A 30-year overnight space business success

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: The best space SPAC ever, a new president for Planet, and Myanmar’s coup strands a satellite.

🚀 🚀 🚀

More than a decade before today’s surge of space SPACs, one satellite company proved that a merger with a blank check company can indeed succeed.

That firm is Iridium, the satellite telecom valued at more than $5 billion. In 2020, its revenue grew to a record $583 million, and the company announced its first stock buyback plan. It’s been a lot of work to get there—and the circumstances might provide a word of warning to investors in today’s blank-check space acquisitions.

Iridium emerged from its turn-of-the-century bankruptcy as a private company, after the tech bubble popped and investors soured on satellite businesses. In early 2008, CEO Matt Desch knew the company needed between $1 billion and $2 billion of new capital to replace its satellite constellation, a project it would complete in 2019.

At the time, US capital markets were riding high, and a new round of SPACs had appeared following the initially successful acquisition of Jamba Juice by a blank-check firm in 2006.

One of those new SPACs was sponsored by Greenhill & Co., the boutique investment bank. Scott Bok, now Greenhill’s chairman and CEO, then served as the CEO of the blank-check company. Bank of America had pitched Greenhill’s executives on operating the buyout shell, arguing that their work advising on mergers and acquisitions made them a good fit for sponsoring one themselves.

The timing, however, could have been better. Bok’s SPAC closed its fundraising just a month before Bear Stearns’ collapse signaled the coming of the global financial crisis. Desch, meanwhile, was listening to offers from multiple blank-check companies, and picked a date to choose one of them. The day in question turned out to be when Lehman Brothers went under—and the markets crashed in earnest.

“I picked a bad day to down-select,” Desch jokes now, recalling investors telling him, essentially, “No offense, I like your business, but I can buy a bank for nothing, why would I buy a satellite company that still needs to spend $3 billion before it becomes cashflow positive?”

In the end, Iridium decided to go public with Greenhill’s SPAC.

“It was a little bit different from some of the more aggressive SPACs being done today,” Bok says—and not only because today’s blank-check companies can see their prices rise 50% or more above the pro forma $10 share price when they announce their acquisition targets. (Back in 2008, if a SPAC’s price increased to $10.10, “you thought you did good,” Bok says.)

Iridium, he notes, “had real cash flow, it had real revenue, it was an operating business. Where it was somewhat like the more speculative ones today was that it did have a huge need for capital and some degree of technological risk to put a new fleet of satellites in the sky.”

Indeed, some space businesses going public today have yet to even bring their products to the market.

Iridium earned $260 million in 2007, before going public the next year with a valuation of $591 million. Virgin Galactic’s recent SPAC merger relied, like other contemporary blank-check acquisitions, on projections of future revenue. It went public in 2019 with a valuation of $1.5 billion, against forecast 2020 revenue of $31 million. It’s actual revenue in 2020: $238,000.

“By the time we went public, we had robust financing,” Desch says. “The risk that we had ahead of us, which frankly a lot of people said was a lot of risk, pales in comparison to the risk some of these current SPACs have.”

Armed with capital from the public markets and financing from France’s export-import bank, Iridium went about the business of developing, building, and launching its next-generation spacecraft, 66 of which today provide telecom services to customers as diverse as the US military, cruise ships, and, through hosted payloads, airlines.

It was not all roses along the way; Iridium’s NASDAQ shares generally traded below $10 for the next seven years. But in 2017 it became clear that Iridium would complete its new constellation on the back of SpaceX’s reusable rockets. As space-based businesses of all kinds became more palatable investors, the stock surged toward its present price of roughly $40 a share.

“We’re a 30-year overnight success story,” Desch says pointedly, a reference to the origins of Iridium as a Motorola project in the early 1990s. Much has changed in space technology and the capital markets since then, but space SPACs may still take longer to pay off than many investors envision.

“Everything that we as investors believed about Iridium at the time turned out to be true,” Greenhill’s Bok says. “The thing we may have underestimated was that it took quite a while for the market to really buy into that. I suspect a lot of the more speculative SPACs being done may well suffer the same process.”

🌘 🌘 🌘

IMAGERY INTERLUDE

Batteries overboard! This image shows a pallet of nickel-hydrogen batteries being tossed from the International Space Station over Chile after astronauts replaced them with newer lithium-ion batteries.

The pallet will orbit Earth for two to four years before gravity tugs it low enough to re-enter the atmosphere and burn up. Because the pallet was jettisoned below the relatively low-flying ISS, it shouldn’t pose a threat to other spacecraft, but its presence is a reminder of the problem of lingering debris in orbit.

👀 Read this 👀

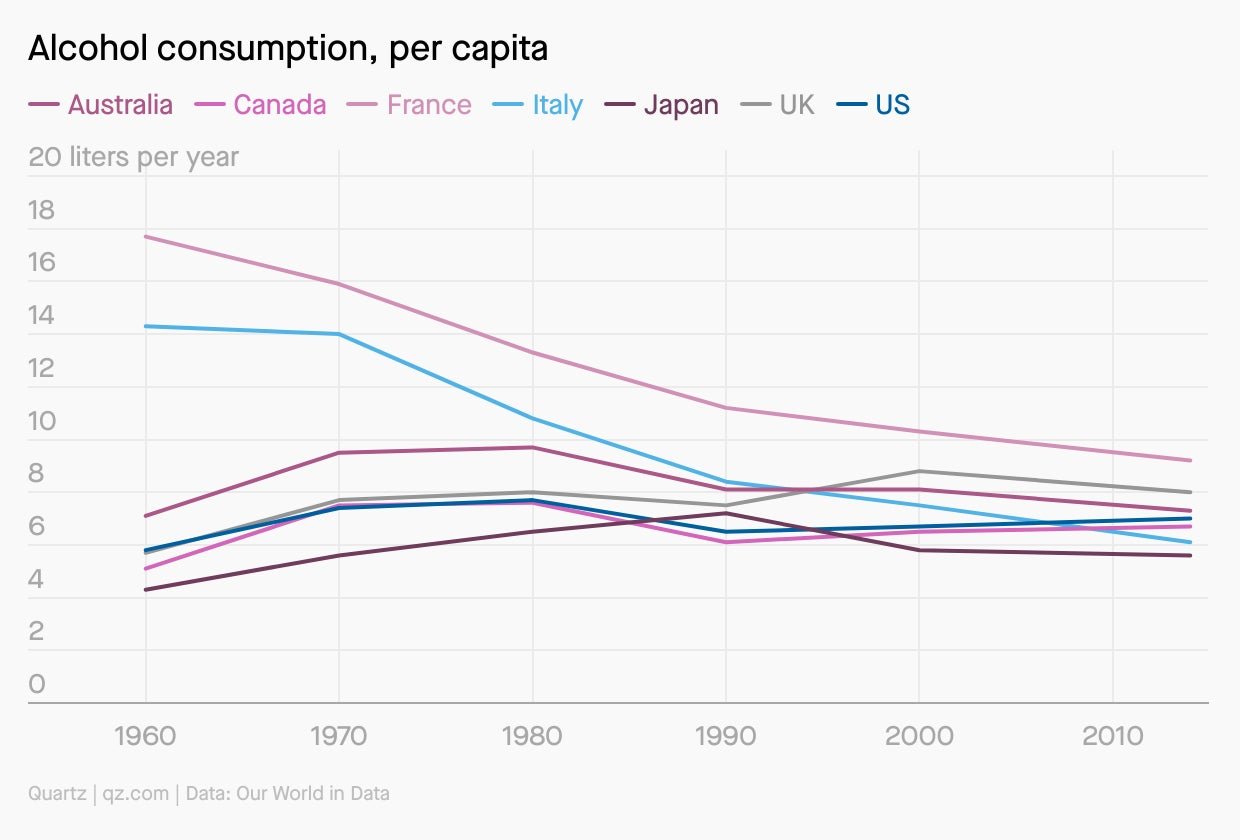

Many people around the world are drinking less booze; in some places, dramatically less:

Quartz’s latest field guide examines a new spin on the temperance movement that frames sobriety for a 21st century audience—as a lifestyle choice.

🛰🛰🛰

SPACE DEBRIS

Planet’s presidential inauguration. Earth-imaging company Planet has hired its first president of product and business. That’s Kevin Weil, lately the co-creator of Facebook’s cryptocurrency experiment Novi, and previously the top product exec at Instagram and Twitter.

Weil will be charged with continuing the data-focused strategy unveiled by the company in 2019. While building the infrastructure to collect daily data about the planet was its first challenge, the current goal is to find ways to make those insights immediately valuable to organizations with no interest in space at all.

“It’s a delight that our business increasingly looks like that of a software company, with product features driven by software advances that deliver value on top of our satellite data,” Planet CEO Will Marshal wrote in Weil’s hiring announcement, which also noted that like Marshall, Weil cares about global sustainability efforts—he’s on the board of the Nature Conservancy.

Myanmar’s coup, in space. The ugly situation in Myanmar, where the military has overthrown the democratically elected government, has had repercussions in space: A small imaging satellite Myanmar built in collaboration with a Japanese university is being held on the International Space Station for fear it could be used by the junta, which is already implicated in human rights abuses.

National Relativity. The US Department of Defense has signed a contract with Relativity Space, the 3D-printing focused rocket-maker, to fly small satellites into orbit in 2023. It’s a sign of confidence in Relativity’s program, but with Virgin Orbit now operational, Astra and Firefly saying they’ll be launching this year, and the pressure of existing competitors like SpaceX and Rocket Lab, competition in the small-launch business is only rising.

Commercial spaceflight with Chinese characteristics. China’s latest five-year economic plan includes significant support for the country’s burgeoning commercial space industry, including the construction of a dedicated spaceport.

Commercial spaceflight with American characteristics? Three major trade groups—the Aerospace Industries Association, the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, and the Satellite Industry Association—sent a letter to US Commerce Department secretary Gina Raimondo urging to staff up the depatment’s Office of Space Commerce. There is concern in the space industry that it may get a short-shrift in the Biden administration—but that’s likely premature.

How do you build such an expensive rocket? Ars Technica’s Eric Berger reports that US president Joe Biden’s NASA transition team has begun a review of the expense of Boeing’s Space Launch System, a very large rocket intended to carry humans to the moon and beyond. It’s been significantly delayed and over budget throughout. The project has vociferous political support, but this news has echoes of the budgetary concerns that drove the cancelation of a similar rocket plan at the beginning of the Obama administration.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 88 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send more SPAC gossip, space debris solutions, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].