Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere, this time hosted by guest writer Casey Dreier, space policy analyst at the Planetary Society. Please forward widely, and let us know what you think. This week: lunar contracts and Webb delays.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The next American to set foot on the Moon will travel in a NASA spacecraft, launched from Earth atop a NASA rocket. But the space agency will buy practically everything else for the mission from commercial suppliers.

NASA is in the midst of a great experiment: Can commercial partnerships—like the ones that now provide cargo and astronauts to the International Space Station—deliver the same cost savings in deep space?

Compared to so-called cost-plus contracts, in which the government is on the hook for any cost overruns or program delays, commercial partnerships are fixed price. Cost overruns are borne by the contractors. This approach saved NASA billions of dollars in low-Earth orbit when the agency needed to replace capability lost by the retirement of the space shuttle. It also enabled the rise of SpaceX, the world’s most successful private space company.

Heady with that success, NASA is extending its commercial ambitions toward the Moon. Spacesuits, a new lunar space station, payload delivery systems, and even the human lunar landing system itself are being developed with fixed-priced commercial contracts. Dozens of companies are vying to provide these services.

Notably, we have yet to see success in commercial partnerships beyond Earth orbit (science missions to the Moon won’t begin until 2022 at the earliest). But that hasn’t stopped calls to extend this model even further. A recent study released by Caltech’s Keck Institute for Space Studies calls for a commercial partnerships approach at Mars with a special focus on delivering payloads to the surface—currently the exclusive domain of the US and Chinese governments.

I should make it clear that I support this approach and am excited about it. Nothing like this has happened before, and it is important to grow the space business beyond the small set of stalwart government contractors. But we should also understand the outcome is not a given. There is no guarantee this method will work beyond the relatively forgiving environment of low-Earth orbit, which benefits from ease of communication, low launch costs, and an extant commercial market. The Moon offers none of those benefits, to say nothing of Mars.

There is no historical comparison to draw from here. This is an experiment. And experiments can fail.

We’ve already seen failures. Planetary Resources, the asteroid mining company, dissolved in 2018. Bigelow Aerospace, purveyor of inflatable space habitats, laid off its entire workforce in 2020 and turned over ownership of its space station module to NASA. The private lunar lander Beresheet crashed during its landing attempt in 2019. And according to Elon Musk, even SpaceX faces a real threat of bankruptcy due to a troubled engine development program.

The motivation for cost-plus contracting was to ensure that government requirements wouldn’t drive a contractor into bankruptcy when tasked with developing a novel project. No one had ever built a Moon lander before Apollo, for example, and no one knew how much it would cost. For national priorities like Apollo or the International Space Station, the goal was to develop the final product, regardless of the cost. In that sense, the government risked dollars for a guaranteed capability.

The commercial services model flips that risk posture. The government no longer risks cost, but instead faces a possibility that its commercial partner may run out of money, fail to provide the promised service, or otherwise collapse. It no longer pays to guarantee a final product. In mature markets, this risk is mitigated by having a number of providers to select from should one or two fail. But deep space is not yet a mature marketplace. There is no market and no significant customers other than government space agencies. This can all change, and NASA and its commercial partners are betting that it will. But again, it’s a risk.

We are at a point in the history of space exploration where experimentation like this is necessary. We know the outcome of the old way of doing business. Cost-plus programs like NASA’s Space Launch System rocket and Orion crew vehicle are many years delayed and billions of dollars over budget. Successfully developing commercial services at the Moon would free up billions of dollars for NASA to invest in cutting edge programs beyond the realm of commercial activities, like in-space nuclear power, science-driven exploration of the planets and cosmos, or the search for life beyond Earth.

NASA has placed its future of humans on the lunar surface on a single commercial partnership, with SpaceX—a mighty risk considering it represents the future of US human spaceflight. The next decade of lunar science now depends on a handful of unproven commercial providers. But that’s OK. Let’s embrace the risk, and be ready to support NASA and other agencies that dare to experiment with new ways of extending humanity into the cosmos.

Regards,

Casey

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

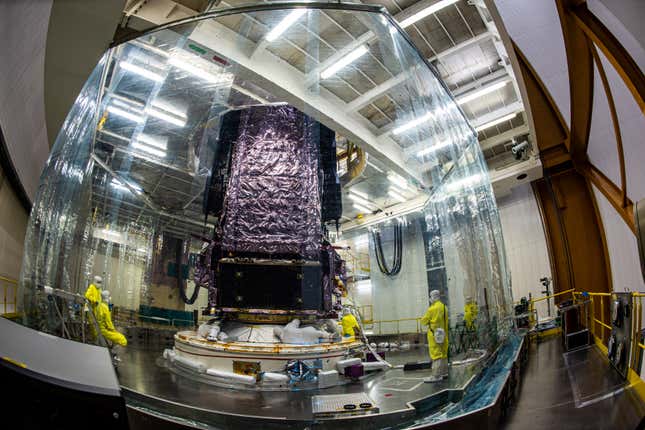

The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, already 14 years late, has been delayed for another couple of days as technicians work to fix a communication glitch. NASA said the telescope is now scheduled to depart on its 1 million-mile journey to study the history of the universe on Dec. 24.

Here it is as it was installed atop its ride, an Ariane 5 rocket. It was a delicate operation that involved a giant “shower curtain” to avoid contamination.

Unlike the Hubble telescope, which has undergone repairs in space, the $8.8 billion JWST is on its own after lift-off.

🌍🌎🌏

Start your day right—and that includes your first bleary-eyed scroll through the inbox. Improve your awakening by signing up for Quartz’s Daily Brief, an efficient and enlightened guide to the news of the day.

🛰🛰🛰

Space Business will take a break for the holidays. See you next year! Writer Tim Fernholz is on leave. He’ll be back in 2022.

This was issue 118 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send oversized shower curtains, tips, and informed opinions to ana@qz.com.