The entrepreneur behind mega constellations wants to make them safe

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Greg Wyler’s new company, Starship update, and the SPAC reckoning.

🚀 🚀 🚀

The godfather of massive satellite constellations is back with a new business—and a warning.

Greg Wyler, a serial entrepreneur whose companies O3B and OneWeb helped tee up the rush of investment into satellites in Earth orbit, announced this week that he had raised $50 million for a new project, E-Space. Without revealing many details, Wyler described a company that exists in response to a trend he helped kickstart: The startling growth of activity in orbit.

When Wyler started the satellite telecom O3B in 2007, named for the “other three billion” unconnected customers he hoped to plug into the global conversation, there were fewer than 1,000 active satellites in Earth orbit. Today, there are more than 4,500.

Wyler sold O3B to the European satellite giant SES, and in 2014 moved on to pitching an even more ambitious satellite network, featuring thousands of low-flying spacecraft, first to Google and then SpaceX. Differences of opinions with both companies led Wyler to form his own firm, OneWeb. Elon Musk, still enamored by the idea of a massive satellite network, began developing SpaceX’s Starlink network.

Starlink raced ahead, thanks to SpaceX’s fleet of rockets, and now operates nearly 2000 satellites. Wyler left his management role at OneWeb in 2017, but after emerging from bankruptcy in 2020, the company now operates more than 400 satellites. Dozens of other companies and countries are plotting similarly large networks of spacecraft, notably Amazon, Canada’s Telesat, and the governments of the US and China.

The massive new investment in space, driven by the falling cost of getting there on modern rockets, has opened a world of new potential benefits. It’s also created significant concern about potential collisions between spacecraft, and the debris such crashes create. These worries have been exacerbated by more frequent anti-satellite weapons tests as the growing importance of space leads countries including China, Russia, and India to demonstrate their ability to strike in orbit.

With E-Space, Wyler is no longer selling dreams of connectivity. Instead, he talks about resiliency and sustainability, creating satellites to withstand a potential chain reaction of collisions in orbit known as a Kessler event, something he says is “darn close to inevitable.”

“There are no satellites today that will survive a Kessler event,” he says. “There was a day when people thought that the fluids from jet engines would never harm the sky and the Earth because it’s so big…[My background] puts me in position to really understand where all this is going.”

Wyler says the company’s still confidential satellite architecture is cheap enough to launch tens of thousands of redundant spacecraft, but each presents a small profile as it moves through orbit, reducing the chance of collisions. Anton Brevde, a partner at the fund Prime Movers Lab, the only outside investor in E-Space, says the satellite design is the company’s key advantage. The spacecraft is also designed to absorb impact, rather than break into hundreds or thousands of pieces, and in a future iteration, collect debris it encounters. Space engineers Quartz spoke to were skeptical about these ideas but unable to comment without more detail.

Tim Farrar, a satellite industry consultant, speculated the specific radio frequencies E-Space plans to use might lend themselves to a network that also uses radio spectrum reserved for terrestrial purposes. That jibes with job postings on E-Space’s website seeking engineers familiar with 5G, the mobile communications protocol.

Wyler says he hopes to offer bespoke constellations to corporate and government customers. Such an architecture might be best applied to Internet of Things applications, with utility companies monitoring their infrastructure or cities tracking activity in the streets.

Satellite communications for IOT remains a nascent field, with space connectivity generally too expensive for mass deployment. One company promising to change that is Swarm, which was acquired by SpaceX last year and abruptly went silent. Given Elon Musk’s past interest in Wyler’s work, we’ll hear a lot more about SpaceX’s IOT plans if E-Space gains commercial traction.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Thanks for reading while I was away! I hope you enjoyed our guest authors, who kindly stepped in so I could enjoy the first few months of life with my son Oscar. I’m very grateful to my Quartz colleagues Clarisa Diaz, Adario Strange, Nicolás Rivero and Ana Campoy, and to outside contributors Sarah Scoles, David W. Brown, and Casey Dreier.

📉 📉 📉

Imagery interlude

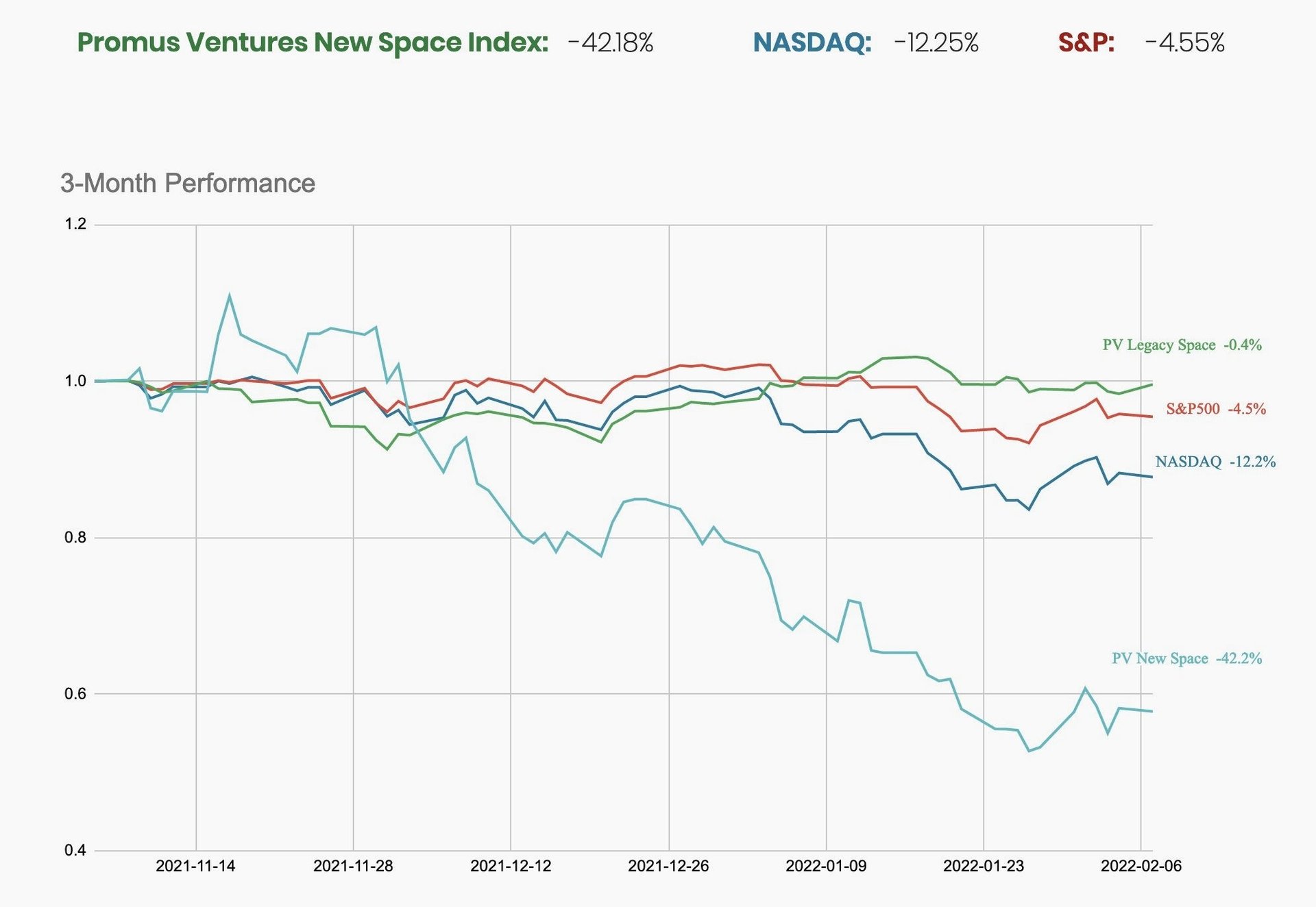

Here’s a telling chart shared by Promus Ventures at the Small Satellite Symposium. It shows an index they’ve created of publicly traded new space companies, many of which went public through blank-check acquisitions, and how it has performed against legacy space companies and markets overall.

It’s not great news for private space fans, but the passel of firms that went public in recent years was a mixed bag, featuring promising enterprises and others desperate for funding. On the bright side, space entrepreneurs are bullish about private fundraising—and the possibility of snapping up undervalued public companies on the cheap.

🔊🔊🔊

Innovation isn’t always welcome. When the first baby was born from a frozen egg in 1996, the technology was so new that the mother refused to reveal her name. Now that egg freezing is approaching the mainstream, the question is how well it works, and who’s missing out on access. Learn more about the future of freezing eggs in this week’s episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

🛰🛰🛰

Space debris

When will Starship fly? This evening, Elon Musk will give his annual update on the state of his company’s next-generation rocket, known as Starship. Eric Berger has broken down the big questions we hope Musk will answer.

Why are as many as 40 brand-new Starlink satellites burning up in the atmosphere? They were launched just as a small solar storm hit the Earth, which created enough drag to pull them down into the atmosphere before they could turn on their thrusters to reach a higher orbit.

How much will commercial space stations save NASA? As much as $1.8 billion annually after the ISS is retired, but there are plenty of caveats.

When will Astra deploy a satellite? Astra, the publicly traded rocket start-up, scrubbed a planned launch of four NASA satellites after a telemetry problem was discovered. It’s not clear when the company will attempt to deliver its first spacecraft.

How is that Tesla that Elon Musk launched into space? After a nearly 2 billion mile journey, it’s…probably fine.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 122 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your Starship predictions, Olympic-themed space art, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].