Twenty-four years, and a lifetime of insults. That’s what it took Nambi Narayanan to clear the taint of spying against his own country.

It didn’t help that the veteran scientist was acquitted by courts just two years after the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) spy scandal broke in 1994. The case trudged on for decades, blighting reputations and livelihoods—but he fought back relentlessly.

“(My children) told me if I die, they will forever be known as children of a spy. They told me I was the only person who can prevent such a disgrace on the family. It was then that living to fight this became a necessity for me,” Narayanan, now 76, told The Economic Times newspaper last week.

He was speaking to the newspaper after the supreme court of India on Sept. 14 granted him a compensation of Rs50 lakh ($69,000), even allowing him to seek more from the state government of Kerala, saying the entire prosecution had been borne out of “fancy” and had been “malicious.” The judgment reinforced his innocence and the acquittal granted long ago.

The case, in short, involved Narayanan and his colleagues being accused of passing on top secret information on the Indian space programme to Pakistan through two Maldivian women.

In hindsight, the entire scandal comes across as a brew of local politics, international manoeuvres, and police inefficiency.

The background

By 1994, India was just emerging out of the shadows of the Cold War.

Being technologically dependent mostly on the Soviet Union until recently, the country was now on its own. Yet, it had by then developed the polar satellite launch vehicle (PSLV), the sturdy platform that went on to become the workhorse of India’s space programme. Narayanan, then a senior ISRO scientist , had served as the director for two of the project’s four stages.

He was also in charge of the space agency’s cryogenic space engine project. Cryogenic engines use liquefied fuel to propel rockets to greater heights, a technology that, according to the US, could have military and possibly nuclear applications. Earlier, the US had sabotaged India’s deal with Russia to obtain two cryogenic engines. So now, Narayanan was put in charge of building an indigenous one.

Lift-off

On Oct. 20, 1994, the Kerala police arrested Maldivian native, Mariam Rasheeda, for allegedly overstaying her visa. She was reportedly in Kerala to get her friend and co-national Fauzia Hassan’s child admitted into a higher education course in the state.

The police are said to have found in Rasheeda’s phone records calls to Narayanan’s junior colleague D Sasikumar. He was arrested shortly after, and so was Hassan. This was followed by the arrest of a businessman from Bangalore (now Bengaluru), a representative of the Russian space agency Glavkosmos.

Narayanan’s arrest came on Nov. 30, 1994. Interestingly, on Nov. 01, the scientist had put in his application for voluntary retirement.

Soon, the Intelligence Bureau (IB), India’s internal intelligence agency, got involved, citing threats to national security. Narayanan’s house was searched and 75 kilograms of “classified” ISRO documents, which he was supposedly selling, were found there. Senior police officials deemed close to K Karunakaran, the then chief minister of Kerala, too, were incriminated in the case.

As public pressure mounted, the Kerala government transferred the case to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), India’s premier investigation agency, in December 1994.

Hereon, the case began to unravel.

In May 1996, the CBI submitted its investigation report to a Kerala court, dismissing the charges against the accused as baseless. ISRO, for instance, clarified that it did not classify any of its documents. “…It was usual for scientists to take the documents/drawings required for any meetings/discussions to their houses for study purposes,” the CBI report said.

It was clarified that Hotel Manor in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala’s capital, where Sasikumaran allegedly met a Pakistani intelligence officer in 1990, came into existence only in 1991.

The CBI accused the Kerala police’s special investigation team of being unprofessional in its investigation and recommended disciplinary action against the probe officials.

However, successive Kerala governments failed to pursue any action against the said police officers and, instead, even unsuccessfully tried to probe Narayanan and his co-accused again.

The media and the political opposition in the state, too, were having a field day with the scandal.

Missiles out of nowhere

Even though there was no case to be made, fallout from the scandal changed many personal and political trajectories.

Karunakaran, for one, had to resign. Narayanan was branded a traitor. His family was subjected to targeted harassment. Even ISRO’s reputation was dented, with its buses vandalised and its scientists’ kids facing insults in school.

Narayanan has also said that he was tortured during the 50 days he spent in police custody. He says he was beaten and slapped as his interrogators pressed him to just cough up a Muslim name—any Muslim name.

He maintains that India’s cryogenic space engine programme was set back by a decade, though this claim is countered on the grounds that the scientist had already chosen to retire before he was arrested.

On its part, the supreme court was just shy of admitting a conspiracy against Narayanan: “It is not a case where the accused is kept under custody and, eventually, after trial, he is found not guilty…The criminal law was set in motion without any basis. It was initiated, if one is allowed to say, on some kind of fancy or notion.”

There is no end to speculation as to who was behind Narayanan’s false prosecution.

Mariam Rasheeda, the Maldivian native whose arrest initiated the scandal, had said that one of the investigating officers in the case had sought sexual favours from her, and decided to frame her for espionage when she refused his advances.

Karunakaran’s political opponents—within his own party—are then said to have seized on the opportunity to get him replaced with their leader AK Antony. “Let the judicial (committee) go ahead. I don’t want to comment before that,” Antony told Quartz in the wake of last week’s supreme court verdict.

A more disconcerting theory, which Narayanan himself alluded to in his book, Orbit of Memories, was that American intelligence had infiltrated the IB, setting it on him to sabotage India’s space research:

My investigation showed that the spy case was the illegitimate child of the US-French agencies with the intention of burying me and the ISRO in the cemetery…The spy case saw a Maldivian woman being framed as a spy to carry secrets that never existed by police officials, politicians and journalists who knowingly or unknowingly fell for the plot of the CIA.

Narayanan later backtracked on this claim. He says he is hopeful that the new committee which the supreme court has set up in response to his demand for disciplinary action against the officers who investigated the case will help him find answers.

“…the fight is over, there is nothing further to do,” the Deccan Chronicle newspaper reported Narayanan as saying on Sept. 17.

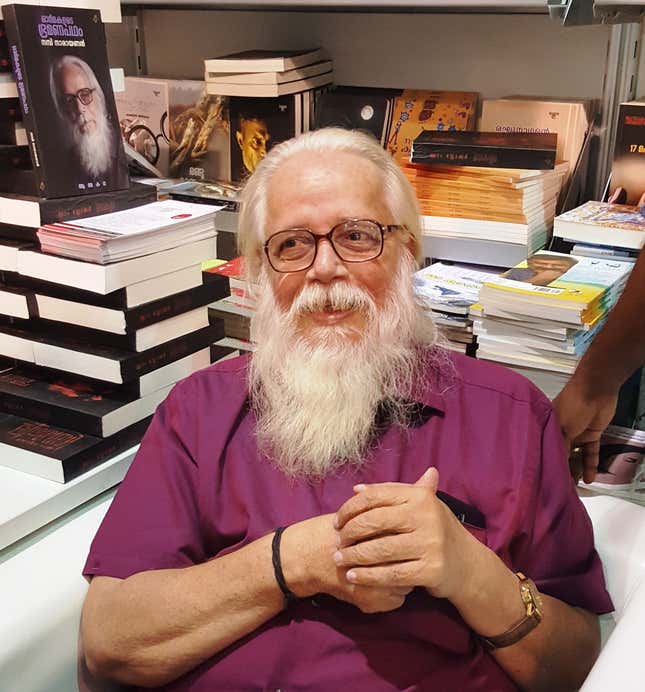

Inline image by by Vicharam on Wikimedia Commons, licenced under CC BY-SA 4.0.