Much of the blame for India’s massive undernourished child population rests on teenage motherhood.

India is home to more stunted children than any other nation and is one of the 10 countries with the highest rates of teenage pregnancy, according to research from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Of the 60,096 mother-child pairs from India analysed by IFPRI, 14,107 women (around 25%) first gave birth during adolescence.

The study found that stunting and underweight prevalence were over 10 percentage points higher in children born to adolescent mothers than in children born to adult mothers.

“The strongest links between adolescent pregnancy and child stunting were through the mother’s education, her socio-economic status, and her weight,” said study co-author Samuel Scott.

Compared to adult mothers, teenage mothers were shorter and more likely to be underweight and anaemic. These young girls were also less likely to access health services and had poorer complementary feeding practices. They were also grappling with lower education, less bargaining power and living in poorer households with poorer sanitation.

Solution? End early marriage

Although marriage before the age of 18 years is illegal for women in India, a sizeable share of girls are married before their 18th birthday and many of them even give birth by the age of 18, according to the 2016 National Family and Health Survey (NFHS).

This is despite the fact that 73.3% of teenage girls want to marry only after the age of 21. “Continuing schooling, exploring employment opportunities, and delaying marriage and pregnancy are challenges for India’s girls that are reinforced through patriarchy and social norms,” said IFPRI senior research fellow and the study’s co-author, Purnima Menon.

Some strategies to increase age at marriage in low- and middle-income countries include unconditional cash transfers, cash transfers conditional on school enrolment or attendance, school vouchers, life-skills curriculum and livelihood training, as per review of interventions tried and tested around the globe.

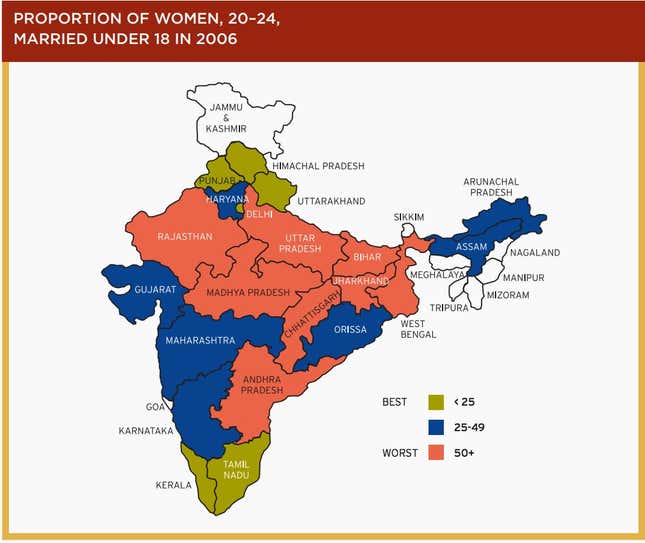

In India, the problem isn’t geographically uniform. In many northern states, a skewed sex ratio leads to a shortage of eligible brides, further fuelling the demand for underage girls.

So, both the central and state governments have tailored and piloted different cash transfers conditional on education to keep girls in school.

In Tamil Nadu, for instance, the 1992 Girl Child Protection Scheme provided for a girl child to obtain free education and a bonus of Rs1,00,000 ($1,425) on turning 18. Then, several other such schemes came up across states like Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Goa, and Gujarat.

In some cases, though, cash transfers backfired still. An evaluation of Haryana’s Apni Beti Apna Dhan (Our Daughter, Our Wealth) scheme revealed that parents were marrying their girls off just after they turned 18 to redeem the monetary reward and then use it toward marriage expenses. Many a time, the money is put towards dowry.