India’s central bank may not have room for further rate cuts anytime soon

The Reserve Bank of India yesterday (April 04) seized its last opportunity to address growth concerns before inflationary pressures begin to reflect on the economy.

The Reserve Bank of India yesterday (April 04) seized its last opportunity to address growth concerns before inflationary pressures begin to reflect on the economy.

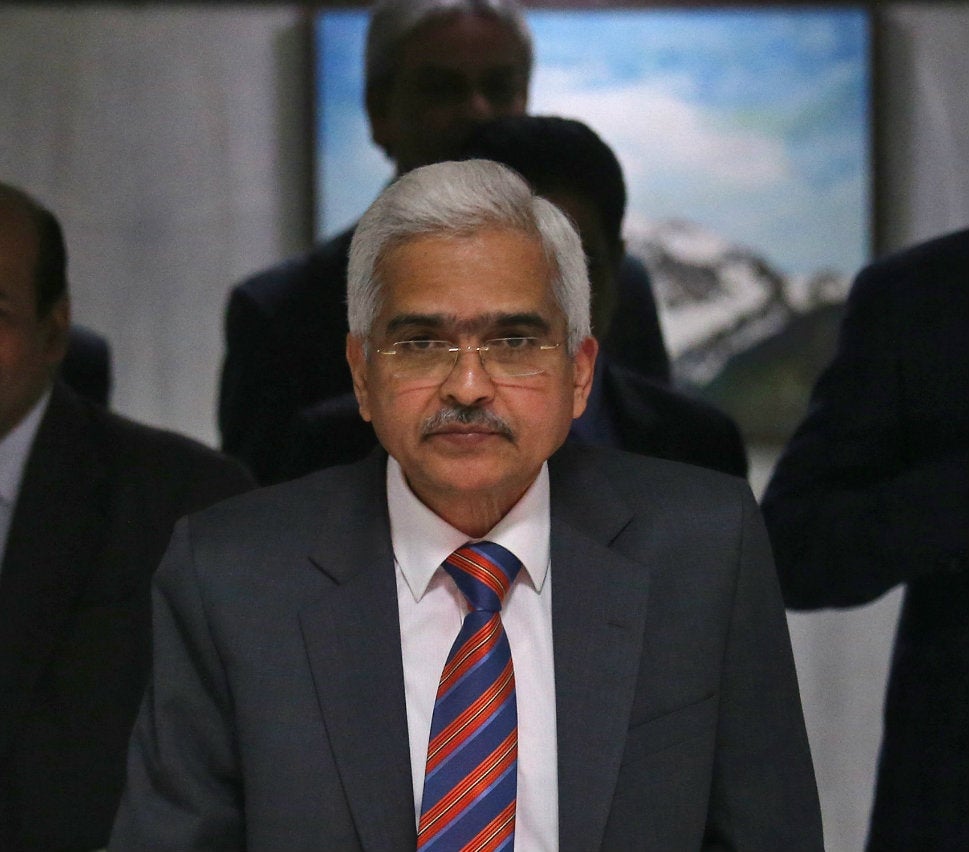

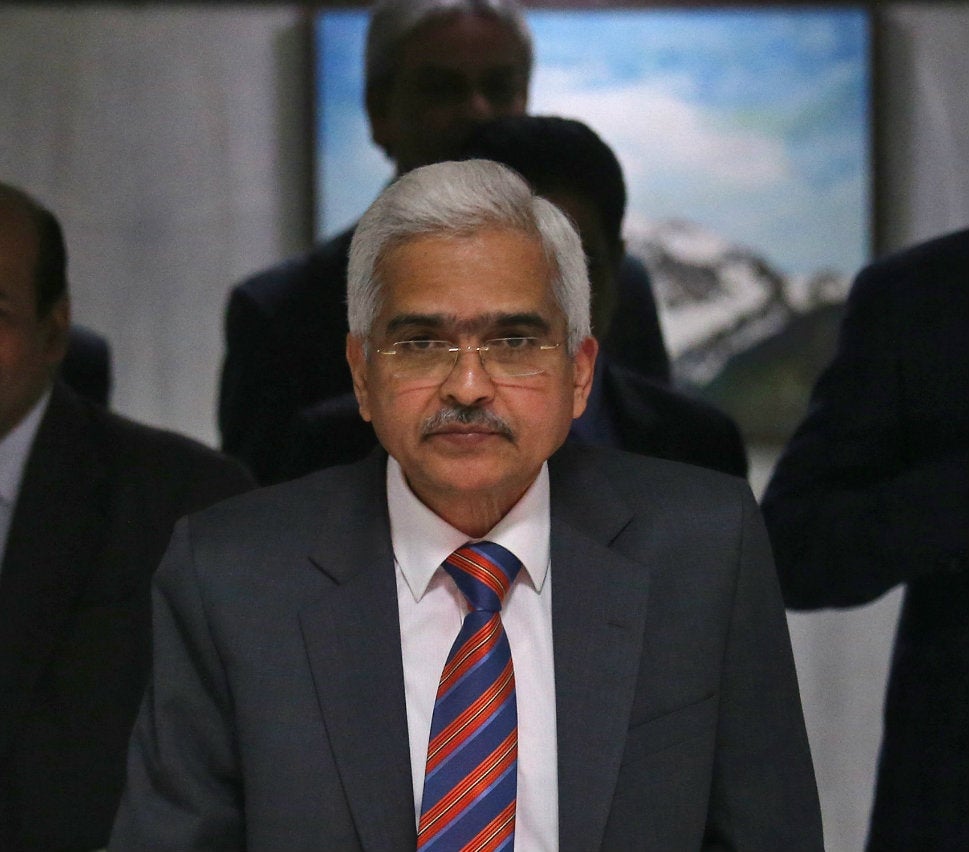

In its first monetary policy for the financial year 2020, the central bank slashed the repo rate—at which it lends to retail banks—by 25 basis points to 6%. “The domestic economy is facing headwinds, especially on the global front. The need is to strengthen domestic growth impulses,” the monetary policy statement, read out by RBI governor Shaktikanta Das, said.

What took the back seat, though, was the possibility of a build up in price pressures. Retail inflation in February this year had risen to a four-month high of 2.57%, reversing a seven-month declining trend. While this remains within the RBI’s comfort zone, the uptick is ominous.

In cutting the key interest rate, the RBI gave precedence to shoring up economic growth.

Recent macroeconomic data suggests that growth has been fizzling in the world’s fastest-growing major economy. India’s index of industrial production (IIP), a measure of manufacturing growth, expanded by just 1.7% in January, according to official data. This is a far cry from the 7.5% growth recorded a year ago.

“The growth of eight core industries remained sluggish in February. Credit flows to micro and small as well as medium industries remained tepid,” the RBI said.

Growth had a higher bearing on the monetary policy as inflation has remained within the RBI’s target of 4%, despite the uptick in February.

Uncertainties ahead

Yet medium-term inflation faces the danger of being stoked by a host of factors, ranging from global crude prices to weak monsoons. “Beyond the near term, several uncertainties cloud the inflation outlook,” the RBI said.

Consequently, the monetary policy committee (MPC), led by Das, stuck to the “neutral” stance announced in its February policy, rather than change it to “accommodative.” An accommodative monetary stance would have signalled more rate cuts in the near future.

To be sure, for the near term at least, the RBI has cut its inflation forecasts. It now expects retail inflation to be 2.9-3% in the first half of this financial year. It forecasts this to rise to 3.5-3.8% in the latter half. Though this is within the central bank’s target, the upward trajectory is notable and the predictions were made “assuming a normal monsoon in 2019.”

But this is not a given. On April 03, the private weather forecasting agency Skymet announced that it expects this year’s monsoon to be below normal, attributing it to the El Nino weather phenomenon. The monsoon season that lasts from June till September is the lifeline of Indian agriculture and any weather-related vagaries can impact food prices.

The RBI also added that there is the risk of a rise in vegetable prices, in the ongoing summer.

Oil prices

Another risk to inflation is the possibility of global crude prices flaring up. “The outlook for oil prices continues to be hazy,” RBI noted.

Oil production by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was at a four-year low in March, a Reuters survey found. Further, US sanctions on Venezuela and Iran have curtailed crude oil exports from these producers, limiting global supply and driving up prices.

Poll Overhang

There are also medium-term risks to prices if the government breaches its fiscal deficit—the difference between the government’s revenue and expenditure—targets.

Both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party and the opposition Indian National Congress have made poll promises that entail heavy government spending, to woo voters in the upcoming general election. This has left the central bank guessing. “The fiscal situation at the general government level requires careful monitoring,” the RBI said.

The possibility of these programmes fuelling inflation in the medium-term would have cast their shadow over the MPC.