Meet the gay couple who pleaded with India’s top court for the right to love

Cherished rights often come about because organizations and people have worked for years to make them happen. But they also usually depend—in the last mile—on a few people (paywall) deciding to step forward at great personal risk to push a country forward.

Cherished rights often come about because organizations and people have worked for years to make them happen. But they also usually depend—in the last mile—on a few people (paywall) deciding to step forward at great personal risk to push a country forward.

India’s landmark gay-rights victory today (Sept. 6), decriminalizing same-sex relations between consenting adults, involved both kinds of struggles. Earlier efforts involved a public interest suit brought by an HIV-prevention group, which won a celebrated but limited victory in 2009 that was overturned four years later. Today’s win began with a petition that was filed in 2016 (pdf) and referred to a larger constitutional bench in January, and it depended in large part on a couple who’ve been together for nearly a quarter century.

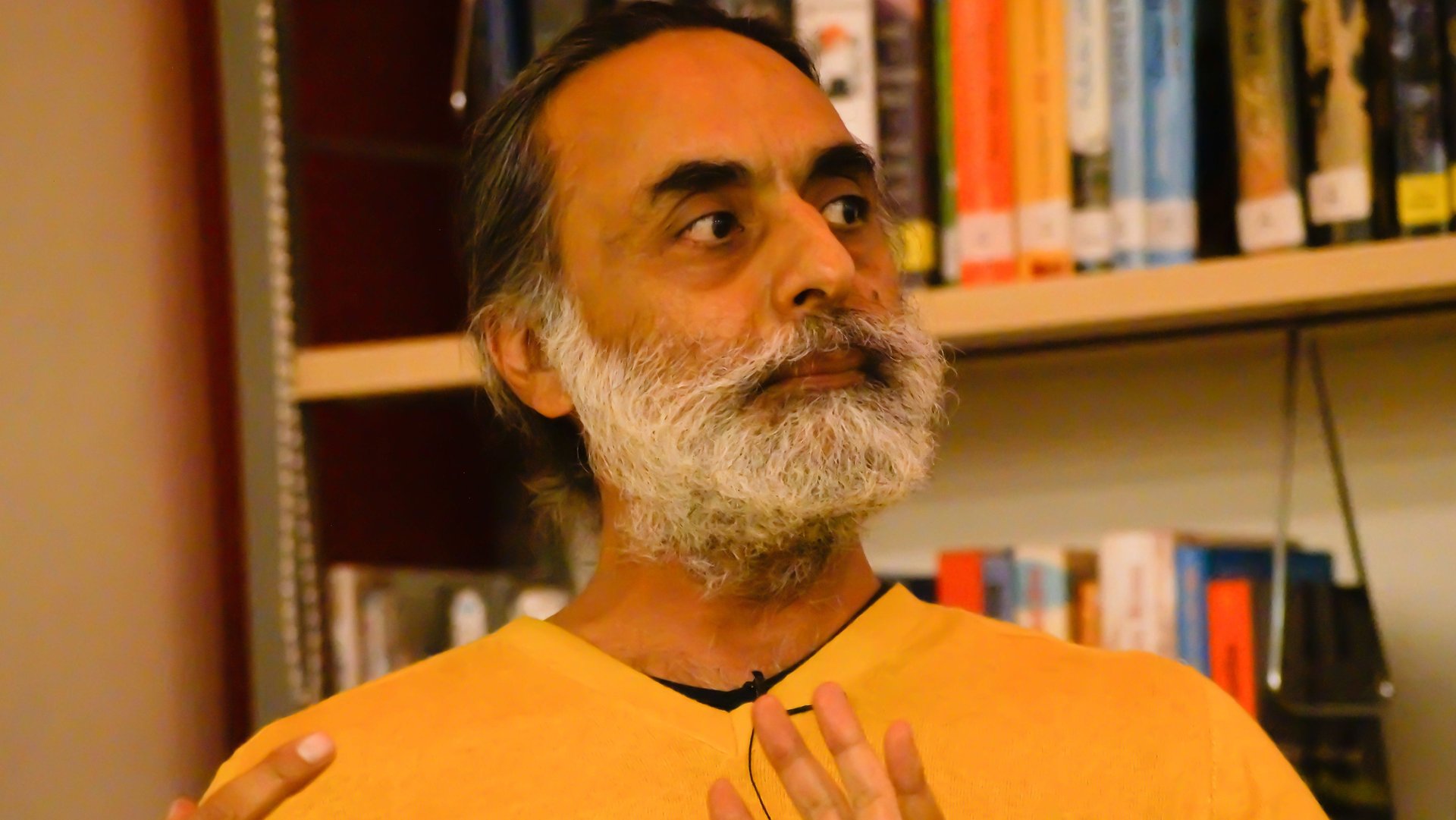

Navtej Singh Johar, 59, a classical dancer and a yoga teacher from the Punjab town of Chandigarh, and his partner, journalist Sunil Mehra, 63, never planned to be a test case. They focused on their own lives and passions. Johar knew early on that he wanted to be a dancer, and trained in classical Bharatanatyam, winning a top Indian dance honor in 2014. Mehra wrote for leading Indian publications about women’s rights, the threat to coral reefs off India’s coasts, and at times, his own experiences being a gay man in India.

The two became a couple, according to the Indian Express, after Mehra was assigned in 1994 to write a profile of Johar. After meeting the dancer, he came back to the office to tell his editor he wouldn’t be able to do it objectively. Six months later the couple moved in together, and have been together ever since, at one point opening a yoga and dance studio in Delhi. It was through the yoga studio that they befriended a pair of lawyers who would eventually help persuade them to be at the forefront of a new effort to tackle Section 377, a colonial-era criminal statute that made “unnatural sex” punishable by between 10 years in jail and a life sentence. That made it risky to be openly gay because of the scrutiny people could draw from the police.

The petition says that the couple managed to live together for more than 20 years with the support of family and friends. It also said that though Mehra had been targeted at times for being gay, he never reported it to the police for fear of being targeted under 377. Still, because of class privilege, Mehra and Johar were unlikely to face the kind of blackmail or extortion other LGBT men and women encounter in India, and could likely have continued on with their lives fairly peacefully. They could have rejected the idea broached by lawyers Menaka Guruswamy and Arundhati Katju that they bring a new, more personal plea before the top court, grounded in their constitutional rights as Indian citizens. Instead, they decided to put their own lives on hold, and petition the court to declare 377 unconstitutional. Others, including prominent restaurateur Ritu Dalmia, hotelier Aman Nath, and businesswoman Ayesha Kapur, also stepped forward (paywall).

Mehra puts their decision like this, in an interview with the Guardian:

We have been OK. I am 63—we have lived our lives. We had fought for our bit of sun and we found it. It was more for all those who didn’t have our class privileges, education, intellect, money and connections to insulate them. It was so that these other lives could be lived in the sun, rather than in burrowed, dark spaces.

It was a message Guruswamy echoed in July before the court, where she was representing a group of LGBT students whose case had been linked to Johar and Mehra’s. She recounted the history of the couple’s relationship, and told the court the case was not about sex, but about love, and most of all, about the future.