Better hardware, less TV: A snapshot of the space economy in transition

Dear readers,

Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: Measuring the US space economy, an R&D mystery, and the war in Ukraine.

🚀 🚀 🚀

A few weeks ago, Elon Musk responded to critics who complain about money governments and entrepreneurs invest in his beloved space activities.

“Is he suggesting that we just spend everything on space? No, maybe half a percent [of federal spending], something like that,” he mused at an event for his latest rocket.

NASA’s budget is currently about 0.5% of federal spending, but thanks to the hard work of economists at the Bureau of Economic Analysis, we also know that’s about how much was spent on space in 2019—$194.6 billion, or .5% of total gross output in the US that year, which created 354,000 jobs.

“We only spend half a percent of the economy on space and look what we have from it,” Tina Highfill, a BEA economist, says.

Highfill began tracking the space economy in 2019, working through government statistics to isolate spending on everything from satellites to astronomy classes. The first estimates, for 2012 through 2018, were released last year, and earlier this year the project added 2019 and, as importantly, adjusted the statistics for inflation.

The effort is important because most measures of space-related economic activity rely on revenues or investment, and thus suffer from double-counting, or can’t easily strip out space business from a company’s other work.

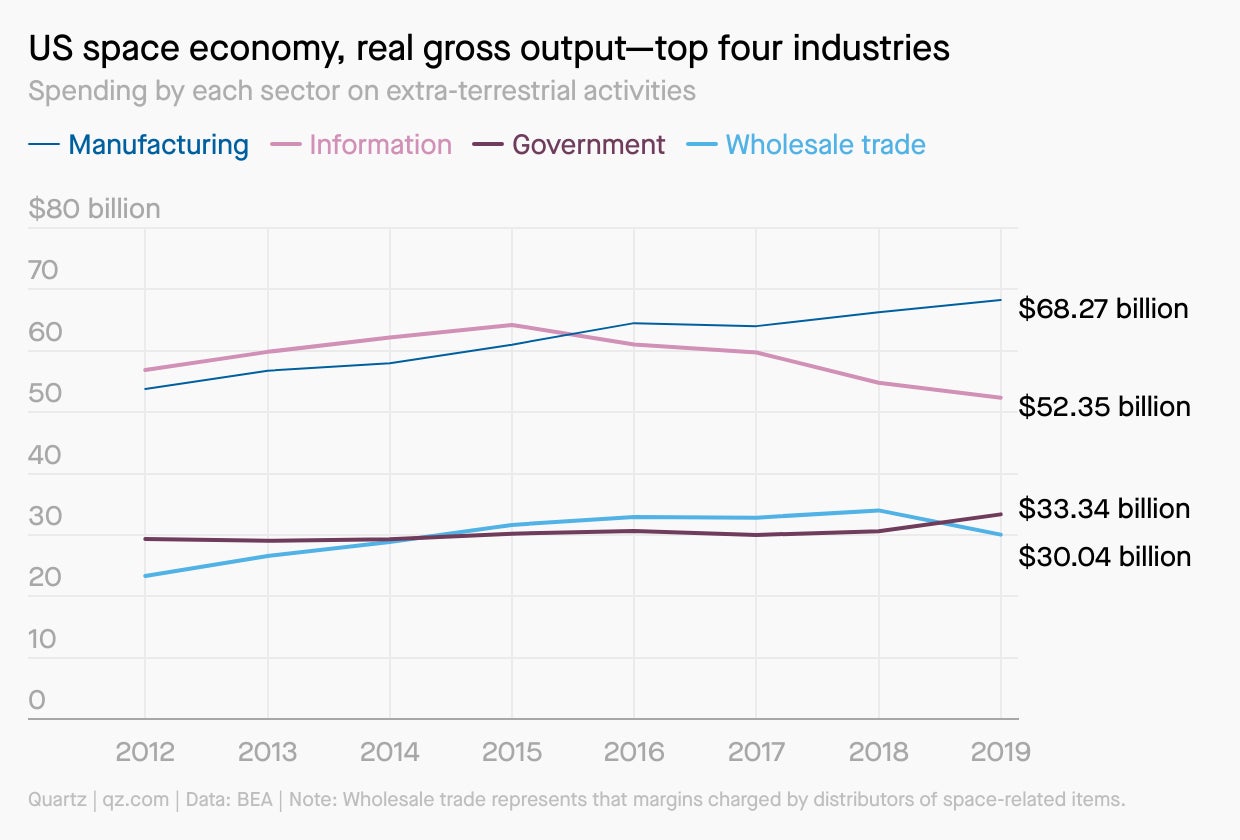

The statistics show a space economy in transition: Manufacturing of advanced technologies like rockets and satellites grew faster than the US economy, but spending on information services hasn’t yet seen a boost from all this new infrastructure.

Highfill was able to solve a mystery in last year’s numbers: During an apparent boom in businesses building rockets and satellites, nominal spending on space-related manufacturing fell between 2012 and 2019. But after adjusting for inflation and the changing quality of the products, the statistics tell a story of innovation.

“Production was actually increasing but prices were declining,” she says, noting that for “a million-dollar satellite in 2012 versus a million-dollar satellite in 2019, the 2019 satellite is going to do a lot more.”

Meanwhile, one of the largest space businesses, satellite TV, has seen spending fall as cord-cutting with terrestrial internet becomes a cheaper option. I’ll be watching to see if major efforts to deliver internet from space, like Starlink, OneWeb, and Kuiper, push the trend in this category around.

The rest of the growth in the sector is driven by increasing government spending, not just at NASA but also by organizations like the US Space Force.

Next year’s budget for further work on this data isn’t set, but Highfill hopes to continue adding new years to the dataset and extend it further backward in time. She’d also like to translate these statistics on spending into measures of activity—how much money is spent on, say, space tourism or launch vehicles or Earth-observing satellites—which could make them more accessible.

While the US space economy isn’t close to the trillion-dollar space goldmine heralded by space visionaries, it’s impact is significant and growing. Between 2012 and 2019, financial service businesses increased their spending on space goods eight-fold. Other sectors like construction, retail sales, and manufacturing of all kinds grew at double-digit rates.

“Double-digit growth in gross output and value added is very unusual,” Highfill concludes.

❓❓❓

Help solve a space data mystery.

Between 2014 and 2015, private sector research and development spending as measured by the National Science Foundation in the “radio, television, and wireless communication equipment manufacturing” category fell by $3 billion.

That category is mostly driven by satellite research, per the NSF, but it’s not clear what led to the plunge, which continued until 2019, the end of the data set. After consulting with experts, Highfill speculates it might be related to the rise of small satellites, which were proven out in that time period and thus required less R&D spending afterward.

Still, $3 billion is a big change in spending on what are supposed to be cheap satellites. If any readers have a plausible theory, please reach out.

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery interlude

Despite the conflict in Ukraine and some outrageous rhetoric, the US and Russia continue to collaborate to safely operate the International Space Station. Days before the conflict began, an uncrewed US supply spacecraft called Cygnus, a newer version of the vehicle pictured below, arrived at the ISS.

The design of the station requires technical contributions from both sides to keep it in orbit, with US modules generating solar power and Russia using its Soyuz spacecraft to boost the altitude of the station when it sinks too low. The new Cygnus can use its rocket engines to lift the ISS—which may make some Russian capabilities redundant.

🔊🔊🔊

The staying power of space-age food. Science-fiction is a great way to look at the past’s idea of what the future might look like, and fish sticks—those humble frozen rectangles that first emerged in the 1950s—are arguably the past’s idea of the future of food. But novelty isn’t the only reason fish sticks are still around; they could also help solve food challenges in the present. Learn more with this week’s episode of the Quartz Obsession podcast.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

🛰🛰🛰

Space debris

Russia hits back at OneWeb after Ukraine sanctions. The Russian space agency is refusing to launch satellites for OneWeb until the UK government sells its stake in the private space internet project and promises it won’t be used for military purposes. OneWeb is defying these demands, but will suffer while its expensive satellites are trapped. Russia, meanwhile, will face a long-term loss of international confidence in its lucrative satellite-launching services on top of everything else.

What the invasion looked like from space. It’s a story we tell with each new conflict, but the rapidly advancing capabilities of private satellites and open-source analysts have put a spotlight on images of war that were once restricted to secure rooms at three-letter agencies.

A complicated effort to boost Ukraine’s space intel. Max Polyakov, the wealthy Ukrainian recently forced by the US government to divest from rocket-maker Firefly Aerospace, is urging satellite operators to share data with his firm EOSDA, which he says will act as a clearinghouse for the Ukrainian military. However, the same regulatory issues that forced him out of Firefly are also complicating these efforts.

The cost of a Moon mission: $4.1 billion. NASA inspector General Paul Martin minced no words at a hearing this week when he pointed out the cost-per-flight of mooted Artemis Moon missions is now estimated at $4.1 billion a pop. He called it “a price tag that strikes us as unsustainable,” which, yeah, jeez.

Musk sends Starlink to Ukraine. After hearing requests on Twitter, the SpaceX founder sent terminals for his space internet network to Ukraine, which is using all avenues to continue telling its story to the world.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 125 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your speculation about the satellite R&D mystery, the best uses of open-source space intelligence in Ukraine, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].