Students at India’s private English-medium schools can barely read English

India’s urban private schools, catering to middle-class families, were for long seen as better off than most institutions in the country’s outdated education system.

India’s urban private schools, catering to middle-class families, were for long seen as better off than most institutions in the country’s outdated education system.

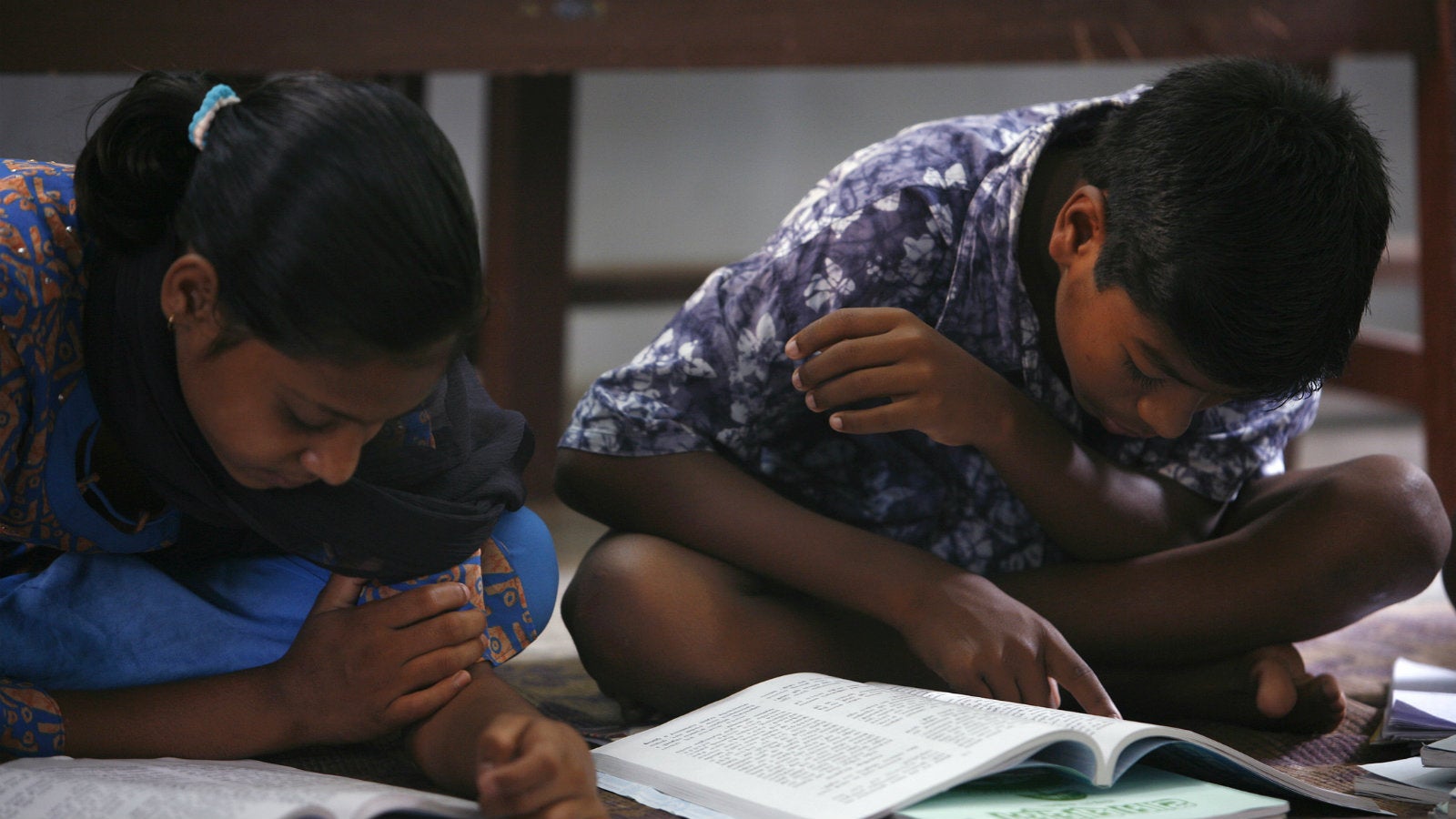

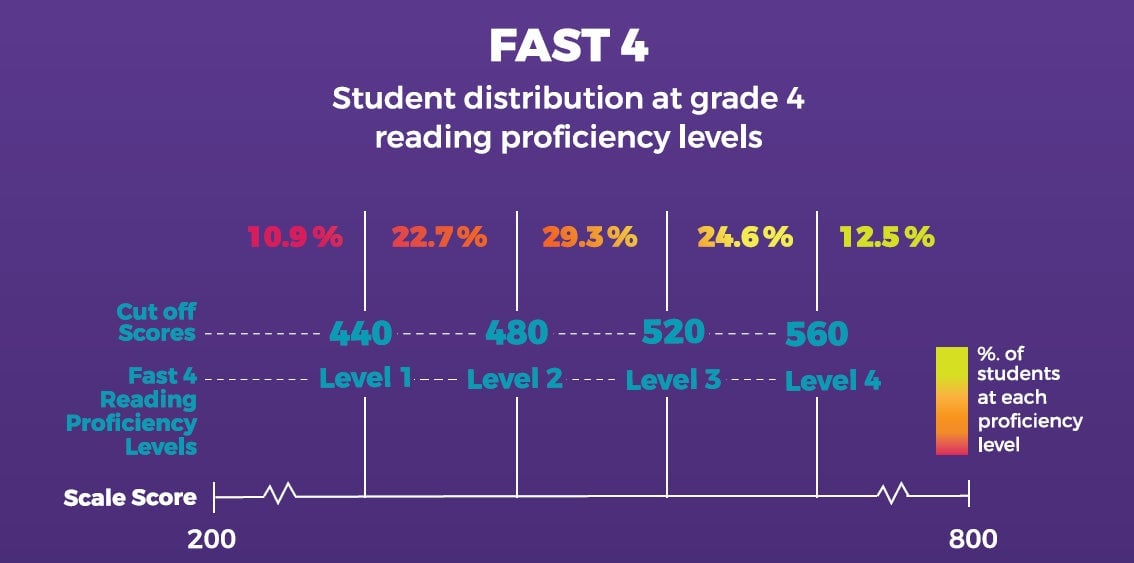

But a new study on the reading proficiency of students in private, unaided English-medium schools suggests this is hardly the case. While children around the world are expected to be independent readers by the end of grade three, the study, conducted by non-profit Stones2Milestones, found that only 12.5% of Indian students in grade four showed full and detailed understanding of texts in a reading assessment. And of the students surveyed from grades five and six, just 2.7% recorded good comprehension skills.

This matters because research has shown that a student’s reading ability is the single-greatest predictor of their academic success, Stones2Milestones says. And in a country like India, where English is an aspirational language that can determine careers and incomes, poor reading comprehension can have life-long consequences.

“When you look at the Indian context…there are larger implications in their academic lives. One thing is that math is essentially a reading problem; once a child reaches grades 7-10, he ends up not being able to comprehend maths problems, rather than not being able to understand the concept of maths,” Nikhil Saraf, co-founder of Stones2Milestones, told Quartz. “And everything that we do post a certain age is in English—interviews are in English, the CAT, SAT, MAT, GMAT, and GRE are in English. That compounds the whole thing,” he added.

Gurugram-based Stones2Milestones was set up in 2015 to promote reading in India. For the study, which was launched in September last year, the organisation used the FAST reading assessment, a 40-minute multiple-choice online diagnostic test designed in India to test the comprehension and vocabulary of students in grades four, five, and six. It was administered to 19,765 children in 20 states via 106 urban and semi-urban schools that volunteered to take part in the study.

The results show that nearly 11% of students in grade four fell short of even the lowest reading level on the FAST assessment’s scale for that grade. At this lowest level, students should be able to recognise and retrieve explicitly stated information and understand the meanings of simple words. But the fact that many of the students surveyed couldn’t do so suggests that they were moving from one grade to the next without learning what they should have, making them all the more likely to fall behind later on, Stones2Milestones says.

“What we’re finding is children are able to do the surface-comprehension kind of questions. They’re not able to do deeper comprehension tasks, (though) this is what they would need to make sense of any unfamiliar text that comes their way,” said Aditi Mehta, head of content, training, and impact at Stones2Milestones. “The assumption that private schools (are) doing better than government schools is deeply tested as part of the process.”

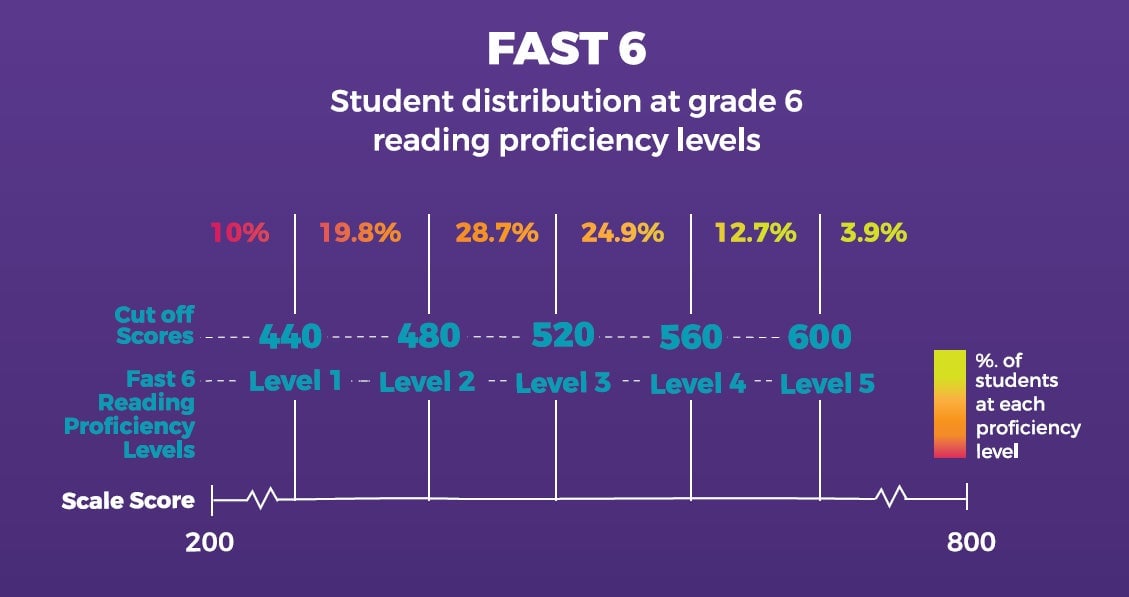

Among students of grade five, only 2.1% showed advanced vocabulary and comprehension skills, while nearly 13% fell short of the lowest reading level. And among those from grade six, just 3.9% scored enough to meet the highest reading level, while 10% fell below level one.

There are a number of reasons for this, including the way English is taught in schools in the first place. But Stones2Milestones believes the biggest concern is India’s overall approach to reading, which is rarely identified as a priority—both at school and at home.

“Reading for pleasure and for purpose is not as widely celebrated as it should be. A child sees going to the library as a punishment,” Mehta explained. “We don’t expressly teach reading in schools, and so children who don’t have a home environment where reading is celebrated will never catch up,” she added.

In fact, reading at home in particular can make a big difference, the study shows. After completing the FAST assessment, students had to answer six questions about their reading habits outside school. The researchers found that for grades four and five, the mean test score was significantly higher for students who read English books at home, often with others in the family, almost everyday or at least once a week.

So, one part of the solution is getting Indian parents to prioritise reading, making it accessible by using reading apps, for instance. But schools and educators need to do their part, too.

“What we can do about it is have an ecosystem-based approach to make sure teachers know how to teach reading. Schools need to pay special attention to how libraries are structured, and parents need to use every resource available to make reading fun, and accessible, and a bonding experience for their children,” Mehta said.

Until this happens, even privately educated children could face an uncertain future.