Space Business: Dust hunters

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: China on the moon, managing a year of stress, and an old rocket comes home for the holidays.

🚀 🚀 🚀

For the second year in a row, China has landed an ambitious robotic explorer on the moon.

This mission, called Chang’e 5, will make the first attempt to return samples of lunar soil to earth since Russian robots and NASA’s crewed Apollo missions did so more than four decades ago. But the physics underlying these missions hasn’t changed—it still requires a vehicle with a total mass of 870 metric tons to bring just 2 kilograms of rock back to earth, while carrying a few other scientific instruments along for the ride.

Scientifically, the trip to an unexplored zone promises to yield new information about the moon’s evolution. Technologically, a successful sample return will demonstrate China’s capacity for sophisticated systems engineering. Politically, Chang’e 5 will ramp up the pressure on the US to deliver its own prestige-enhancing moon mission.

The lunar renaissance of recent years, driven by the confirmation of water there in 2008, will once again test the viability of different approaches to spaceflight, but in a different way than during the Cold War. Rather than a battle of socialism versus capitalism, this time around, the space race will pit America’s open and fractious space program against China’s centralized approach.

The difference is strategic: China’s Chang’e 5 mission is, you guessed, the fifth mission in a steady progression of lunar exploration by the China National Space Administration. The country’s space strategy is planned in careful five-year chunks, and the path ahead includes another sample return in 2024 and a polar survey in 2030 before Chang’e 8, which is designed to lay the groundwork for a crewed lunar research base in 2036.

The US took a similar approach in the 1960s, sending a steady series of surveyor satellites and probes before the eventual moon landing. Today, though, NASA’s Artemis program looks less like a single unified effort and more like an It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World-style race back to the moon—and I mean that as a compliment.

The US will be paying as many as four private companies to launch six different lunar missions over the next three years, using multiple spacecraft and landers to carry a variety of instruments designed by NASA and universities, including an ice-hunting drill and a rover called VIPER. A dozen other firms are waiting in the wings to compete for future moon missions, and today NASA will announce companies that have been selected to collect lunar samples for a future return mission.

And that’s just the start. The eventual return of US astronauts to the moon is likely to include spacecraft built by Boeing, SpaceX, United Launch Alliance, and Maxar, and they could be delivered to their destination in a lander built by one of three competing consortiums that include firms like Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, and Dynetics. And companies in Europe, Canada, India, and Japan are already participating in various stages of what is beginning to seem like a project that’s much bigger than NASA alone.

These companies aren’t just competing against each other to produce the best design for the dollar. They’ll also compete politically to influence the architecture and timing of the lunar mission, as part of a broad debate that will also include NASA officials, lawmakers, scientists, and occasionally public opinion. We have to imagine some similar battle of interests taking place behind the scenes in China, but outsiders don’t know the true stakes or how they are ultimately resolved.

Getting all the different contributors to the US lunar return on the same page can seem daunting compared to the efficiency displayed by China’s moon march. That’s sort of the point: The US knows it can mobilize a national effort to put people on the moon. Whether it can create a lunar economy is a much more interesting question.

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

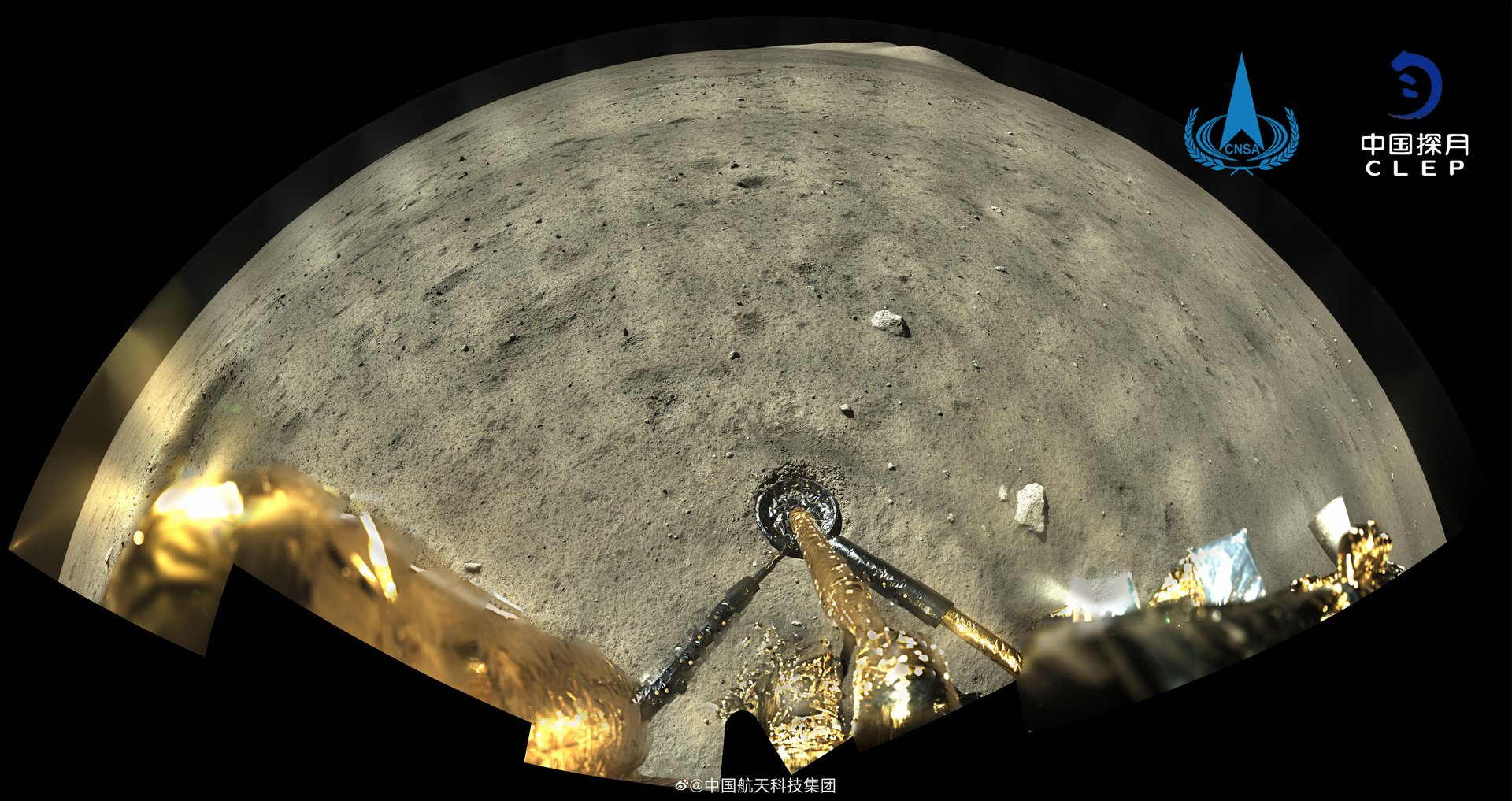

China’s national space agency released this panoramic image snapped by a camera onboard the Chang’e 5 lander after it touched down.

Don’t miss the video of the landing itself, either.

👀 Read this 👀

It’s been a stressful year. *laughs hysterically* Even when tension isn’t specific to work, it shows up in our workplaces. If not channeled constructively, it takes a toll on relationships, productivity, morale, and mental health.

Supporting team cohesion during times of turmoil falls to managers who may not have ever planned or trained for the task. Our recent workshop on how to manage teams through tension brought together four executives with a wealth of experience and advice to share. You can watch the full replay as part of our field guide to leading through change. Workplaces have gone through enormous change. It’s time the management handbook got an update as well.

🛰🛰🛰

Hello again. Astronomers have been tracking a new object that emerged in the solar system in 2020—or have they? Researchers now believe the object is in fact part of a rocket that launched a failed NASA moon mission in 1966. Ever since, it’s been orbiting the sun, and now it is returning for a close path around earth. Scientists hope observations taken as it passes near the planet this week will confirm their theory of the rocket’s return.

Signal-to-noise. One of the big factors in the success of the new generation of low-earth orbit satellite constellations is the cost of their antennas. Unlike traditional satellites, which effectively remain in one spot above the earth, the new networks require dishes that can track moving spacecraft. Some critics argue that SpaceX is losing as much as $2,000 on each dish purchased by users of its Starlink network. The antenna is clearly not cheap, as this fascinating teardown shows. The dish could be a millstone dragging down the whole business, or merely a loss leader, with future costs reduced through higher-volume manufacturing and long-term amortization. It’s definitely an issue to watch.

China has satellite aspirations, too. China’s military has completed the build-out of a remote-sensing satellite constellation called Yaogan-30. According to one independent analysis, the 21 satellite network appears to provide China with the ability to fly sensors over Taiwan and nearby areas of the Pacific every thirty minutes, if not more often, the highest revisit rate of any known satellite system. China isn’t stopping there; according to an interview with a Chinese researcher cited in the analysis, the next steps are even larger constellations to watch territories along China’s Belt and Road network, and eventually the world. The surveillance space race, at least, is in full effect.

Russian re-org. Roscosmos chief Dmitry Rogozin, meanwhile, appears to be purging the leadership of various troubled ground infrastructure projects. A particular area of concern appears to be the expansion of the Vostochny spaceport, intended to reduce dependence on the Baikonor Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, where much Russian launch activity still takes place.

RIP. The science fiction author and space exploration advocate Ben Bova passed away on Nov. 29 at the age of 88. Quartz excerpted a 1984 essay he wrote envisioning a “tricentennial celebration” on the moon in 2076 that remains insightful to this day.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 76 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your favored framework for lunar dispute resolution, cost estimates for LEO constellation ground stations, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].