The Race to Zero Emissions: The oil company of the future is an energy company, or nothing at all

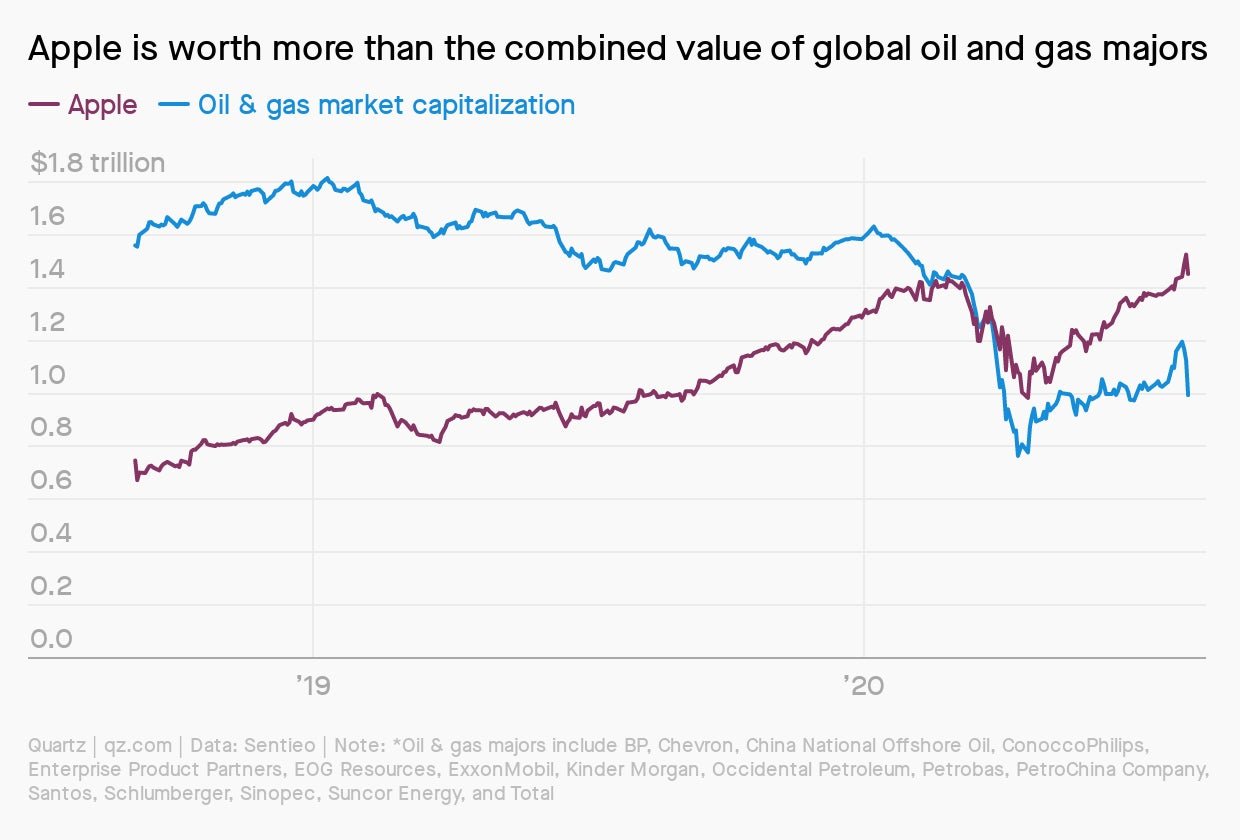

For this bonus edition of Race to Zero, we thought we’d start with a question: What company is worth more than the major private oil and gas companies combined?

For this bonus edition of Race to Zero, we thought we’d start with a question: What company is worth more than the major private oil and gas companies combined?

Is it:

- Nike

- Wells Fargo

- Apple

- Chipotle

Since the coronavirus struck, oil and gas companies have seen their fortunes (and share prices) plummet. Oil majors like ExxonMobil are staring at a scary future: carbon constraints, electric vehicles, falling prices, oversupply, and forced phase-outs all cloud their future.

Oil and gas companies now face the possibility of a managed decline, extracting as much money as possible out of existing oil fields and infrastructure, while restricting new investments. For many firms, particularly in Europe, the coronavirus pandemic is a signal that peak oil demand may be closer than they thought—or even in the rearview mirror.

The alternative? Turning into energy companies. I explored that future this week, in Quartz’s field guide to the dramatic fossil fuel bust kicked off by Covid-19.

A few firms have already made the leap. One is Ørsted, formerly the Danish Oil and Natural Gas company. After selling off its oil and gas assets in 2017, Ørsted is on track to eliminate fossil fuels entirely by 2025. Coal and gas make up just 13% of its power mix, and the company commands about a quarter of the world’s fast-growing offshore wind market.

That was a lucrative bet. The company has roughly tripled in value since its 2016 IPO, far outperforming every major oil company. Ørsted says sustainable energy systems were “the key to our growth over the past decade.”

It might not be too late for supermajors to catch up. The renewable energy market has decades of growth ahead. Supermajors could turn their fossil fuel assets into cash machines, reinventing themselves as electric utilities that extract energy from the wind and sun and deliver it to your car battery and LED light bulbs.

Oil companies have started talking the talk, discussing the coming energy transition in boardroom meetings. Yet their balance sheets tell a different story. Investments in renewables and low carbon technologies by private oil and gas companies still account for less than 10% of their capital expenditures.

But even if the investments were there, a successful transition seems unlikely, says energy economist Philip Verleger. “Very few companies have transformed from being really good at one business to really good at another,” he said. “It’s hard to see how Shell will be really good at electricity.”

Investors now face the question: If you want to invest in an all-electric future, why do it through a struggling oil company? Plenty of successful clean energy companies already exist. They’d love to take investors’ money.

To read more about Ørsted and the tough road ahead for oil companies trying to transition to energy, you can become a Quartz member ✦ and read the full guide, which also covers the fossil fuel industry’s 150-year-old boom/bust cycle, its struggle to recruit new talent, and the collapse’s impact on growing economies in Africa. Try it out for seven days free, or go all-in with a yearly subscription, half off with the code SUMMERSALE.

Stats to remember

As of June 23, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 416.13 ppm. A year ago, the level was 413.33 ppm.

Have a great week ahead. Please send feedback and tips to [email protected].