Maps show how Bengaluru is expanding way too quickly for its residents

The home of India’s tech industry is growing rapidly. But basic government services have yet to catch up.

The home of India’s tech industry is growing rapidly. But basic government services have yet to catch up.

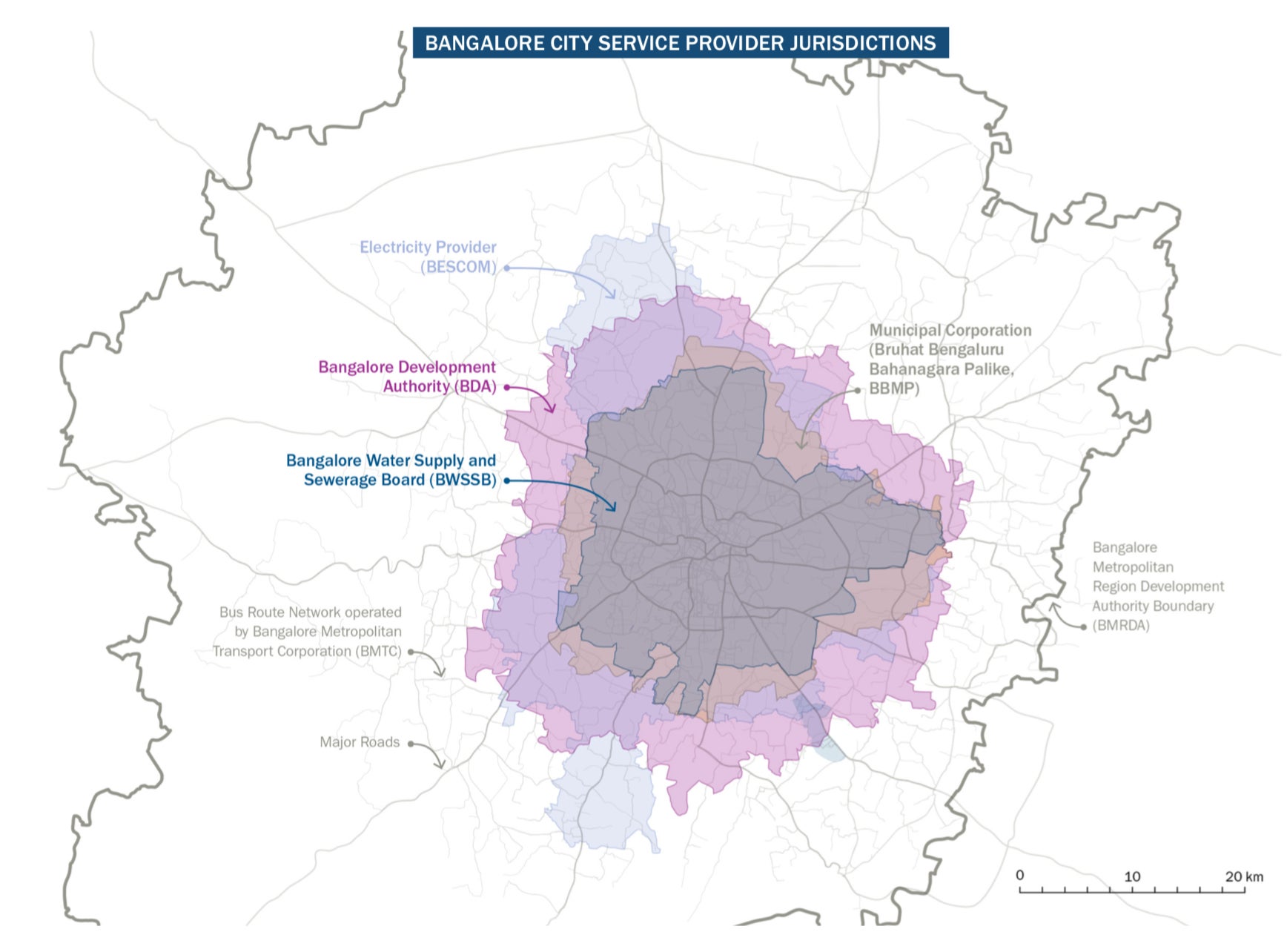

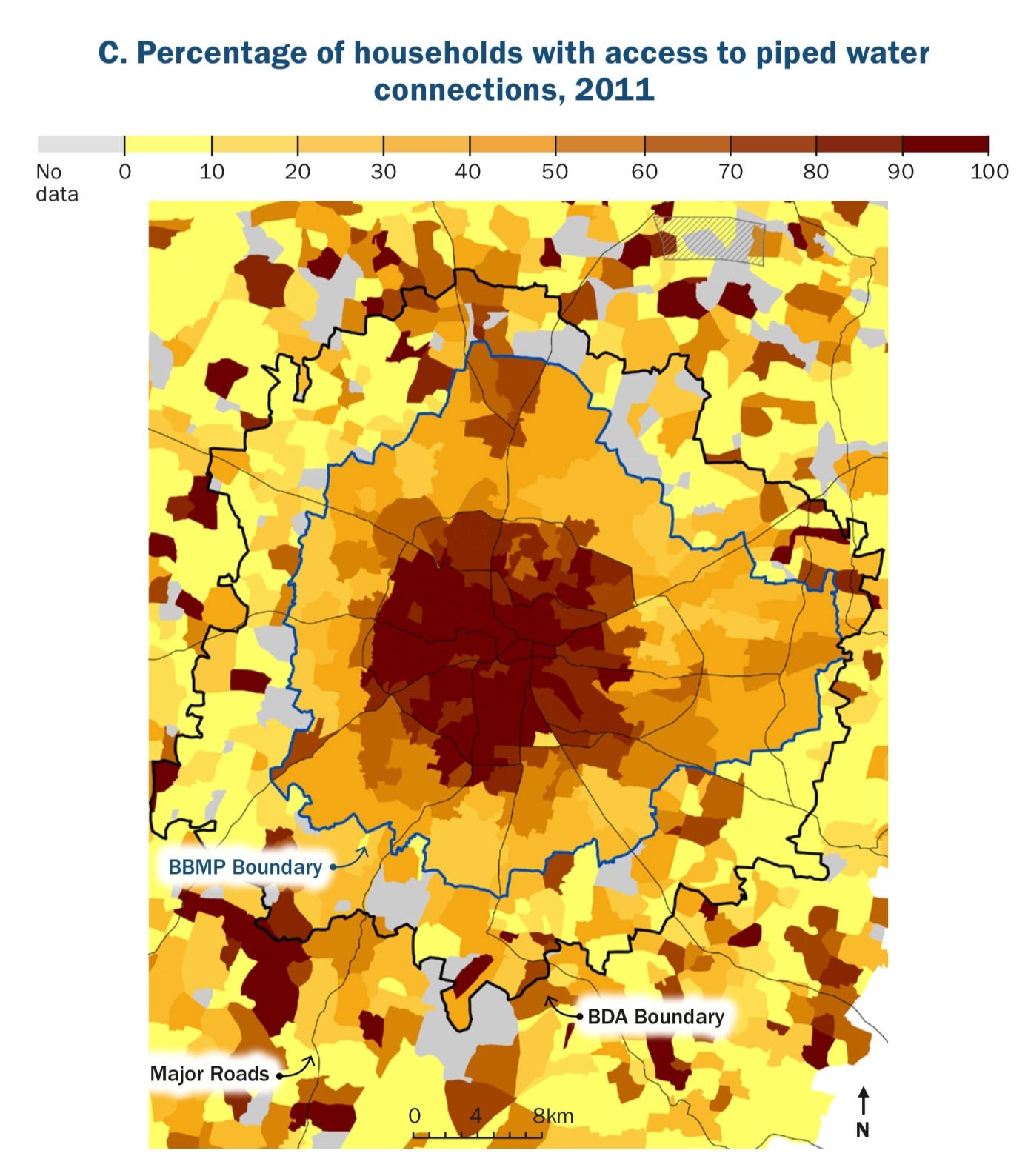

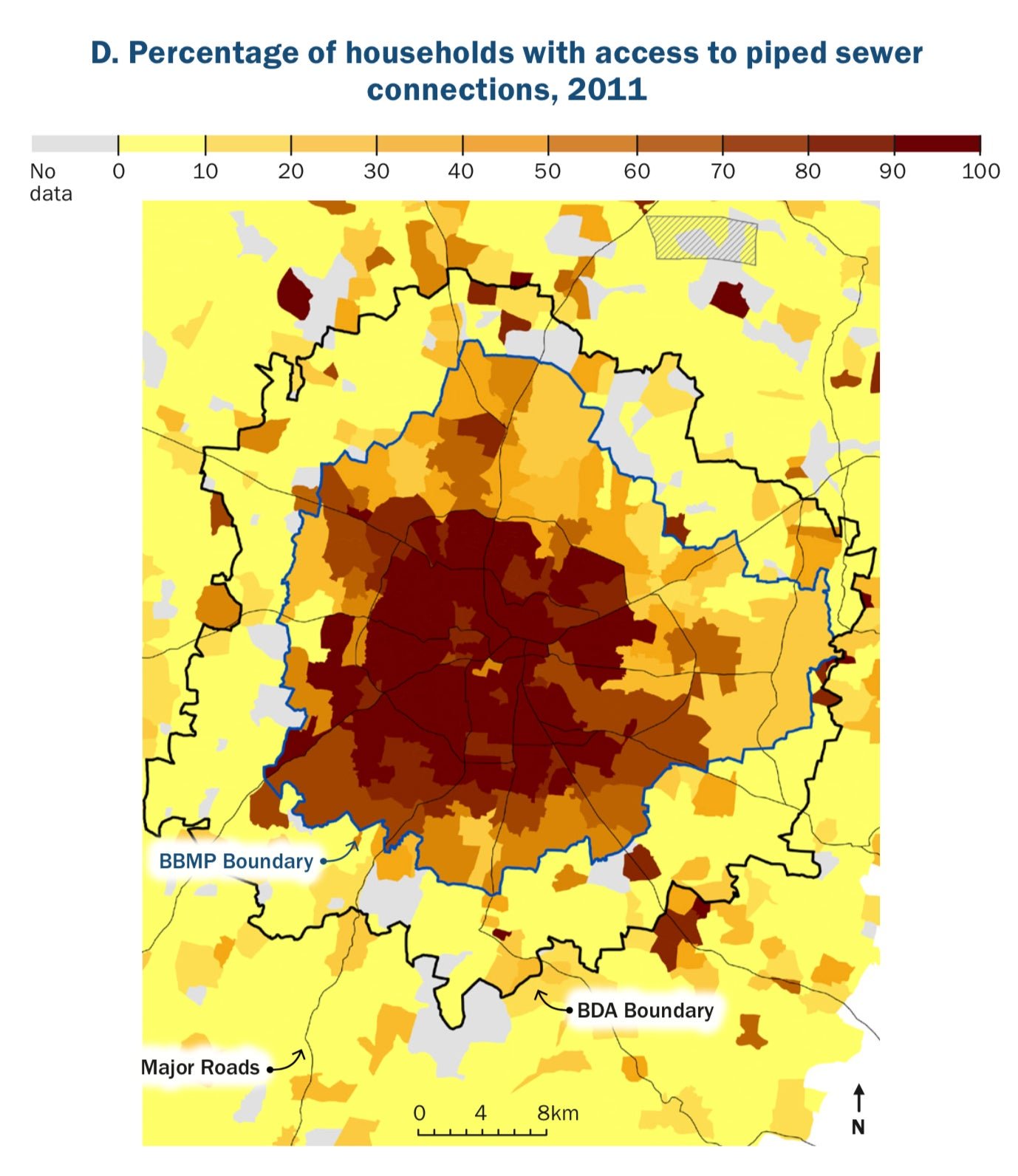

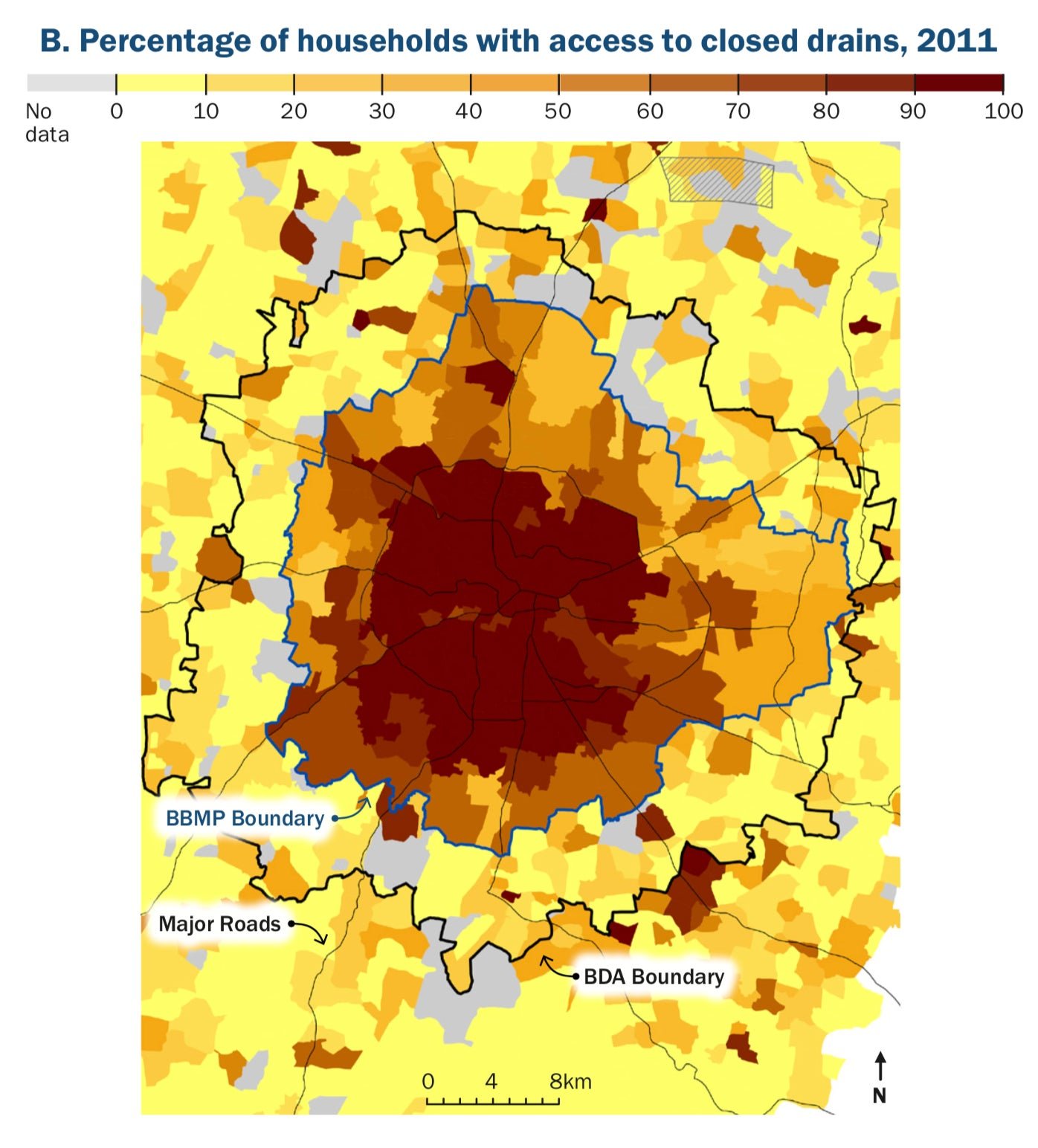

While most people in the southern Indian city of Bengaluru are settling around its periphery, state-owned companies that provide a range of amenities from electricity to water have not kept pace, with their jurisdiction limited to areas around the city centre, says a new study by the World Resources Institute, a Washington DC-based non-profit research organisation.

The study looked at cities across developing countries and found a familiar pattern. “Residents in areas without access to good quality urban services—housing, energy, transportation, water, and sanitation—must rely on alternate, costly, and often unsafe means of service provision,” it says. “As a result, between 25% and 70% of urban populations in the global South rely on informal arrangements to procure core services.”

Bengaluru’s peripheral areas either fall under rural service-providing agencies or are left to fend for themselves, said V Surya Prakash, managing associate at WRI India Sustainable Cities. For instance, “most houses in the outer areas draw water from the ground. Groundwater levels are drastically changing. It may provide for the next 15-20 years, after which it’s a very critical situation,” he said.

Traffic congestion has also worsened despite both a decline in population density—due to residents shifting to Bengaluru’s expanding periphery, where property rates are less expensive—and an expansion of the road network, Prakash added. This reflects that the public transit system hasn’t sufficiently connected the outer regions with the city centre, he said.

The study found such similarities across urban India: “In other places, such as the Indian city of Gurgaon (Gurugram) just outside of New Delhi, land acquisition from adjoining villages has led to hyperdevelopment characterized by gated communities, corporate buildings, and shopping malls. Property owners use private services in the absence of municipal services.”

Both government policies and property developers share responsibility for the outward expansion of cities. “As land in peripheral areas is more easily available and affordable, developers are able to achieve significant economies of scale by constructing large housing complexes,” the study says, adding that governments incentivise new townships and industrial corridors because these serve as an additional source of revenue.

It adds that “areas of new growth, areas of informal growth, or urban villages on a city’s periphery often lie within the planning jurisdictions of multiple local-level agencies (and sometimes regional, state, or rural agencies) that… do not coordinate on service provision. This creates significant governance challenges.”

Areas in the metropolitan Bengaluru region undergoing rapid urbanisation should be brought under a uniform jurisdiction to offset the lack of coordination between overlapping agencies, Prakash said.