India’s data localisation plans could hurt its own startups the most

India’s push for data localisation won’t abate anytime soon. And neither will the resistance by international lobbyists.

India’s push for data localisation won’t abate anytime soon. And neither will the resistance by international lobbyists.

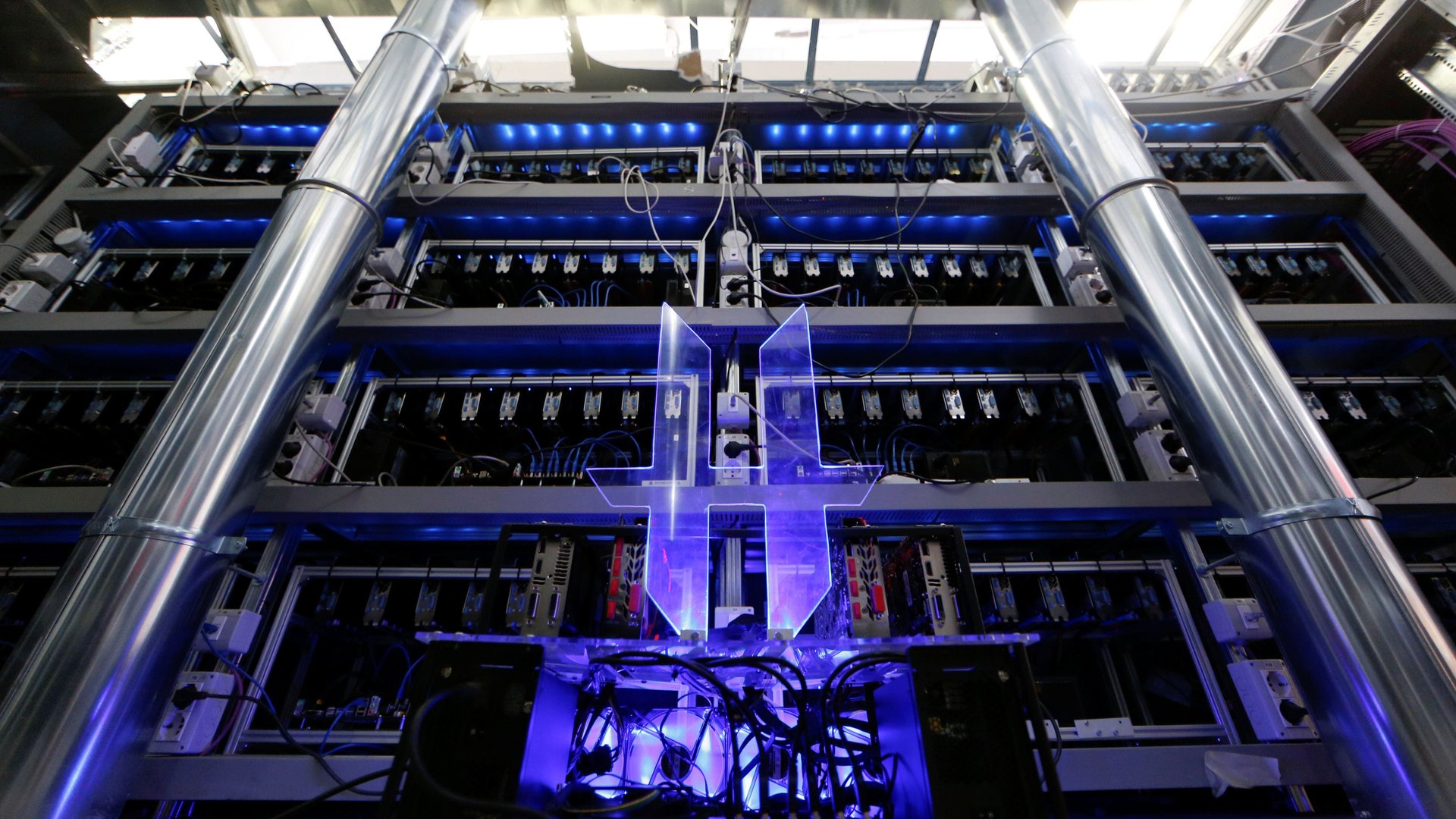

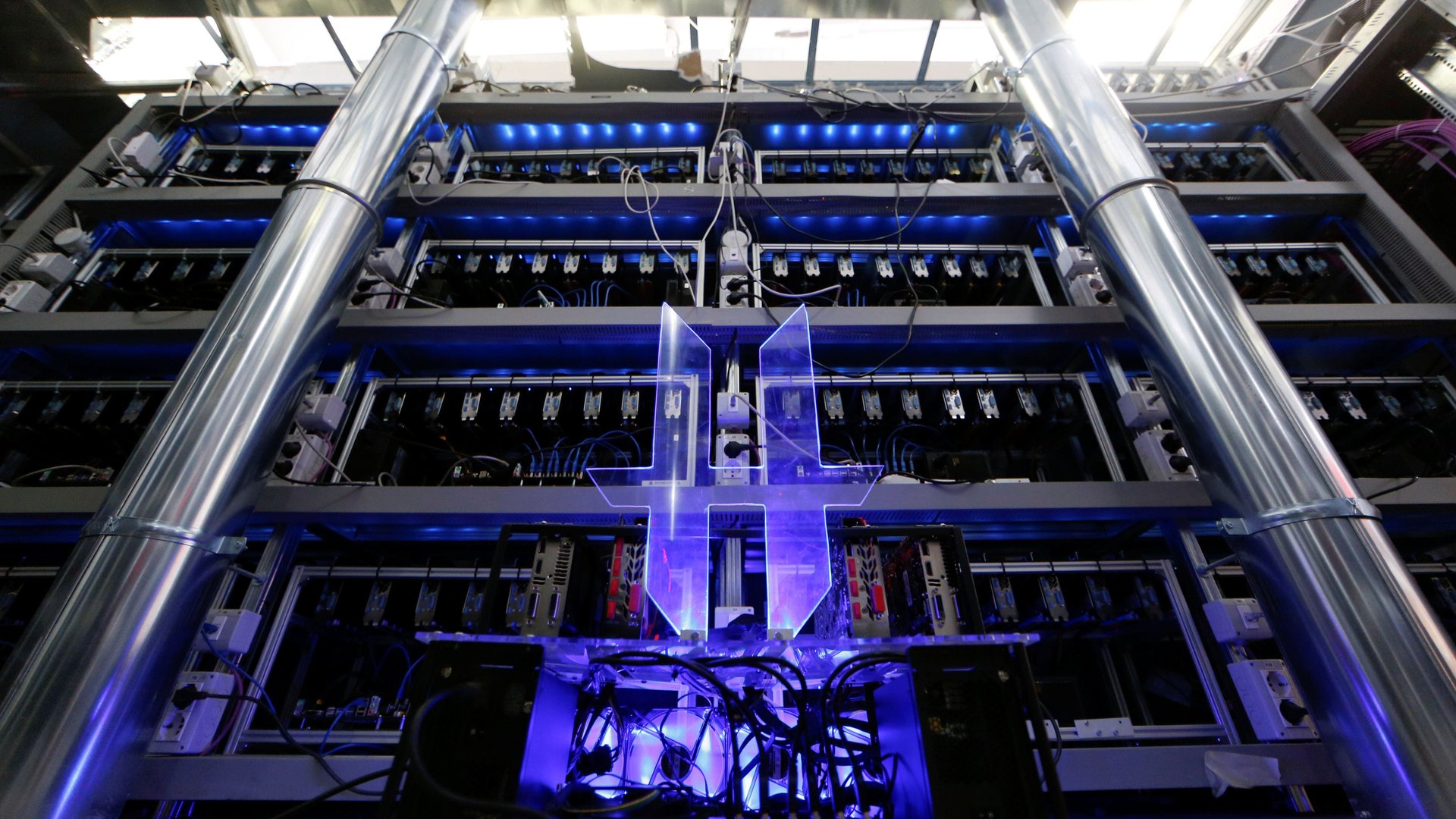

Data localisation is a key area covered by the Srikrishna Committee’s draft bill, which, if passed, will become India’s first privacy law. Released this July, the draft bill includes provisions that require a copy of all online personal data of Indians to be stored within the country, and certain “critical personal data” to be processed only in India. Also, the Reserve Bank of India has issued a circular mandating all payments companies to store their Indian customers’ data locally.

While some major companies, such as Facebook-owned WhatsApp, have already lined up to comply, many global players, including US trade groups that represent companies such as Amazon, American Express, and Microsoft, have lobbied against data localisation.

On Sept. 26, up to 10 industry bodies and organisations together wrote to India’s law and IT minister, Ravi Shankar Prasad, requesting the removal of localisation requirements from the draft bill. The signatories included the US-India Business Council (USIBC), the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI), DigitalEurope, and the Japan Information Technology Services Industry Association (JISA), among others.

Allied for Startups, a Brussels-based advocacy group, also signed the letter. The organisation is a global network that helps startup communities understand and effectively interact with public policy and governments.

In an email interview with Quartz, Lenard Koschwitz, director of Allied for Startups, shared his thoughts on data localisation and the damage it stands to do to India and the global startup economy. Edited excerpts:

According to research, what are the overall economic effects of data localisation?

Where data localisation is happening, economies suffer. According to a 2016 study by the European Centre for International Political Economy, the EU’s GDP would gain €8 billion, the same amount as all EU free trade agreements, by abolishing data localisation measures. On the other hand, with data localisation measures as strict as those proposed in India, the EU would lose over €50 billion annually: 0.5% of its entire GDP. If we assume similar effects, India could lose nearly $8.4 billion (over Rs62,000 crore) annually.

(Note: Data localisation will largely be abolished in the EU around next May, when the recently passed regulation on the free flow of data will begin to be enforced.)

What would mandating data localisation in India mean for people and businesses?

The consumer and the society at large will notice data localisation measures through the cost and the number of services available. Data localisation is a bit like having a national internet, a splinternet. Rather than choosing the best, fastest, and cheapest providers to store data, the choice is limited to domestic providers who have little incentive to provide superior services due to the lack of competition.

It might hinder Indian startups from growing globally and selling abroad because the cost for servers and cloud infrastructure may give them a competitive disadvantage. For startups from Europe, data localisation measures could be a reason not to scale to India because of an additional burden and cost of storing data locally.

Without localisation, are there ways to protect sensitive data and ensure that law enforcement can investigate crimes?

Data security and integrity is best provided through encryption and clear legal frameworks. Let’s assume data is stored locally but encrypted, or that data required for a criminal investigation is stored in another territory, where there are strict data localisation laws (which prohibit the flow of data outside the country). In both scenarios, criminal investigations might become impossible and the economy may suffer. Regardless of the actual location of data, the government should invest in legal frameworks and judicial oversight to provide clarity for law enforcement authorities, companies, and citizens alike.

What would be the ideal way forward for India when it comes to data localisation and privacy policies?

India is in an incredibly interesting situation right now. On the one hand, there is an incredible growth and uptake in digital services and entrepreneurship. On the other hand, India’s policymakers have the opportunity to examine what other economies, the EU for example, have done when it comes to data localisation and privacy. Two things are crucial for India to stay ahead of the curve. First, policymakers must believe in the transformative power of Indian entrepreneurs to succeed globally and allow those entrepreneurs to sit at the table and be part of decisions regarding privacy and data flows. Second, rather than simply copying foreign legislation, the Indian government could cut red tape and legal uncertainty for businesses while providing an adequate protection of data in a global context.