Why is Muslim political representation declining in India?

India’s Muslim population is rising. In 2015, their number stood at 195 million, which, due to high birth rates, has almost doubled since 1991, according to the Pew Research Center. Their share has increased from 12% to 15% in this time period. By 2060, Pew estimates, there will be more Muslims in India than anywhere else in the world (Indonesia has more today), and they will constitute 19% of Indians.

India’s Muslim population is rising. In 2015, their number stood at 195 million, which, due to high birth rates, has almost doubled since 1991, according to the Pew Research Center. Their share has increased from 12% to 15% in this time period. By 2060, Pew estimates, there will be more Muslims in India than anywhere else in the world (Indonesia has more today), and they will constitute 19% of Indians.

At the same time, the share of Muslims in the Lok Sabha, India’s 545-seat lower house of parliament, is in decline. Muslims have always been underrepresented here, but they are currently at a 50-year low. In the 1980 election, almost 10% of those elected were Muslim. In 2014, it was less than 4%.

The 2019 national election, the results of which will be declared on May 23, is unlikely to stop the downward trend. Researchers of Indian politics think that Hindu majoritarianism and the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the current ruling entity, is at least partly responsible for the decline, with important repercussions for Indian public policy.

Historians believe Islam first came to the Indian subcontinent in the 7th century. Over the next thousand years, Muslim rulers from central and west Asia would come to take over large parts of modern day India, promoting Islam, leading to many converts.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the British colonised the subcontinent. In the fight for independence, Muslims would be major participants (paywall). When independence was won, the colony was divided into two states, India and Pakistan. India, with a Hindu majority, but large numbers of Muslims and other religious minorities, would be a secular state. Pakistan, which then included what is now Bangladesh, would be an Islamic republic. The partition led to 15 million people moving between the countries, and over a million deaths during that migration.

About 35 million Muslims remained in India after partition. That population was and still is mostly concentrated in northern part of the country in the Ganga river basin, which includes the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal. About half of the country’s Muslims are in those three states alone. Still, nearly every part of the country has a significant Muslim minority. Of the 16 states with over 30 million people, only Odisha and Punjab are less than 5% Muslim.

The first election to the Lok Sabha happened in 1952. Of the 489 elected members, only 11 were Muslim, according to India Today. Over the next 30 years, those numbers would rise, peaking in 1980.

The increase was mostly due to great numbers within the Indian National Congress (INC), the party of Mahatma Gandhi, and the dominant political party of India after independence. Up to 30 of the 49 Muslim representatives in 1980 were members of the INC. The only other long-running parties that have consistently had more than one Muslim member are the communist parties and the Jammu & Kashmir National Conference, according to data from the Trivedi Center for Political Data.

Mohammed Osama, a political science PhD student at Jamia Millia Islamia who studies Indian politics, attributes the large representation of Muslims in 1980 to the fragmentation of Indian political parties in the late 1970s and early 1980s. With no party dominating politics, there was more of an effort to reach out to the Muslim community, and other minority groups, to cobble together a winning constituency. As a result, parties were more likely to give Muslims a chance to be their candidate.

In 1980, it would have appeared that the under-representation of Muslims—sometimes referred to as the “missing Muslims” (pdf)—was a thing of the past. Instead, the progress made by Muslim politicians was almost completely reversed in the next three decades.

Research by political scientists Christophe Jaffrelot and Gilles Verniers, who have studied this matter, points to one major reason for their decline: the rise of the BJP.

Founded in 1980, the BJP first ran candidates in the 1984 national election, winning just two seats. But the party would grow quickly. By 1998, it would lead a coalition government running the country, and in 2014 it won an outright majority under the leadership of current prime minister Narendra Modi.

The BJP’s social policies are Hindu nationalist, promoting a Hindu-based cultural conservatism over westernization and secularism. Many Hindu nationalists express the idea that Muslims can never be truly Indians because, unlike Hindus, their holy sites are not in India. The BJP’s growth was catalyzed by the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, a mosque that many Hindus consider to be on Hindu holy ground, and the 2002 riots in which over 1,000 people, most of whom were Muslims, were killed in the state of Gujarat (Modi was the state’s chief minister when this violent episode occurred).

The economic ideology of the party has shifted over the years. Currently, they are a difficult-to-pin-down combination of pro-market and anti-red tape, but also populist when it comes to policies to support India’s large number of agriculture-dependent poor.

Unsurprisingly, the BJP has had few Muslim candidates. Jaffrelot and Verniers point out that, since 1980, the party has put up only 20 of them for general elections, just three of whom have won. Of the party’s 282 current Lok Sabha members, none is a Muslim—the first time in the history of independent India that a winning party has had no Muslim members.

Nearly all of the decline in Muslim representation has come from fewer members from the states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and most importantly Uttar Pradesh. The BJP has recently grown more powerful in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state and a bellwether (paywall) for its national elections. In concert, the number of Muslim members of parliament from here fell from 18 all the way down to 0 in 2014, when the BJP won 71 out of the 80 seats allotted to the state. Around 20% of Uttar Pradesh’s population is Muslim.

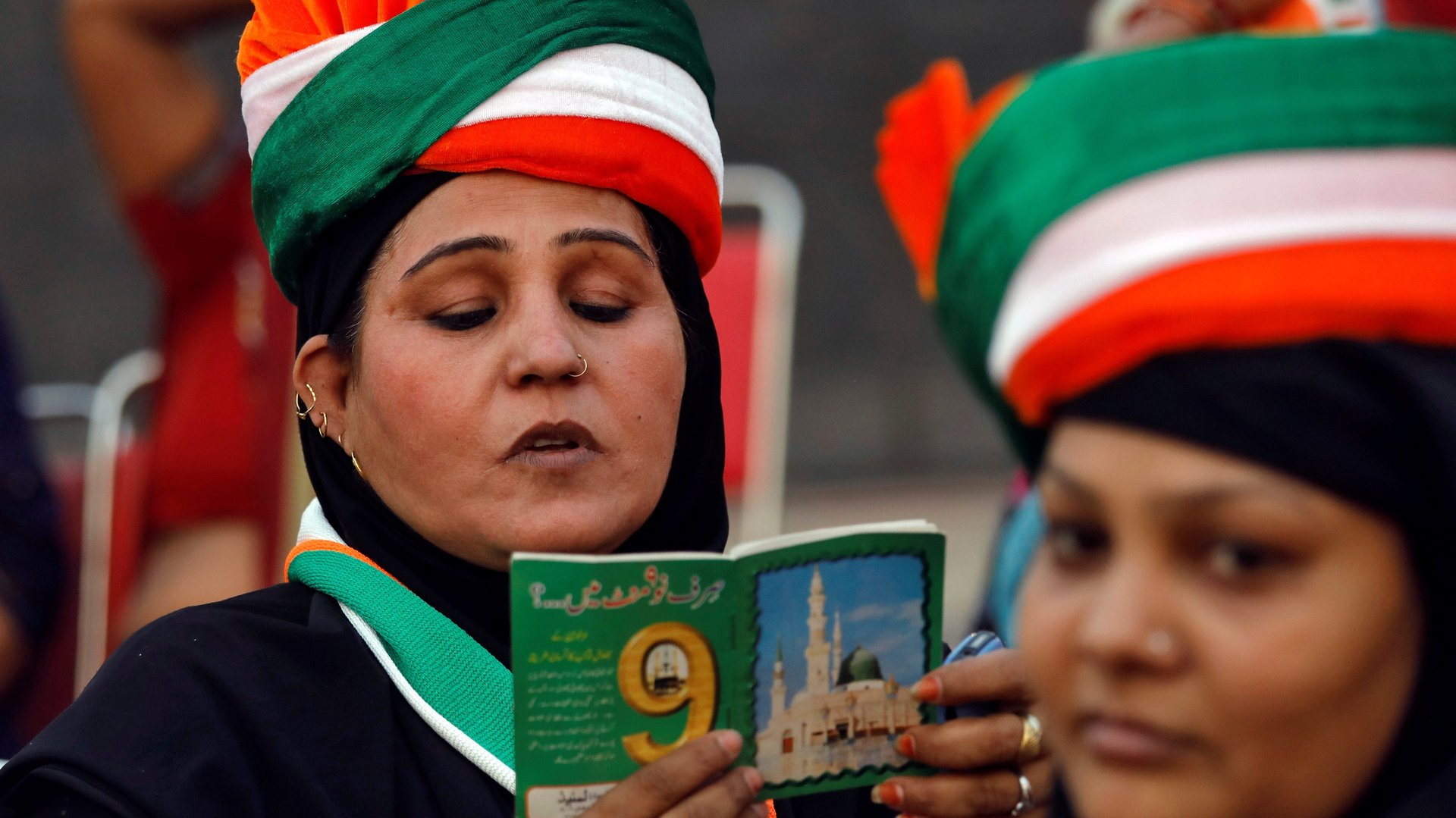

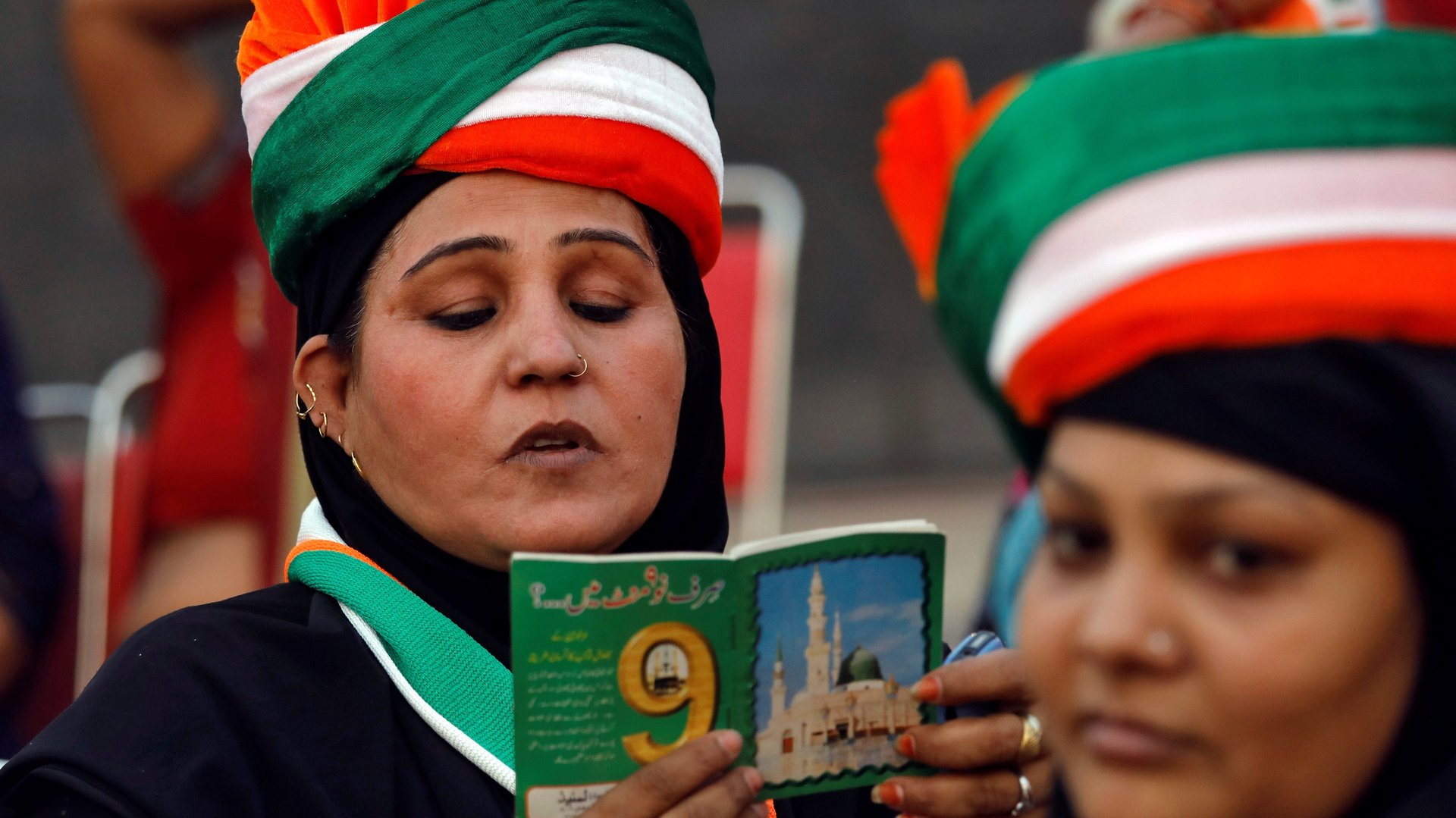

Since 2014, many Muslims have expressed concerns that the BJP is further marginalizing them (paywall), and that the government does not speak out against expressions of anti-Muslim bigotry. Human Rights Watch finds a rising number of attacks against Muslims accused of eating or killing cows—considered sacred by many Hindus. Some Indian Muslims report fears of wearing clothing that identifies them as Muslim.

Verniers believes anti-Muslim sentiment stoked by some in the BJP has also led to fewer Muslim candidates outside the BJP (paywall). The INC and other parties fear being pegged as anti-Hindu if they promote Muslim candidates. As a result, it seems highly unlikely that the number of Muslims will increase significantly during this election, though a less dominant showing by the BJP in Uttar Pradesh could lead to at least a few more Muslim members.

The lack of Muslims in the Lok Sabha may have serious policy consequences according to the political researcher and computer scientist Saloni Bhogale. She analyzed a set of 276,000 questions asked in parliament from 1999 to 2017, and found that Muslim representatives were far more likely to ask questions about issues that particularly concerned the community, including on violence against Muslims and treatment of Muslim prisoners. Bhogale points out that the low number of Muslim women—less than 1% of Lok Sabha members are Muslim women—means the issues concerning this segment is particularly unlikely to be heard.

The 2019 election is a crucial moment for Muslims in India. Another BJP landslide, which exit polls suggest is likely, could mean a further sidelining of the country’s biggest minority.