require the sources of energy that we know today and that fuel the world today. And there will be a need for what we do.”

Since the initial oil price crash, demand and supply have started to even out. Global production fell about 13% between Q1 and Q2, due to a combination of voluntary reductions by companies and production cuts mandated by OPEC. Demand, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis, bottomed out in mid-April and has been creeping back as lockdowns lift, although the annual total will still be far below last year’s. As a result, the WTI price has been inching upward—although a rapid return to drilling, or a second wave of Covid cases, could easily send it spiraling down again. As a May report from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies put it, the process of rebalancing the oil market will be “slow, with many bumps in the road ahead.”

As the oil majors travel down that road, their expectations for the future can be seen in how they treat their upstream business, said Ellen Wald, an energy historian and senior fellow on oil and gas at the Atlantic Council. Will they reinvest in exploration and production or, as Shell has done recently, put parts of it up for sale?

“When you sell upstream assets, it makes your books look better. It can pop up your stock price,” she said. “But, if oil goes back over $80, you’re out those assets. Shell may think that oil is never going to go that high, so why bother? Whereas Exxon may have a different opinion.”

Regardless of where they fall on this question, none of the majors is facing an existential threat from the pandemic. In the short term, a lower oil price can even be beneficial for them: It can drive up demand and the profit margin for downstream products like plastics and fertilizer, said Ed Hirs, an energy economist at the University of Houston.

“Going forward, the majors are going to be fine. They’re not going to close up shop anytime soon,” Hirs said. “They think in terms of decades, and they think in terms of an integrated supply chain: They own all the way from the wellhead to the gas station pump. And are we ever completely gonna go away from using oil? You know, not in our lifetimes.”

Still, it’s clear that the European companies are looking for an exit, now more than ever.

“This crisis is showing that the runway is a lot shorter than many of them had thought,” said Andrew Logan, senior director for oil and gas at the sustainable investment nonprofit Ceres. “There aren’t that many examples of any industry winding down really slowly. Companies tend to assume they have more time than they do.”

For shale companies, which are among the most expensive and vulnerable of the world’s oil plays, that runway may be even shorter (although individual shale CEOs are often able to grab hold of a golden parachute).

A key difference between the 2015 bust and now is demand: Back then, there was still plenty of it. Now it’s decimated, and it’s not clear how much will come back. That risk will make access to capital, already tight before the pandemic, even tighter.

Another lesson of the 2015 bust, now being reinforced by the pandemic, is that companies should be able to do more with less even in good times.

“By the time our economy gets back to demanding oil at levels that are anywhere close to what they used to be, a lot of production will have been sidelined. That’s a recipe for a rapid price increase, and companies will get right back to work,” TAEP economist Ingham said. “But we know that it won’t take as many people or as many rigs. We’ve watched these cycles play out. You lose them in a hurry, and when companies get into the kind of cost-cutting mode that they’re in right now, which I’ve never seen before, they’re not going to be adding employees back any time soon.”

In addition to being leaner, shale companies will need to be more tactical about where they operate, EAG’s Gerbel said.

“Before 2015, companies were drilling everywhere. They were in Texas, Oklahoma, the Gulf, all over the place,” she said. “Now you’ll start to see companies focusing their operations on areas where they understand how the geology works and what the results of their drilling will be, so that if they put investment into a well they’re quite certain what the outcome will look like.”

To Cye Wagner, the best analogy for the current moment is the dotcom bubble. A lot of money went into half-baked ventures and was never seen again. But as the internet matured, and investors became more exacting, companies that stayed focused could still make a killing.

“The lesson you learn from history is that it’s not what you do when the price is low,” she said. “It’s what you do when it’s high. How do you manage your resources? Because you’re going to need them when it’s low—and it’s not if it goes low, it’s when.”