An evaluation of college teachers in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) last week showed that some of the professors lack even basic knowledge of the subjects they teach. For instance, an economics professor did not know what “audit” means or what “IMF” (International Monetary Fund) stands for.

There was a similar revelation among students in Bihar in June. In this state, neighbouring UP, the class 12 topper said political science involves cooking.

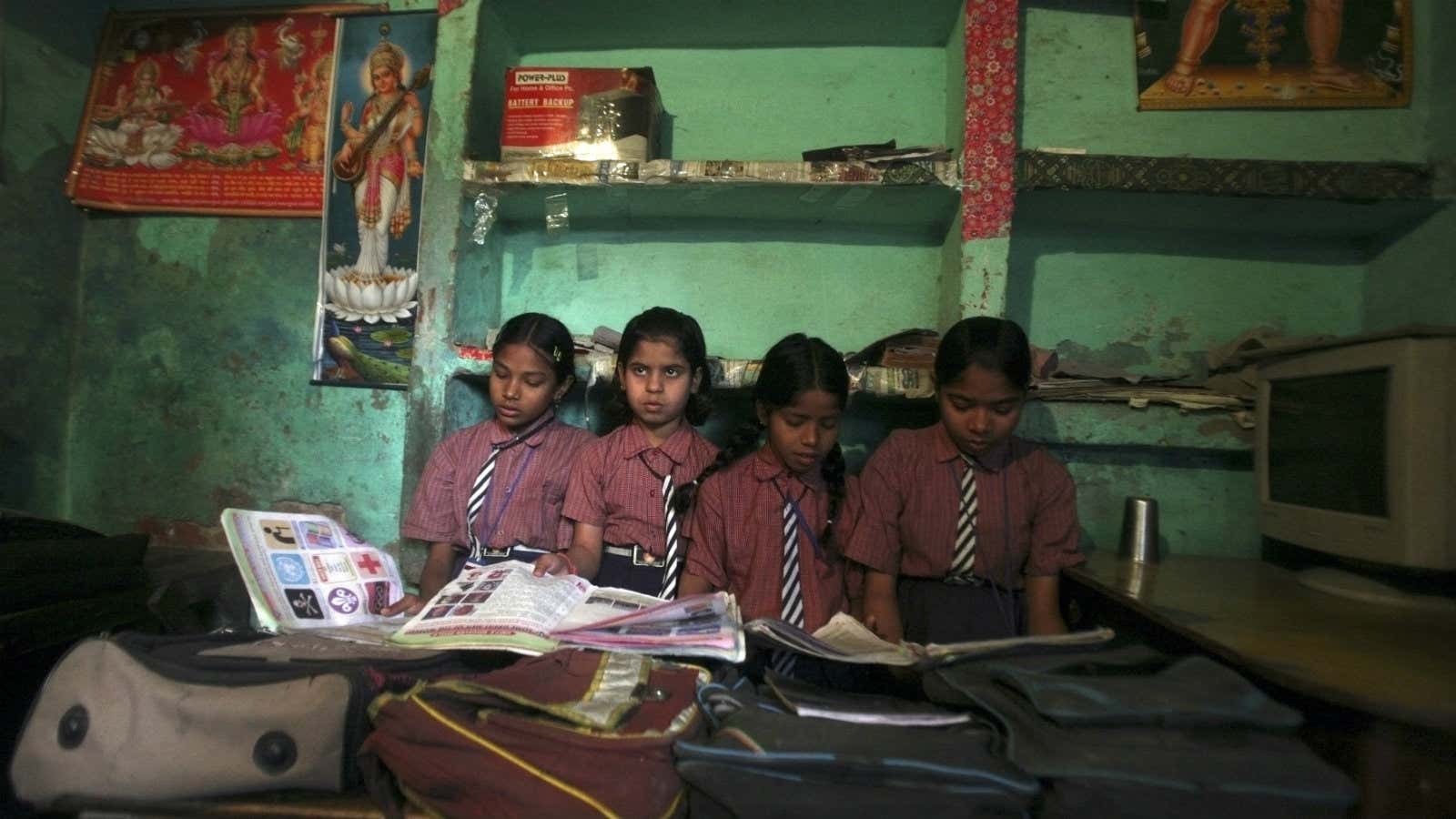

Such instances are proof of the grim condition of education in India.

Even the Narendra Modi government has come to acknowledge the mess, with a recent report by the human resource development ministry pointing out various challenges.

From dismal quality to lack of research, the report, proposing draft guidelines (pdf) for the National Education Policy 2016, explains the dire need to fix these problems.

Low enrollment, high dropout

A large number of children still don’t go to school. And many of those who do, drop out at some stage.

In the age group of 6-13, the percentage of children out of school has dropped “significantly” since 2000, the report says. But, in absolute terms, the number is still high in India. Besides, enrollment rates in upper primary education (class six and seven) and secondary (class eight to 10) are still very low.

“India has the second-largest higher education system in the world. Although Indian higher education has already entered a stage of massification, the gross enrolment ratio in higher education remains low at 23.6% in 2014-15,” the report said.

The country is home to the highest number of illiterates—in 2011, it was 282.6 million people aged over seven.

Poor quality

The quality of education in India has long been criticised. Not only is it based on rote learning, but there is also hardly any practical knowledge gained by students. Many students can’t even do basic arithmetic even in higher classes, studies have found.

Of the 2,780 colleges accredited by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC)—a government body formed to assess and grade educational institutions—only 9% have an A grade currently. Some 91% fall in the average or below average categories, the report says.

No skills

With its economy growing at 7.6%, India wants to be the next economic superpower. Modi himself dreams of making it a manufacturing powerhouse. But an acute skill-deficit hampers the country.

The ministry’s report says that many graduates and post-graduates do not get jobs in their respective chosen fields. “The utility of higher education in assuring employment remains questionable,” it added.

By 2050, India will have some 1.1 billion working-age people—the highest in Asia-Pacific. If most of these aren’t employable, then there’s going to be a huge talent gap.

Outdated curriculum

One reason for both poor learning outcomes and lack of skills is the curriculum at Indian schools and colleges. The report says there’s a “serious disconnect” today between what’s taught and what’s needed in a “rapidly changing world.”

The existing curriculum does not foster creativity and innovation, nor does it enable critical thinking or independent problem-solving, the report says. Even the assessment processes and practices at schools and colleges are unsatisfactory, it says.

Teachers

Teachers simply aren’t well-equipped. Even their training programmes aren’t effective in a changing social, economic, cultural, and technological environment. There have been few initiatives to upgrade their skills or build synergies between teaching and research, the report says.

Besides, there’s also chronic shortage to deal with. “There exists a continued mismatch between institutional capacity and required teacher supply resulting in shortage,” the report says.

Educational inclusion

An often-ignored, but critical, aspect is whether education reaches everyone. The report says that disadvantaged sections still can’t access it.

“While there has been a rise in demand for secondary education… the spread of secondary education, remains uneven. Regional disparities continue, as do differences in access depending on the socio-economic background of students,” the report says.

Besides, the gender gap in adult literacy is high at 19.5 percentage points. Some 78.8% of male adults are literate compared to 59.3% of women.

Poor governance

Schools aren’t governed efficiently. Funds don’t reach educational institutions in time, the administration isn’t well-equipped, and implementation of policies is a key issue, the report says.

Lack of research

India boasts of producing some of the world’s best engineers and scientists. But its universities aren’t exactly a breeding ground for scientists and their research.

Universities need to encourage higher education institutions to engage with international faculty so that the quality of research back home can be improved, the report says.