Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: An industrial base in space, how to land on Mars, and nuclear rocketships.

🚀 🚀 🚀

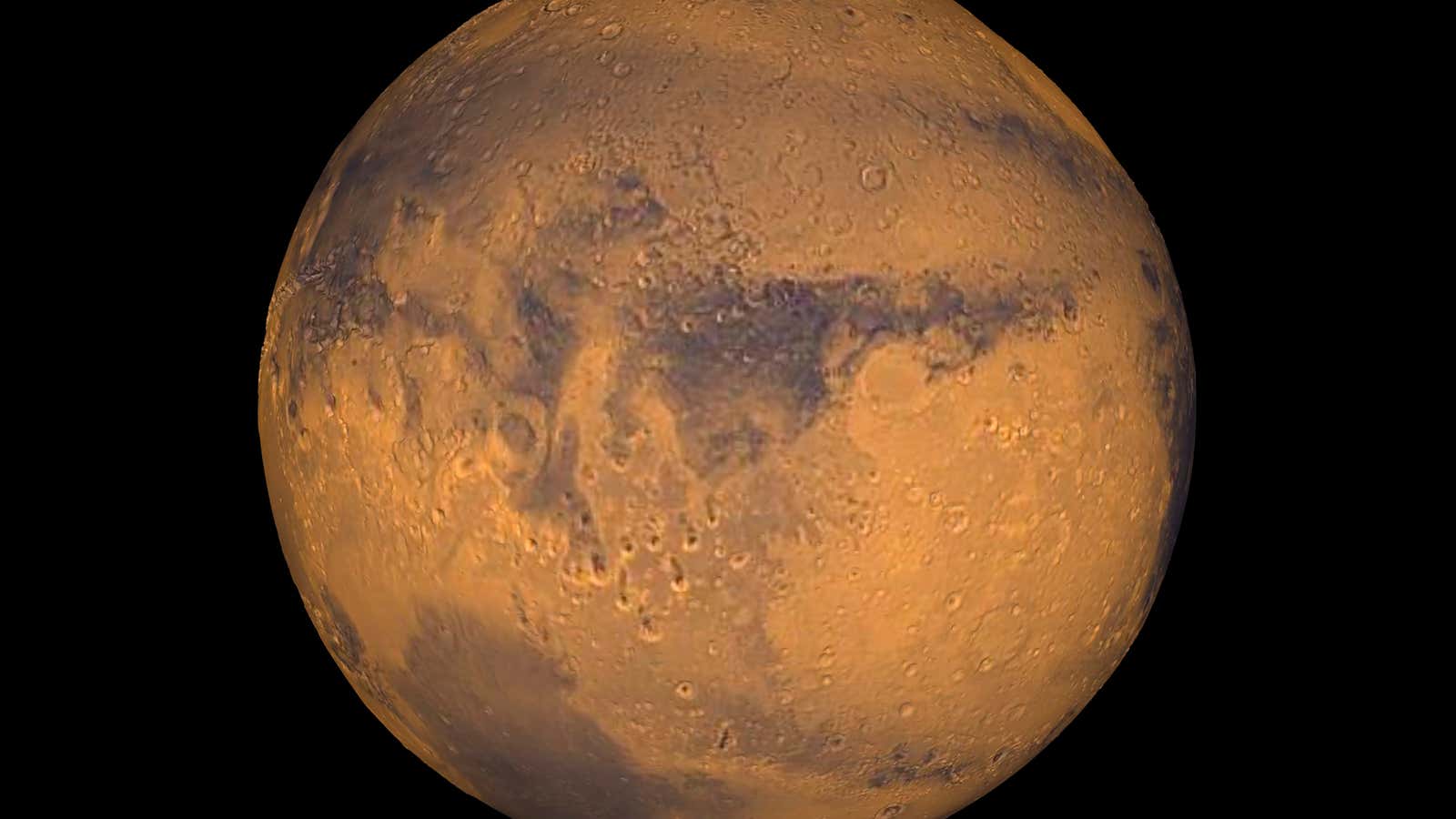

A robotic exploration mission sent by NASA will attempt to land on the Martian surface later today (tune in to watch starting at 2:15 US eastern time), catching up to two probes sent by China and the United Arab Emirates that arrived last week.

The US has been here before, and its rover is equipped, for the first time, with a small helicopter that will attempt to explore Mars in flight. China’s first trip to Mars will also attempt the difficult task of landing sometime in May or June. The UAE’s mission will orbit the planet, carefully mapping it with remote sensors.

The arrival of all three probes at the Red planet was driven by its relative proximity to earth last year when the missions launched, but also presents a symbolic lineup: The reigning space power and its main competitor, along with a third nation outlining a new model of national space investment.

“It’s really important that NASA and the US continue to lead in space exploration, continue to do these civilization-first type missions,” says Steve Jurczyk, a veteran NASA executive currently serving as the agency’s interim head until president Joe Biden nominates a permanent replacement.

But what does leading in space mean in a world where space technology is increasingly easy to access? The old model of the Apollo program, which signaled technological superiority to the rest of the world, is now outmoded.

“The US has been slow to catch on, to be frank, because it misunderstands some of the fundamentals of the new race,” says Peter Garretson, a retired US Air Force officer who is now a senior fellow focused on space strategy at the conservative-leaning American Foreign Policy Council. “For newly arrived space powers, repeating old tricks and doing new first-of-a-kind tricks still commands attention. But what really matters is who is establishing a long-term industrial and logistical base from which they can command long-term economic power.”

Garretson and Namrata Goswami, an independent space policy analyst, have written a book called Scramble for the Skies that outlines their expectation that space power will be built around exploiting the economic potential beyond earth. In particular, they fear China will outstrip other powers because of its long-term focus on development.

“Today, the context of space is much more about the economic returns,” Goswami told Quartz in an email. “A service like GPS or BeiDou offers the possibility of billions of dollars in return on investments. Countries like China are investing in space technologies like 3D printing, advanced robotics, and AI given their rationale of trillions of dollars of resources waiting on the Moon and asteroids to be harvested. The idea is not just showcasing space technology for its own sake, but towards a long-term strategic purpose.”

“US goals in space are not even one-thousandth as ambitious as what the Chinese have articulated,” Garretson says, citing Beijing’s detailed plans to outstrip the US as a space power by 2045—with a new space station, a moon colony, and the development of technology to capture solar power in orbit.

In comparison, American experience with space success during the Apollo program has led to a culture that favors symbolic moonshot projects over long-term, cumulative investment. But under recent presidents the growing role of public-private partnerships and policy directives prioritizing the economic development of space has bent policy toward this vision.

The Artemis program, launched under Trump to return US astronauts to the moon, provides a case study. The initial goal of laying the groundwork for sustainable long-term presence there fits with this new vision of space power, but the push to strip away the more complex parts of the program in order to meet an arbitrary 2024 deadline made less sense. Garretson says that delaying the 2024 date to build more useful lunar infrastructure makes sense. “Any part of the architecture that is expendable and is not able to be used by the private sector for their own purposes is a missed opportunity,” he adds.

As the US warily eyes China (and Russia) as rivals in space, it will also find itself working more with partners, both traditional and newly arrived.

“In some cases, the UAE has an advantage—they haven’t got a history, they don’t have these processes and procedure,” Jurczyk says, comparing the young space program with its private-sector start-ups. “In some ways they can be more innovative and lean forward in exploiting cube sats and small spacecraft. We’re supporting them with lessons learned engineering very complex systems and help them with enabling their innovation.”

For NASA’s rover Perseverance, a key part of its mission will be setting aside samples of Martian geology to return to earth. The return mission, launching in 2026, relies on a rover built by the European Space Agency to snatch the samples.

For the countries with new programs, space power isn’t just about achieving scientific milestones. It is about economic development, as in India, which began its space program just weeks after the Apollo 11 landing to enable weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and other development goals, Namrata says. And the message of exploration isn’t just for other countries but also for a domestic audience, allowing unelected governments in Abu Dhabi or Beijing to gain prestige in front of their people.

But small, wealthy countries like the UAE and Luxembourg, itself a satellite pioneer, see a chance to win more than just prestige. Garretson argues that these countries are well positioned to “be mediators and craft a new global consensus” on space activity, enabling access to other technologies and attracting financial activity, as well as bigger role in global affairs.

“Any nation that seeks to cary the banner of leadership in the world symbolically must also carry it in space,” he says.

🗣 🗣 🗣

Come join me next week on Tuesday, Feb. 23 for a virtual panel on space policy hosted by the American Enterprise Institute. We’ll be talking about why governments invest in space and the choices facing the Biden administration. I hope you’ll attend and bring your toughest questions!

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

Landing a rover on Mars is a difficult task because it has enough atmosphere to heat up a spacecraft that enters it, but not quite enough to rely on a parachute. Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab developed a system that combines friction, parachutes and ultimately a rocket-powered skycrane to deliver rovers to the Martian surface. Here’s a picture of the Perseverance rover undergoing tests to determine its center of gravity in preparation for that landing:

👀 Read this 👀

If your love life suffered during the pandemic, maybe you didn’t take it online. The online dating industry grew 13% in 2020, despite—or because of—restrictions in the way we socialize. My colleague Hanna Kozlowska dug deep into how this multi-billion dollar industry is adapting and expanding for this week’s Quartz field guide, which also examines how digital lovers have given up on geography and doubled down on niche communities.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Round up. CNBC’s Michael Sheetz reports that SpaceX has raised $850 million from private investors who value the vertically integrated space enterprise at a whopping $74 billion. (Still about one-tenth Tesla’s market value, but now more valuable that Northrop Grumman’s $50 billion market cap.) Analysts debate SpaceX’s burn rate, but the company has had little trouble raising funds to finance its ambitious goals and tech development programs, even as it maintains a healthy manifest of satellites to launch.

Round up II. Axiom Space, the human spaceflight company founded by former NASA official Michael Suffredini, said it raised $130 million this week. The cash tees up the company to move beyond its debut mission flying three wealthy passengers to the International Space Station alongside a former astronaut in a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, but the firm’s broader goal of developing a new orbital habitat will require financing at least an order of magnitude greater.

Atomic Rockets. The National Academy of Sciences has released a new report on the potential of nuclear-powered spacecraft, helpfully broken down by Axios’ Miriam Kramer. The efficiency and power of such technology isn’t really debated, but the challenge is developing and testing these engines without radioactive contamination.

More modern astronauts. The new space age is supposed to allow people who aren’t highly trained physical specimens to get into space, and the European Space Agency is taking that idea seriously with a pilot program to enable people with lower leg disabilities to become astronauts. The parastronaut program will recruit European citizens who will work to develop new technologies that allow them to live and work in space.

Spaceflight buys a rocket. The Japanese-owned, US-based launch broker said this week that it had purchased an entire PSLV rocket from India’s space agency in order to launch a Brazilian satellite, Amazonia-1. It’s the first time the company purchased an entire orbital launch vehicle for a single payload, and the first sale for India’s state-owned space commerce firm, NewSpace India Limited.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 84 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your theories of space geopolitics, schemes for nuclear-powered space propulsion, tips, and informed opinions to tim@qz.com.