The Modi versus Gandhi battle has completely eclipsed local candidates in India’s elections

Can you name the candidates contesting the parliamentary election from your constituency? It’s only reasonable if you can’t.

Can you name the candidates contesting the parliamentary election from your constituency? It’s only reasonable if you can’t.

Thanks to the media-driven fervour, the ongoing national polls in India have come to mirror a US-style presidential battle, with an intense focus on the Narendra Modi-Rahul Gandhi tussle. Lost in this narrative are the local candidates.

Twenty-four-year-old Aditya Patwari, for instance, has no idea who the candidates in his Mumbai South constituency are. When he votes on April 29, he will consider “the overall world view, and not just one policy a party has promised or executed,” he said.

Many other young people, Quartz spoke to, though, are invested and interested in local problems and would pick candidates based on their individual performance, regardless of party affiliation. Yet, attempting to dig up the past performance of candidates, they are often underwhelmed by the lack of scrutiny of local elected officials.

It is due to this information paucity that young Indians like Patwari are forced to cast their vote based on the polarised national dialogue.

Beyond NaMo vs RaGa

Among those who’d like to consider political parties’ local work is 19-year-old Dhruv Parikh. He is steering clear of the Modi versus Gandhi narrative, looking instead at his Northeast Mumbai constituency.

“They (those who vote based on party affiliations) don’t realise they are missing out on the important candidates of the area. (One should) choose an effective leader, who knows the area, and has good reforms in mind,” said Parikh. He has settled on voting for the sitting member of parliament from his constituency because “…(the candidate) has been looking after the city for years now and is aware of the demographics. He is aware of the needs and wants of the public and has made those changes.”

But most young urban Indian voters can’t access the right information on candidates and their performances. In several constituencies, the candidates are not even announced until the last moment.

Besides, in India, there is no constituency-wise break down of development metrics. “Government funds in India are allocated according to administrative boundaries of districts. But votes are asked for on electoral boundaries, which has no correlation with district boundaries,” said Yashwant Deshmukh, managing director of the New Delhi-based polling agency CVoter.

This makes it impossible to measure the on-ground accomplishments of local elected officials, Deshmukh added.

Tracking their stand on various bills in parliament is also futile as members are bound by India’s anti-defection laws to vote according to the wishes of their party’s national-level top brass.

The only limited parameter based on which voters can judge their local representatives is their diligence in parliament—attendance, number of questions posed, and whether they have spent the discretionary development funds.

Look online

In the absence of a robust official evaluation system, initiatives to raise accountability among local representatives have emerged in the country.

The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a New Delhi-based non-profit, runs myneta.info, a website that lists the official disclosures made by the candidates, such as educational background, assets, and the criminal charges and convictions against them.

Indians can now also rate their local candidates on Neta, a mobile app inspired by the US approval ratings system. Since its launch last year, the app has attracted 25 million users, founder Pratham Mittal said, noting that this is still less than 3% of India’s massive electorate: “We still have a long way to go, but at least we are moving in that direction.”

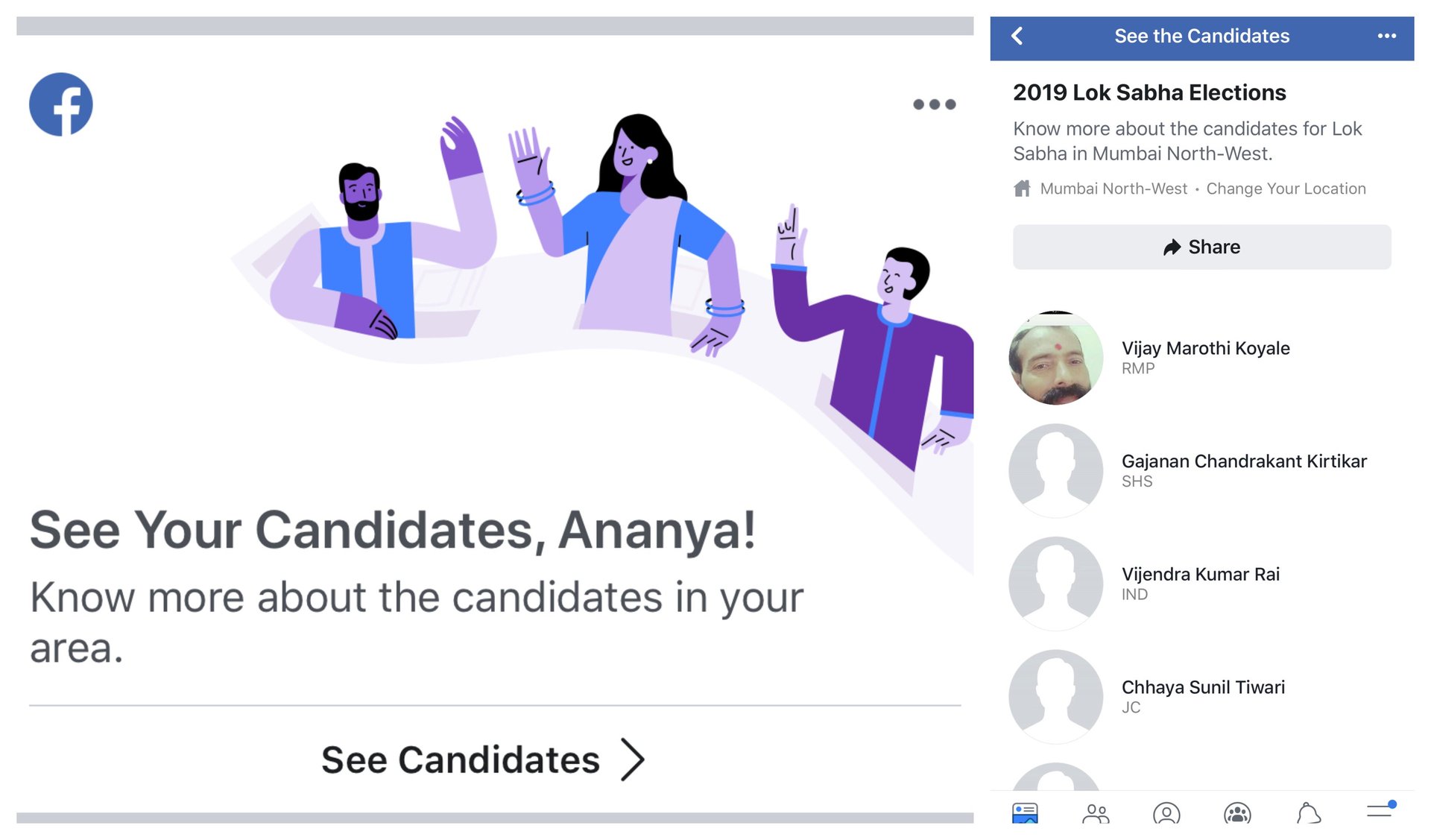

Social network Facebook, too, has launched options on its platform for India’s netizens to navigate the election at a local level. On April 11, the day of the first round of the election, the social network was prompting users to “See Candidates.” However, when you click through, the profiles of the candidates are still quite sparse, devoid of photos and extensive information.

Another Facebook tool, “Candidate Connect,” has 20-second video answers from contestants to a set of questions posed by the company. This helps voters understand their agenda better.

Yet, there still exists a dichotomy between how Indians vote and are governed, Deshmukh said. “We are a country which campaigns in a presidential system, and then votes like a parliamentary democracy.”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.