Science fiction is one of the great drivers of space exploration, helping inspire Robert Goddard to invent liquid-fueled rockets and providing a catalyst for Ronald Reagan to launch the Strategic Defense Initiative.

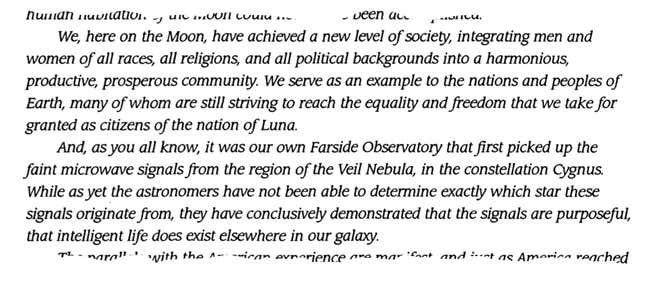

At a NASA lunar colonization symposium held in 1984, the science fiction writer and then-president of the National Space Institute Ben Bova delivered a fictionalized speech (pdf), an “address given at a Tricentennial Celebration, 4th July 2076” held at Luna City—a future moon colony.

Here are a few telling excerpts about what we got right then—and what we might be getting wrong, now.

You have to love the space timelines of yesteryear: Bova is envisioning not just a return to the moon by 2001—seventeen years after he writes—but also a full scale secession and the founding of a new moon nation over the next seventy-five years.

Bova imagines a female astronaut taking the second first steps on the moon. Today, twelve of the thirty-eight American astronauts are women; in 2001, the ratio was significantly worse.

He also kicks off a metaphor still common today, which emphasizes the parallels between exploration of the moon and the exploration of the western hemisphere by Europe.

Aside from the most common objection to this analogy—the “New World” had an ecosystem to support human life—note that the promise here is that humans on the moon will find surprising new resources. Yet it does not seem likely that we will be surprised on the moon with resources as useful as the humble potato. Today’s moon schemes, benefitting from more detailed information, tend to focus on the nuts and bolts.

The intervening decades have essentially flipped the order of the first paragraph: The first settlers are coming for water, and it is only with that precious resource that anything like a factory in orbit near the earth might be possible.

The bigger levels up in the lunar economy—exporting energy, minerals or even finished goods—remain science fiction to this day. The clearest economic case for the moon is to support space activity near-earth, which Bova correctly predicted as satellites of various kinds, and broader exploration of the solar system.

In the years ahead, the manufacture of some goods may be feasible in low-earth orbit. But as experiments with biologic pharmaceuticals and ultra-precise electronic components like fiberoptics continue, they will rely on earth-bound resources.

Is it weird that I’m more cynical about Bova’s vision of political utopia on the moon than the possibility of finding extra-terrestrial life in the universe? Astronomers, at least, are bullish about the idea that radio observatories on the moon’s far side could yield important information about the history of the universe.

But, politically speaking, the moon still seems likely to import earth-bound political problems before it exports a post-scarcity future.