Why India’s latest push for solar panel manufacturing may not be strong enough

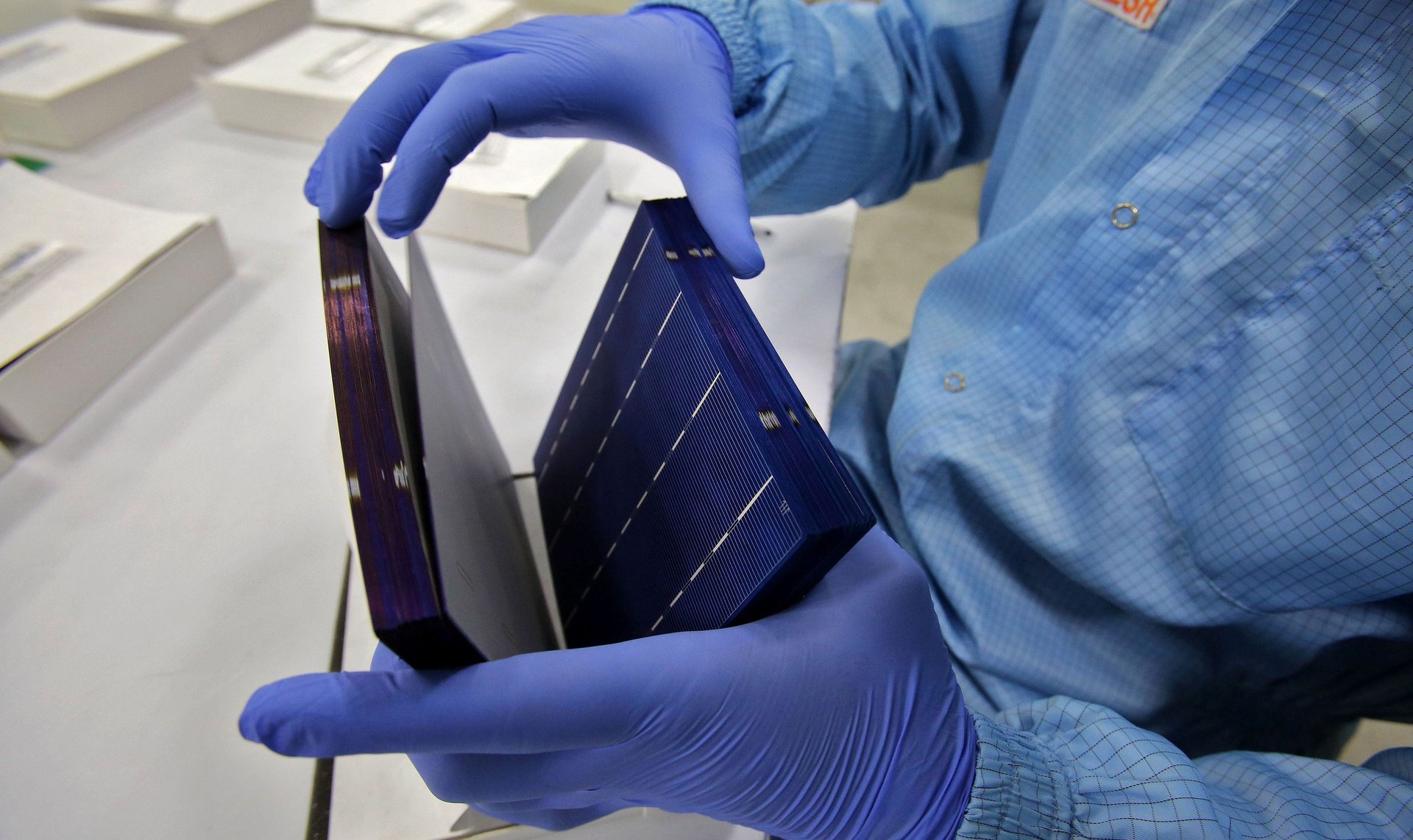

The Indian government is staunchly pursuing its plan to help domestic manufacturers challenge the dominance of Chinese solar cells and panels in the country.

The Indian government is staunchly pursuing its plan to help domestic manufacturers challenge the dominance of Chinese solar cells and panels in the country.

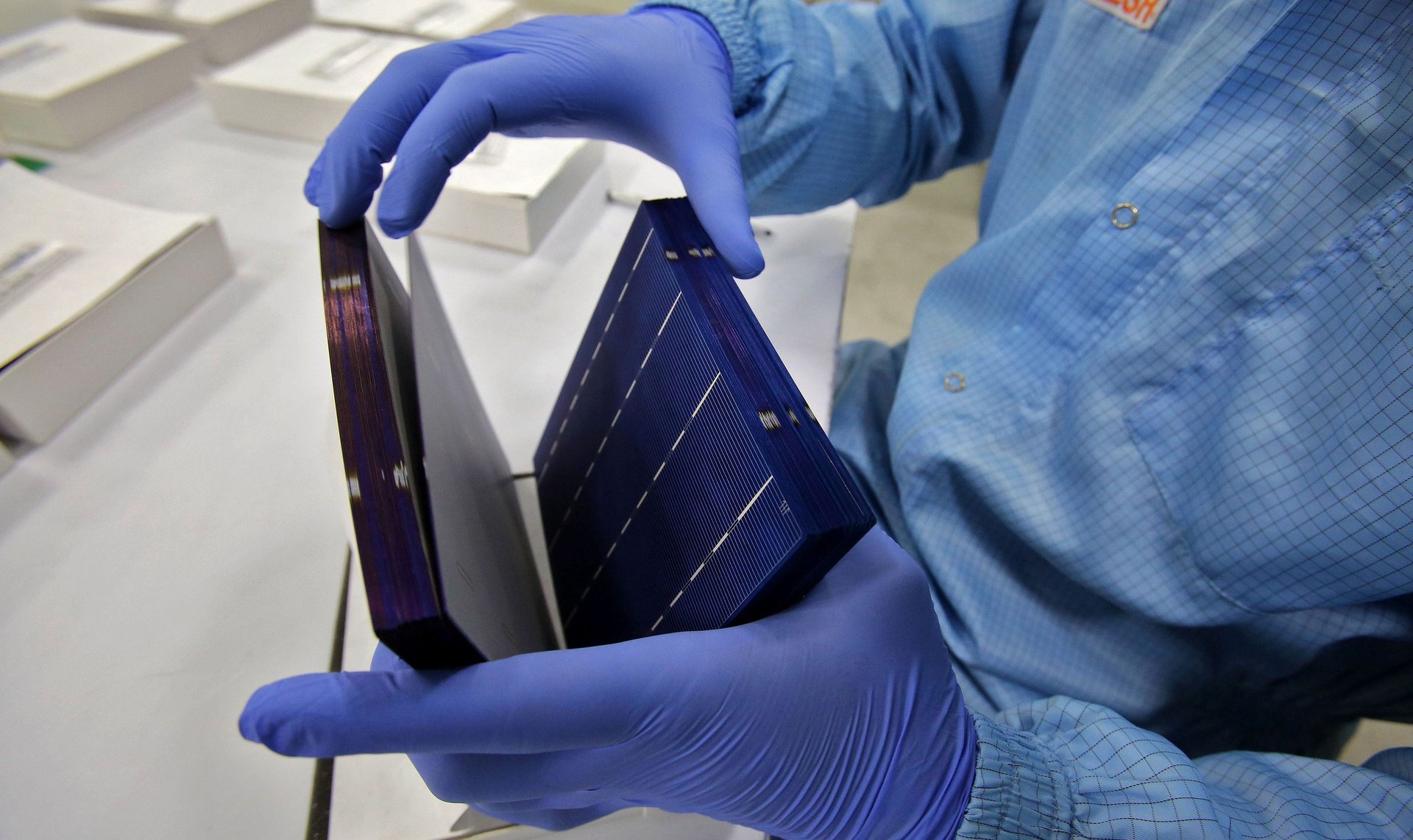

On Jan. 30, the Solar Energy Corporation of India, the government body that implements India’s solar mission, issued a tender inviting developers to build 3 gigawatts (GW) of solar power capacity. The condition: winning developers would also be required to create manufacturing facilities, which can produce 1.5 GW of solar cells and panels.

To top this up, on Feb. 05, India’s central cabinet sanctioned Rs8,580 crore for the second phase of the Central Public Sector Undertaking (CPSU) scheme, which stipulates that state-owned firms must buy 12 GW of locally-made solar panels, to generate power for their own use, over the next four years.

These recent measures come on the back of last July’s government order imposing a 25% safeguard duty for two years on imported solar cells and panels.

Yet, despite the repeated attempts, domestic manufacturers still face a formidable challenge from the established Chinese players, known for their superior quality products and economies of scale.

Note of caution

India’s ministry of new and renewable energy had proposed the second phase of the CPSU scheme in August 2017. Now that the cabinet has finally allotted funds for it, the jury is still out over how effective this will be. The details of the scheme are yet to be revealed, and domestic manufacturers are cautious.

“While on the face of it, the proposal is set to provide relief to solar domestic manufacturers for the next four years, even with immediate implementation, the on-ground reality indicates a gestation period of at least a year, till this proposal actually yields operational benefits,” Sunil Rathi, director of Mumbai-based manufacturer Waaree Energies said in a statement. “The move fails to provide the much needed immediate support to the sector, due to which, mid-scale players may not be able to sustain the pressures for the next year.”

Moreover, these measures may run foul of international trade norms.

In 2016, on a complaint from the US, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) had forbidden India from favouring local manufacturers over foreign ones while setting up solar power projects. The government, however, argues that its CPSU scheme does not violate WTO norms, which allow preferential treatment of locally-made products for self-use by government establishments.

“The question is how will the (CPSU) programme be structured so it does not violate WTO norms,” said Raj Prabhu, CEO of clean energy consultancy firm Mercom Capital Group.

For instance, take the case of the power producer National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC). Mandatory use of domestically made panels by NTPC to generate the auxiliary power which runs its coal plants may contradict the WTO ruling since the electricity generated from these plants, after all, is consumed by the public and not the government, Prabhu added.

Developer disinterest

The new manufacturing-linked tender follows the government’s failed attempts in the past to get developers to invest in manufacturing.

In May last year, the government had issued a similar tender with 10GW of solar power capacity to be added alongside a manufacturing facility of 5GW. After several extensions of deadline, the tender was finally cancelled amid tepid response from developers.

Though the new tender is less than half the size of the last one, it is also expected to fall flat, according to experts Quartz spoke with. “In the current form, without long-term clarity of viability of solar manufacturing, nobody is going to put up that much capacity,” said Amit Kumar, partner at PwC.

Though the government has allowed developers to bid for as less as one-third of the total tendered capacity, “with smaller size, you would not have the economies of scale, and you would not be able to compete with the Chinese supply,” Kumar added.

Unguarded future

The 25% safeguard duty, which has not succeeded in making Indian cells and panels cheaper than imported ones, may now get some support from the CPSU scheme and the manufacturing-linked tender, it is hoped.

A spurt in manufacturing would lead to new jobs and decreased reliance on Chinese imports, which have captured 90% of the market. Domestic manufacturers have in the past used these planks to ask for a heavier safeguard duty.

But solar developers prefer the Chinese modules for their low prices and better quality, and any effort to hurt the imports also jeopardises India’s ambitious target of more than quadrupling its solar power generation capacity to 100GW by 2022, a goal that the country may be on course to miss.