How a scheme to clean up India’s electoral list may have left out millions

A 2015 project that aimed to “purify” India’s voter base may have stripped millions of names from electoral rolls and collected data from citizens without obtaining informed consent.

A 2015 project that aimed to “purify” India’s voter base may have stripped millions of names from electoral rolls and collected data from citizens without obtaining informed consent.

The National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme (NERPAP), which took place over several months in 2015, was the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) attempt to use software based on Aadhaar, the controversial national biometric identity database, to flag duplicate voters’ names for deletion. Several recent reports, including by HuffPost India, The Wire, and Scroll, draw on internal ECI documents to investigate the programme.

According to these documents, which Quartz has also accessed, the ECI itself was worried about issues like coercion and wrongful deletion of voter names.

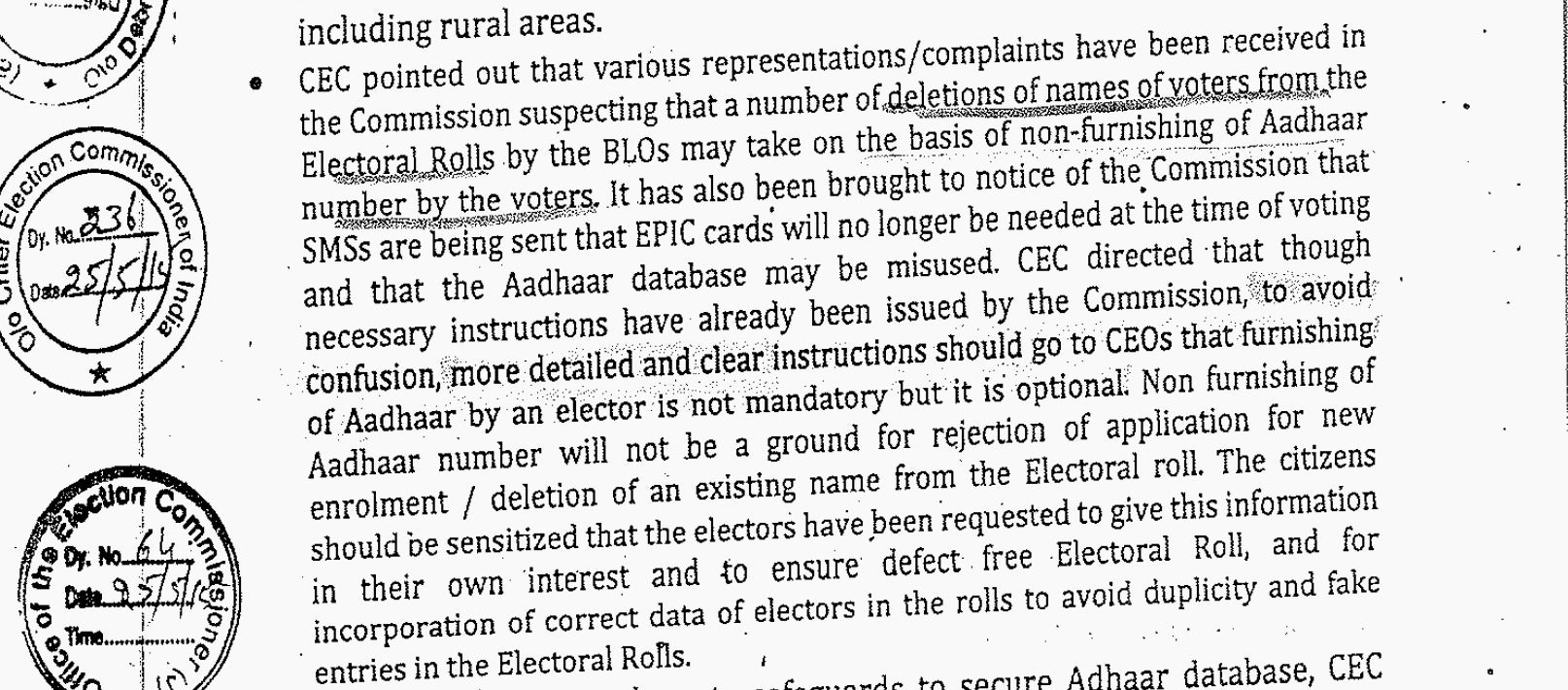

The minutes of an ECI meeting about NERPAP from May 2015, a few months after the programme began, record the chief election commissioner underlining that “various representations/complaints have been received in the Commission suspecting that a number of deletions of names of voters from the electoral rolls” because voters did not furnish their Aadhaar.

The record also indicates that some election officers were not fully informed of the fact that voters were not required to provide their Aadhaar numbers: “To avoid confusion, more detailed and clear instructions should go to CEOs that furnishing of Aadhaar by an elector is not mandatory but it is optional.”

The ECI stopped NERPAP in August 2015 after the supreme court issued an interim order that checked the spread of Aadhaar while the biometric programme’s constitutionality was still being challenged. But the damage may have been significant and lasting.

Aadhaar was never even meant to be an identification number only for citizens, but for all Indian residents. “A number for residents is actually converted into a tool for excluding citizens,” R Ramakumar, an economics professor at the Tata Institute for Social Sciences in Mumbai, told Quartz. “So the idea of citizenship itself is under question.”

A muddled process

NERPAP’s software worked by comparing state-level Aadhaar databases with electoral rolls to find entries that at least partially matched, Huffpost reported. Once an entry was flagged as a potential duplicate, an election official would reportedly be told to take steps to verify the person’s identity. If the voter could not be reached, the officer would recommend that the name be struck off the rolls.

The ECI maintained in an interview to Scroll that Aadhaar-Voter ID linkage was always done with consent. Email queries Quartz sent to both the ECI and the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), which administers Aadhaar, went unanswered.

The poll body seems to be attempting to renew the connection between Aadhaar and voter IDs. Even after the supreme court placed significant checks on the use of Aadhaar in late September, the ECI has supported a petition being heard in the Madras high court, calling for Aadhaar to be linked with voter IDs.

Disproportionate harm

“People without Aadhaar will be declared ghosts and their names are deleted without any warning, people who do not (or, cannot) link their Aadhaar numbers will face the same fate,” said economist Reetika Khera who has written extensively about how linking welfare programmes with Aadhaar leads to denial of benefits to the poor.

And others yet may be excluded from voting “if they experience any biometric enrolment/authentication issues.”

Drawing a parallel between voter ID laws in the US, Khera said attempts to compel Aadhaar linkage with voter IDs would disproportionately affect the oppressed. “Voter ID requirements tend to exclude the most disadvantaged groups,” such as the poor, the elderly and the disabled, she said.

For Indians, issues of voter-roll integrity have always been deeply tied to ones of social inclusion. A recent study of voter data in Karnataka found that Muslims were far more likely than average to not be included in the state’s voter rolls.

“In principle, there’s nothing wrong with requiring biometric ID for voting,” said Sadanand Dhume, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. “But it’s important to ensure that this is used only as a tool for identification, and not as a tool for exclusion of marginalised groups.”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.