If toxic air was not enough, India’s capital city is now running out of water

As if its air was not lethal enough, New Delhi now has a severe water shortage crisis to contend with.

As if its air was not lethal enough, New Delhi now has a severe water shortage crisis to contend with.

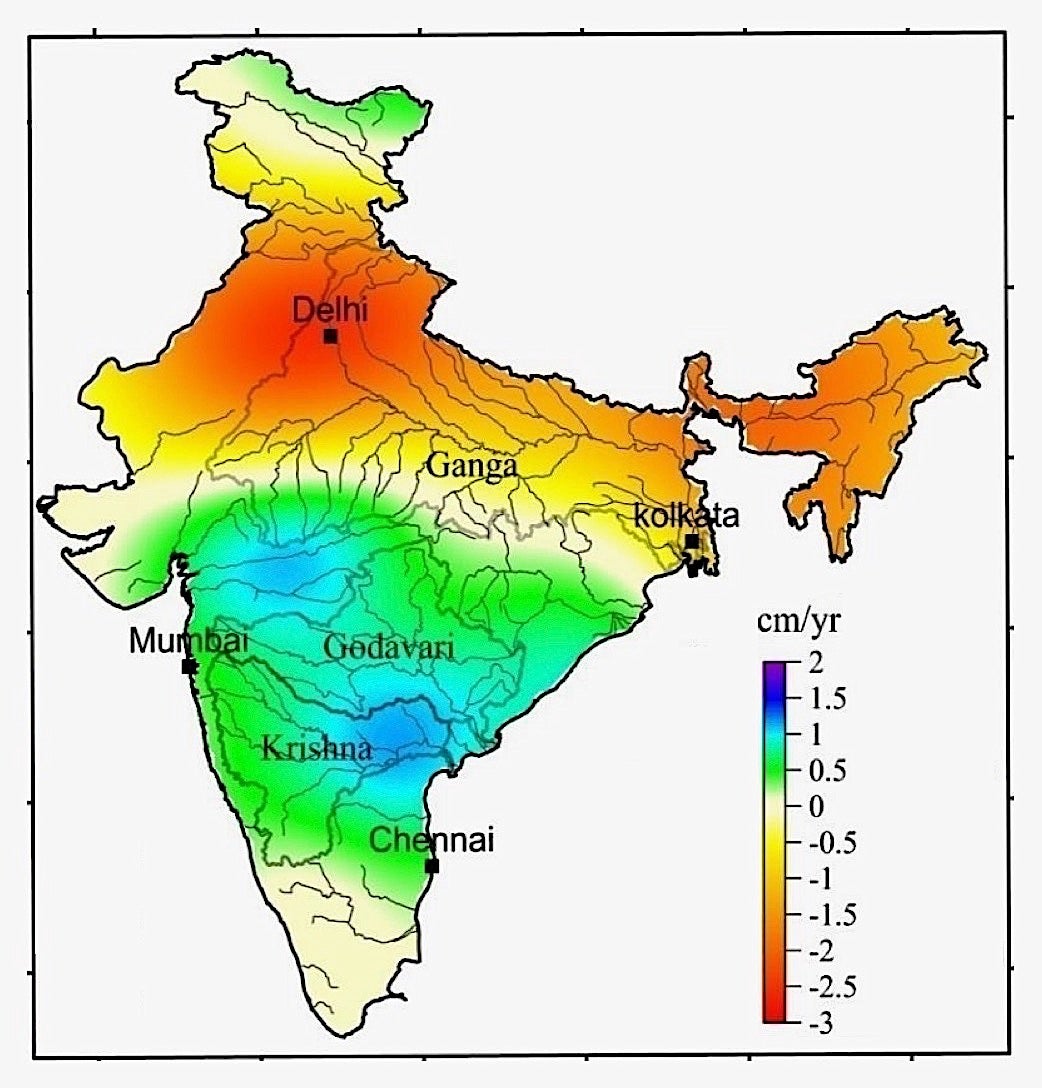

India’s capital is running out of water at the rate of over 3 centimetres of reserves from the earth’s surface and under the ground every year. “Delhi lost more than 1 metre of groundwater in the past 10 years,” said Virendra Tiwari, director of the Hyderabad-based National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI). This is faster than any other major Indian city, he said.

NGRI, a government research facility, studied the fluctuations in groundwater levels between 2002 and 2017.

In fact, the entire Indo-Gangetic plain in the north is rapidly losing groundwater. Water-intensive agricultural practices like rice cultivation have contributed majorly to thinning groundwater levels in the northern states, Tiwari said.

India’s Deccan Plateau region, on the other hand, has replenished its water resources over the years thanks to better storage of water on the surface and under the ground. Projects such as the Sardar Sarovar Dam in the western state of Gujarat, due to which larger areas get recharged after the annual monsoon, have also helped, Tiwari said.

Manifold impact

Groundwater levels in an area recede when the rains fall short of replenishing them. Areas far from the sea, such as landlocked New Delhi and other parts of north India, mainly rely on monsoons for rainfall, and any change in the annual rainfall pattern severely impacts groundwater levels.

As the levels gradually decrease, a repeat of a drought year such as 2009 threatens to run New Delhi dry, Tiwari said. Loss of groundwater also impacts soil moisture, raising air temperature, and increasing the risk of heatwaves during dry weather, he added.

Though NGRI’s research does not predict by when Delhi could run out of water, an earlier report by the government think tank, Niti Aayog, said this “day zero” could arrive as early as 2020.