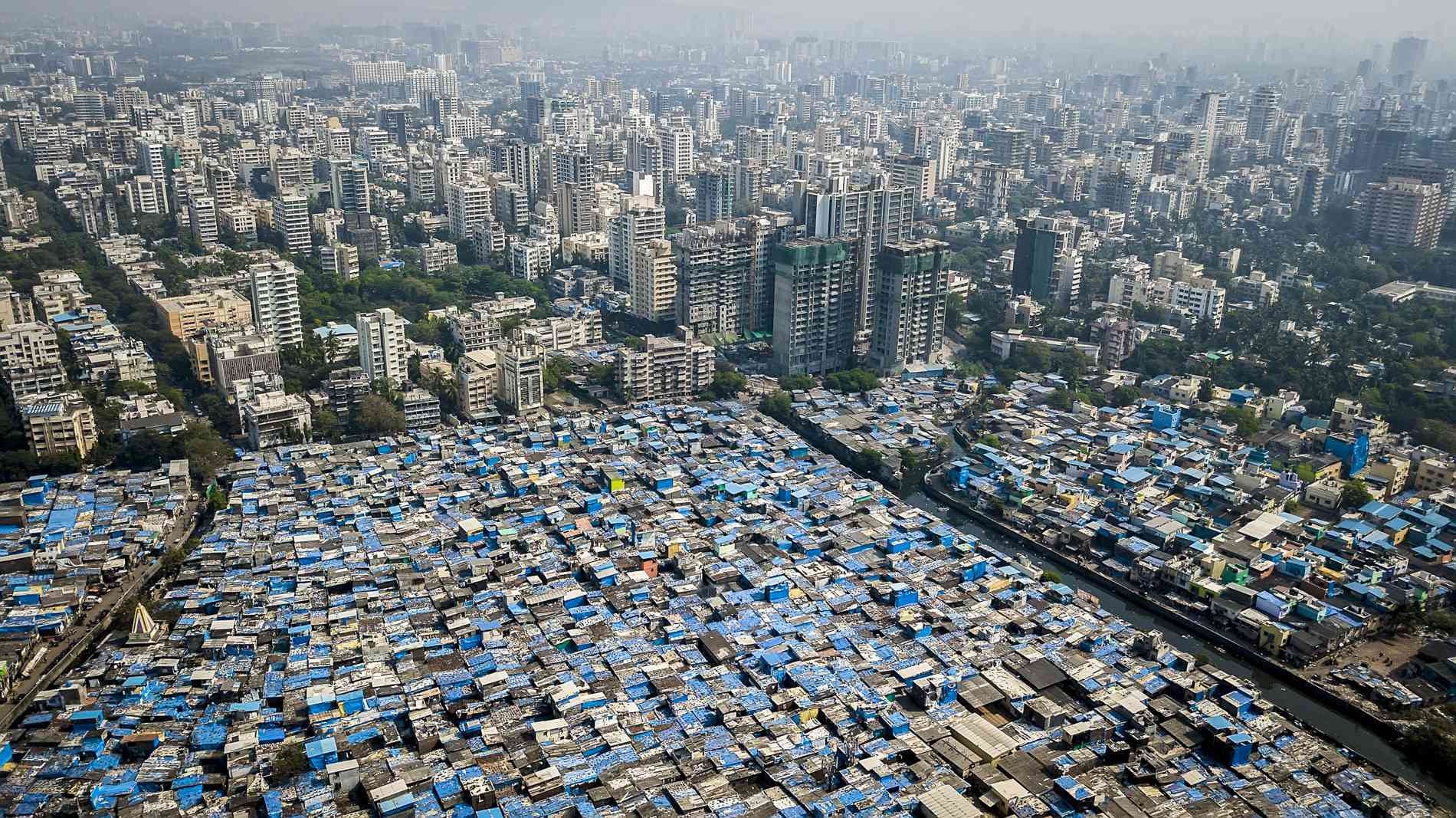

Drone photos capture the staggering inequality in Mumbai

Mumbai’s startling inequality presents itself in a variety of ways. It is visible when driving down the busy roads and from the windows of its suburban trains—swanky high-rises often stand in proximity to a sprawling network of shanties. But the clearest view of the disparity comes from up in the sky.

Mumbai’s startling inequality presents itself in a variety of ways. It is visible when driving down the busy roads and from the windows of its suburban trains—swanky high-rises often stand in proximity to a sprawling network of shanties. But the clearest view of the disparity comes from up in the sky.

It was from this vantage point that photographer Johnny Miller recently trained his lens on Mumbai. His images, focusing on Dharavi, Mahim, and the Bandra Kurla Complex, show a dense and divided city with clear lines separating the poor from the rich.

These photographs are a part of Miller’s Unequal Scenes project, which he describes as “a visual exploration of inequality around the world by drone.” Over the past two years, Miller has covered parts of South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, the US, and Mexico, apart from India.

Miller, who was born in the US, moved to Cape Town in 2012 to do his master’s in anthropology. It was here, four years later, that his journey with Unequal Scenes began.

The inequality in South Africa, says Miller, was “impossible to ignore.” Close to half a century of Apartheid, which ended in 1994, meant the divide was not just a byproduct of uneven economic growth—it was a systemic practice. The divisions were social, economic, and architectural. Black and coloured people had to live in separate areas from the whites, usually further away from city centres and in extremely cramped spaces, as hardly any land was made available to them. The impact of this segregation continues to be felt. Protests over affordable housing and other amenities are a frequent occurrence. What Miller noticed, however, were the physical signs of the era of segregation—the barriers in the form of rivers, wetlands, or barren land that continue to divide rich and poor areas in many parts of South Africa.

“From the minute you land in Cape Town, you are surrounded by shacks,” said Miller. “…But I thought it was strange how easy it was to become habituated to inequality. To drive past these shacks every day, but not really think about it, or do anything about it. So I decided to take my drone and focus on the problem— and try to change people’s perspective, literally with an aerial view of the problem as I saw it. And one day in April 2016, I did just that—and the project was born.”

Miller finds the aerial perspective to be the most effective way to capture the disparity. “The images that I find the most powerful are when the camera is looking straight down—what’s known as [the] nadir view, looking at the actual borders between (the) rich and (the) poor,” he said. “Sometimes this is a fence, sometimes a road, or a wetland—with small shacks or poor houses on one side, and larger houses or mansions on the other. Whatever it is about the composition of those photographs, they are extremely powerful to people.”

A video uploaded on Miller’s YouTube channel in 2016, for instance, showed the stark contrast between Cape Town’s low-income Masiphumele area and the elite Lake Michelle township, the two areas divided by a wetland.

From South Africa, Miller went on to document scenes of such inequality in Tanzania, Nairobi, Mexico City and several parts of the United States, including Seattle, San Francisco, and Detroit. The American project provided an interesting perspective on how inequality manifests itself in developed countries.

Miller relies on extensive research to identify where to take photographs. “This is a combination of census data, maps, news reports, and talking to people,” he said. For Mumbai, he referred to slum maps prepared by architect PK Das. Miller has been to Mumbai a couple of times, and though he finds the city “incredibly busy,” it isn’t overwhelming. “In fact, I feel very comfortable there,” he said.

Once he zeroes in on an area, Miller uses Google Earth to get a sense of the geography and maps out a flight plan. “This includes taking into account air law, air safety, personal safety, battery life, range, weather, angle, time of day and many more factors,” he said. “Not to mention all the logistics that go into taking aerial photographs around the world—hotels, rental cars, different languages. Oftentimes, I’ll have a friend, or a colleague, or even a co-worker who will help me out—but sometimes I’m totally on my own.”

Photography wasn’t what Miller always set out to get involved with. A student of political science, he first picked up a camera when he was 29, and taught himself how to use it. According to an interview in The Huffington Post, Miller discovered drone imagery by chance, while taking a video of his friends who were with him on a hike to the Table Mountain in Cape Town.

Miller believes photography is a powerful tool because it creates a literal as well as emotional distance. “This is also why I think Unequal Scenes is important—it allows us the distance to really reflect on the fact that we have allowed our societies to become so unequal. Traditional portraiture and photography on the ground rarely allow for that sort of contemplation. This is really what I intended and desired to happen—that the photos would spark conversations, and through these conversations, we could begin to understand the scope of the problem, and through that understanding, we could develop solutions.”

Miller’s work has been covered by the global media and won him several awards. He established africanDRONE.org, a non-profit organisation, through which he promotes and supports drone journalism and other related initiatives. According to its website, drones boost storytelling by going “where humans cannot, giving journalists cheaper and safer access to conflict zones and other hazardous areas, from the epicentre of a natural disaster to conflict zones, (and) to industry’s toxic no-man lands”.

With additional inputs from Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri. We welcome your comments at [email protected].