Space Business: Radar love

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: SAR stars, moon rocks returned, and more delays in the hunt for threatening asteroids.

This will be the final edition of Space Business in 2020. Thank you for reading, and see you in the new year!

🚀 🚀 🚀

A little shop in San Francisco is now offering what it says is the highest-resolution space radar imagery on the market.

Capella Space released the first images taken by one of its orbiting spacecraft, demonstrating the ability to capture imagery at a resolution of 50 cm per pixel—the legal limit imposed by US regulators to prevent too-detailed reconnaissance imagery from falling into the wrong hands.

Founded in 2016, the company has launched two satellites that beam radio energy at the Earth from orbit and decode its reflection back with a novel antenna design. After its first prototype was tested in orbit, Capella had to redesign the second satellite, launched earlier this year, to reach this level of detail. Over the next six months, the company plans to launch six more satellites and begin selling the data they collect worldwide.

“It’s business time,” CEO Payaam Banazadeh says. The company has 40 re-selling partners around the world ready to begin offering its imagery, along with largely undisclosed pilot customers working directly with Capella.

One of them is the US government, in the form of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), which collaborated with Capella after encountering Banazadeh and other founders at a Stanford University hackathon. In 2017, the company received a DIU contract to develop a prototype, inspired by growing concerns over North Korea’s nuclear missile program.

The best way to watch for the threat of pop-up missile launchers is with space radar, but in 2007 the government estimated the cost of such a system would fall somewhere between $27 billion and $94 billion. That was before the rise of small satellites and venture-backed space firms; in comparison, Capella has raised about $84 million.

“For government to get where we are today, they would have spent money to study the problem and at the end of that probably decide we shouldn’t move forward,” Banazadeh says. “With that study money, we’ve already built that capability.”

To be sure, Capella doesn’t yet have the full-on constant surveillance capability imagined by the government. But the first seven operational satellites will still be able to keep tabs on a wide swath of the planet, and the company imagines a constellation of 36 spacecraft could eventually provide broader coverage at costs an order of magnitude below a traditional system.

“DoD partners have been very impressed with the commercial availability of day, night, and all-weather imaging services,” Air Force general Steven “Bucky” Butow told Quartz. “Equally impressive is the low signal to noise ratio provided by such a compact and relatively inexpensive platform. Capella’s work over the past few years has shown the art of the possible with small satellite SAR—especially with novel antenna design—and drastically reducing the cost of building a satellite and launching it with this type of capability.”

A next step for Capella will be expanding its customer base to include users who don’t typically work with radar data, which is more complex to employ than visual-wavelength imagery produced by many remote-sensing companies, but arguably more robust. Because of the cost of the imagery, there has not been a large data set available for companies specializing in machine-learning analysis to develop SAR techniques. Capella plans to collaborate with these users to make the insights from their product more valuable in multiple sectors.

Competition among private space radar providers is heating up—notably, the Finnish company ICEYE already operates three high-resolution SAR satellites; the Japanese firm Synspective recently launched its first spacecraft, and another US firm, Predasar, plans to launch a 48-satellite network starting next year.

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

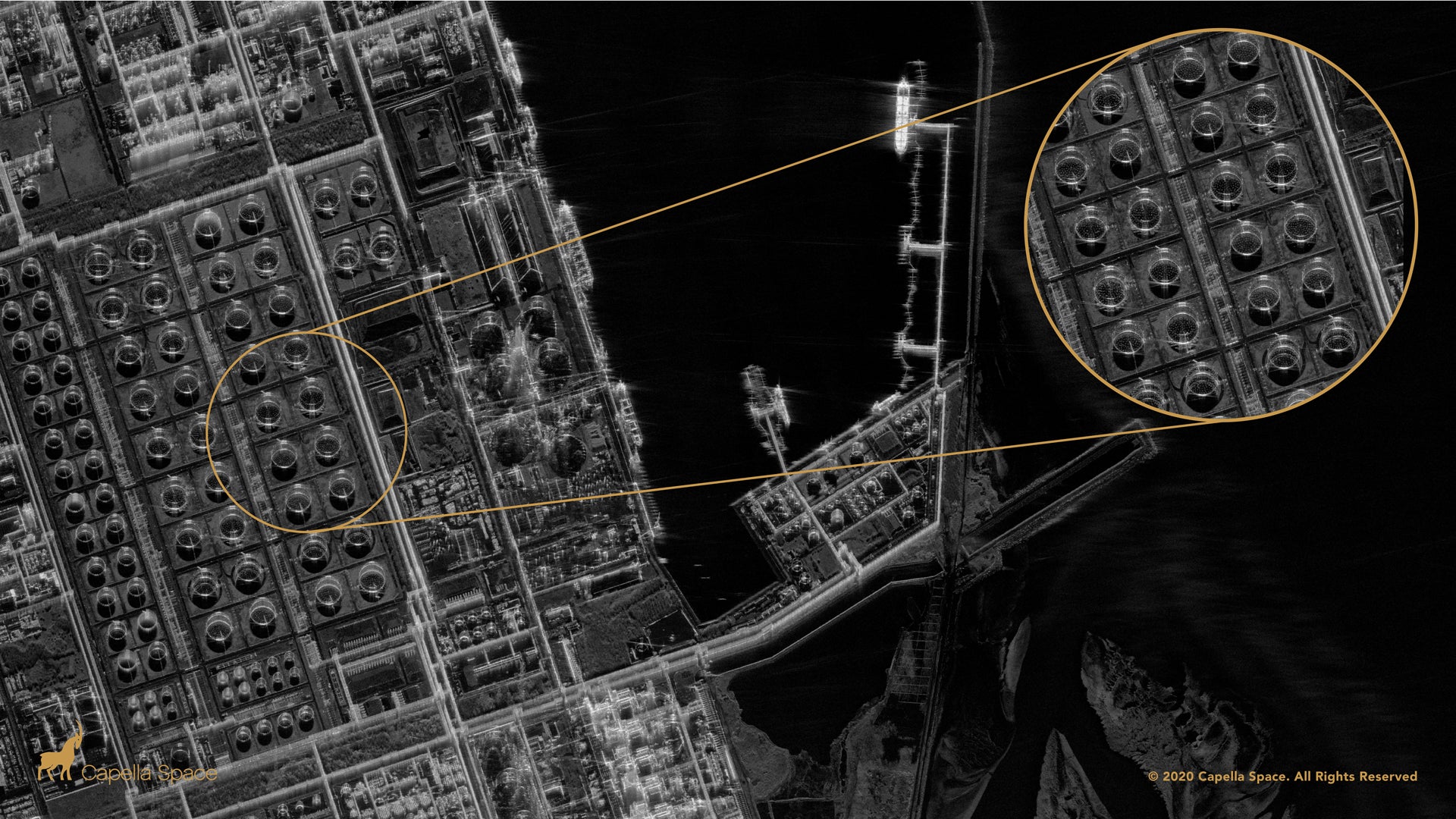

It’s Capella’s radar work, naturally. First up is this shot of the Jiuquan Launch Center in China:

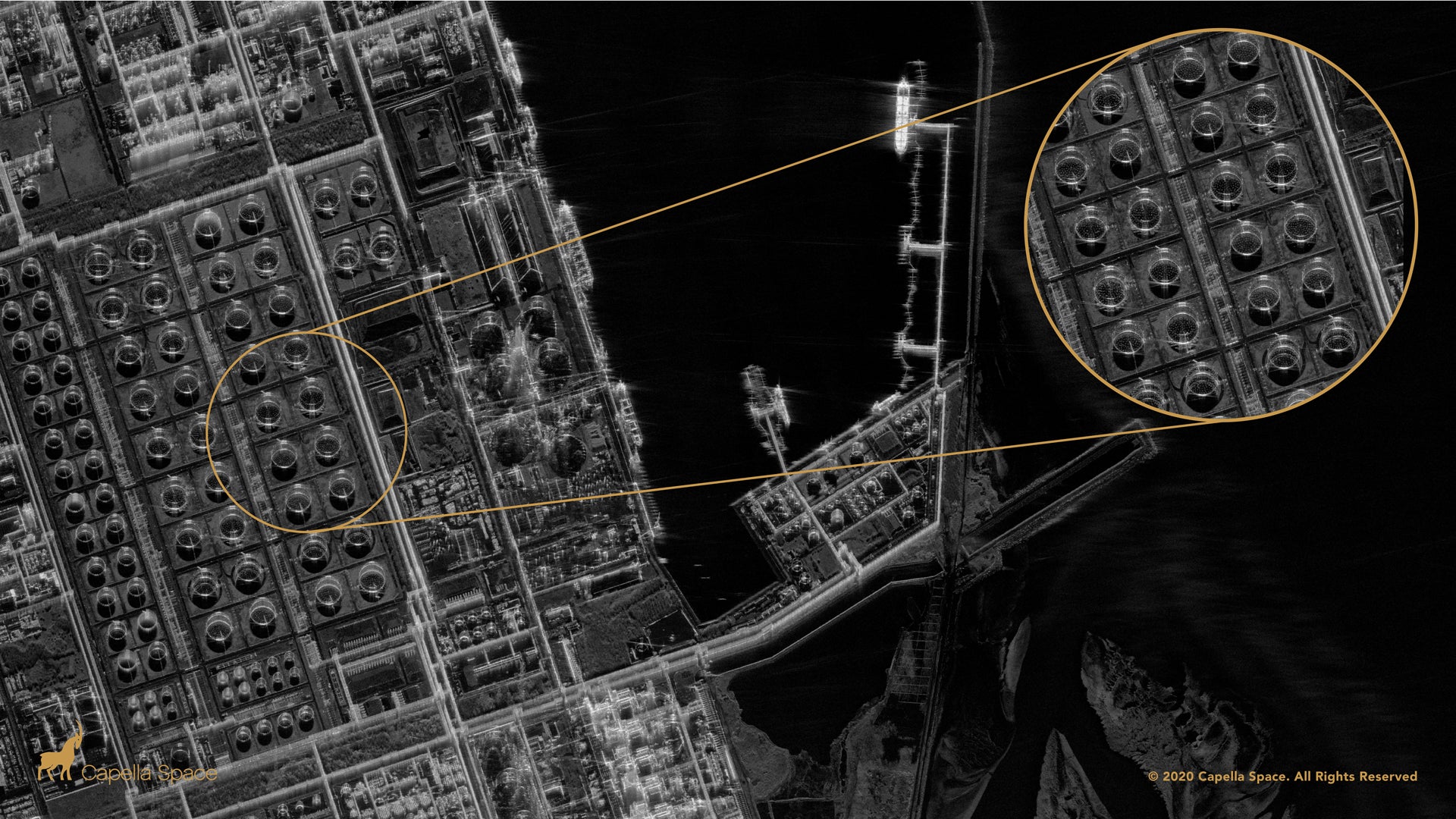

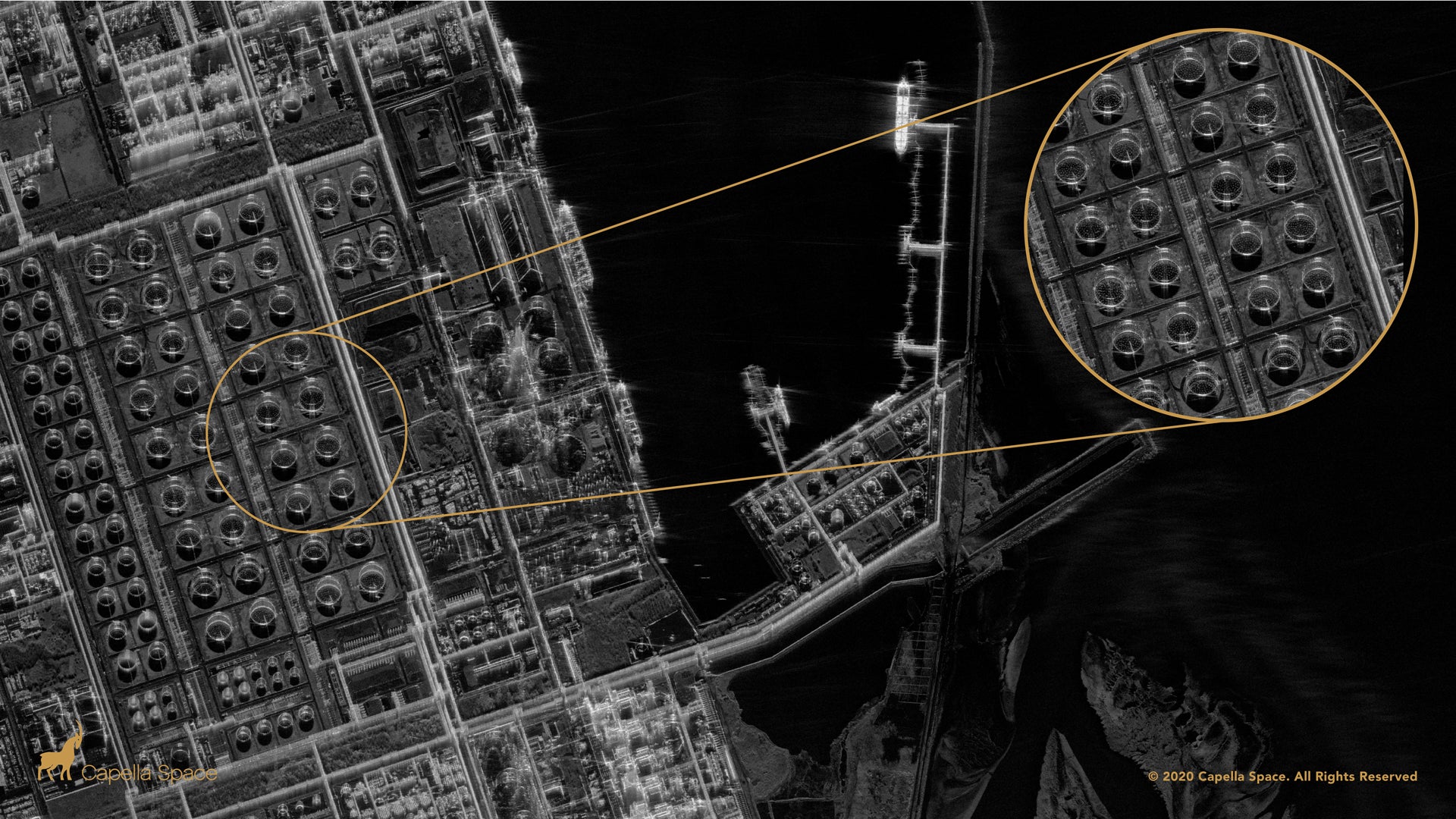

Here’s an image of an oil refinery in Taiwan, taken through cloud cover, which could be used by analysts to assess production and the amount of oil in storage:

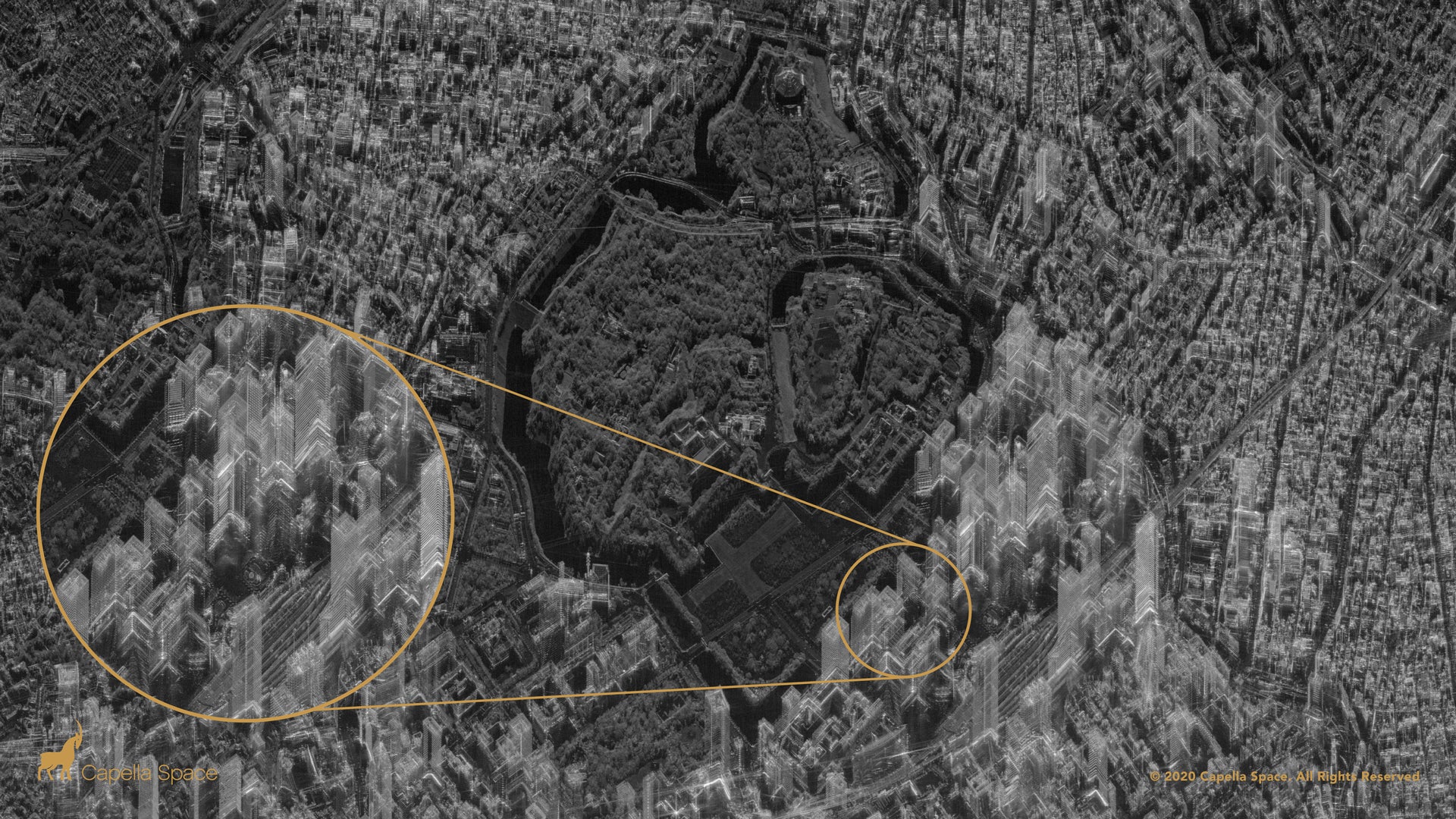

This shot shows the city of Tokyo:

👀 Read this 👀

Labor organizing has existed in the US for centuries. What’s different today is the “new” employee activism is happening in non-unionized workplaces, and in industries like tech and retail where employees have rarely leveraged their collective power. The goal is the same: Employees want a say in a company’s operations and ethics, in how employees are treated, and in how and where a company’s products are used. In the process, this activism is redefining the employer-employee social contract and modernizing the labor movement in a power struggle of epic proportions.

🛰🛰🛰

Return Policy. China successfully landed a spacecraft full of lunar surface samples in Mongolia on Dec.16 , completing the Chang’e 5 mission which launched in November. Assuming it returned with the samples safe and sound, it’s the first time humans have brought back anything from the Moon since 1976. The roughly 2 kg of moon rocks from the previously unexplored Oceanus Procellarum promise to give scientists new information about how the Moon formed and the history of our solar system. The complex autonomous maneuvers required to send a robot to the Moon, gather regolith, then launch into space and return to Earth also demonstrates the increasing sophistication of China’s space technology. As the globe gears up for a new season of Moon exploration, next up for China is sampling a different location in 2024, while the US plots to send its own fleet of private robots back to the Moon beginning as soon as next year.

What’s NASA’s NEO hold-up? According to the National Academy of Sciences, the key to spotting asteroids and other “Near Earth Objects” that might threaten humanity is using a space-based infrared telescope. It’s also one of the top jobs Americans want NASA to do. But, unexpectedly, the agency’s plan to do that has been delayed, apparently over budgetary concerns. This isn’t the first go-round on this project—the agency said it would not approve such a mission in July 2019, only to turn around and launch the current initiative just a few months later. Now, it’s on the back-burner again. If you have thoughts on what specifically is going on, do tell.

“The unexpected delay is disappointing, to say the least,” Casey Dreier, an expert at the Planetary Society, told Quartz. “The coronavirus pandemic has shown us the cost of ignoring low-probability, high-impact events. And an asteroid collision is the ultimate example of such an event. We must be prepared, and the first step in preparation is knowing the extent of the threat. As such, the NEO Surveillance Mission could be one of the most important spacecraft ever launched.”

Conjunction Junction. This week, NASA released a handbook of best practices for avoiding spacecraft collisions, part of the agency’s technical contribution to an ongoing conversation across the US government about how to manage ever-increasing activity in earth orbit. Joshua Krage, a NASA program manager working in the chief engineer’s office who led the effort to assemble this information told Quartz the agency sees promise in new technologies to monitor activity in orbit and automate satellite maintenance, but that “the biggest thing is sharing spacecraft ephemeris data, where the spacecraft is in orbit, with other operators as quickly and transparently as possible.”

Another space traffic problem. The increasing traffic into orbit is raising questions about its environmental impact, which wasn’t as relevant in the days of relatively constrained space activity. When abandoned rocket stages and retired satellites burn up in orbit, 60% to 90% of their mass can remain there as particulates, which researchers at the Aerospace Corporation say could impact Earth, possibly affecting the ozone layer. More work will be needed to quantify contaminants in the upper atmosphere and their effects on humanity.

How to think about a rocket test. From afar, it can be tough to tell when a rocket test is a failure or a success. After last week’s exciting Starship debut, I have to recommend Jeff Foust’s dive into the development of SpaceX’s next vehicle, and particularly his discussion of the difference between openness and transparency at Elon Musk’s company. This week also saw the small rocket firm Astra almost make it to orbit on the company’s fourth launch attempt in the last two years, and Eric Berger makes the case that this is a big deal.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 78 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send best practices for a space-themed holiday season, heuristics for rocket tests, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].