India’s farmers are getting desperate over a 33% shortfall in June rains

The next few weeks will be crucial for Amreesh Rathi.

The next few weeks will be crucial for Amreesh Rathi.

Monsoon evaded his Chhachhrauli village in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh throughout June. The 42-year-old farmer cannot sow the seeds of his rice crop until it rains. It is a race against time. The more he delays sowing, the smaller his harvest will be.

India gets about 70% of its annual rainfall in the monsoon season, which lasts roughly from June to September. Farmers across the country grow their most water-intensive crops during this period.

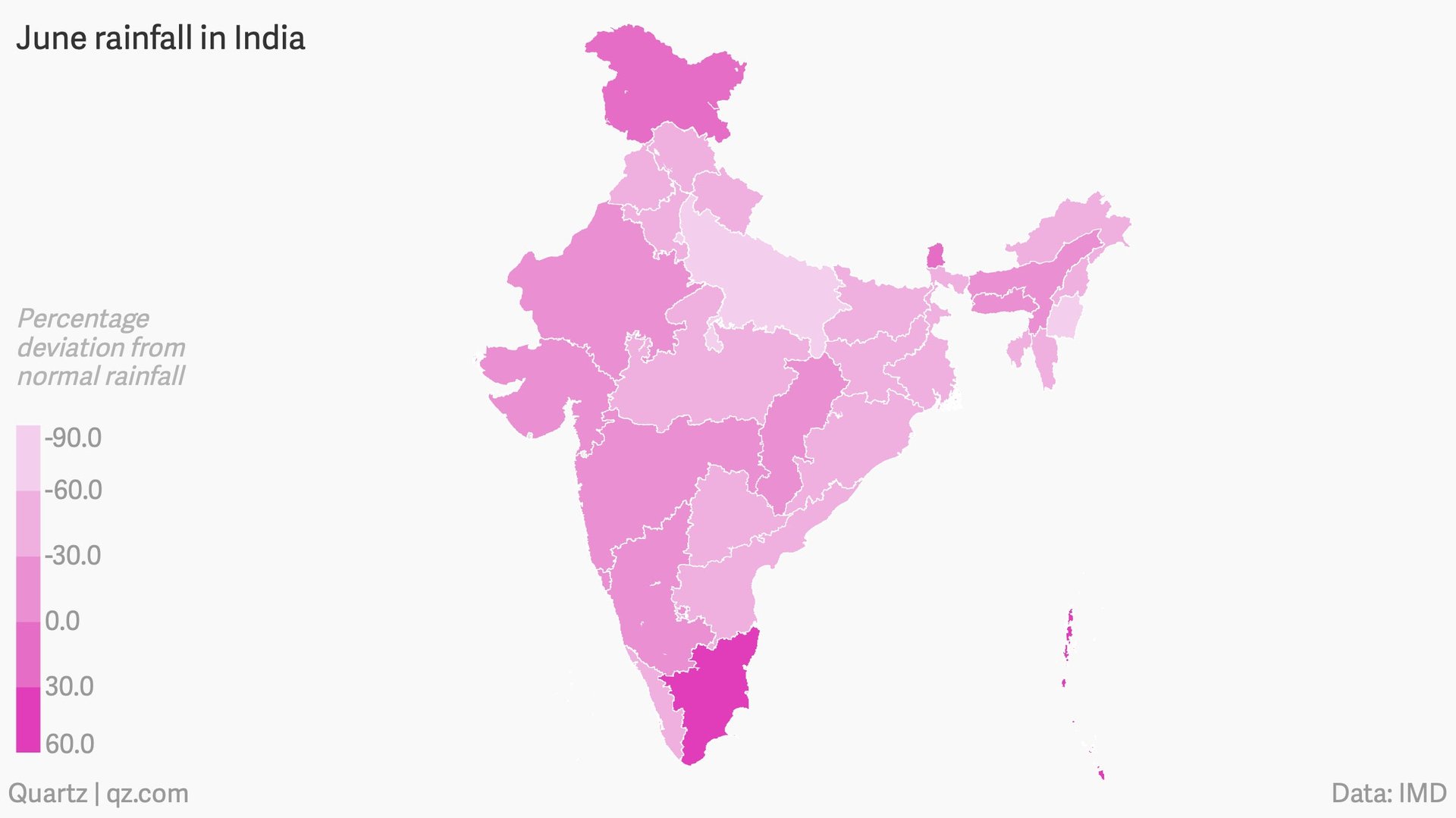

However, this year, the first month of the monsoon has ended with 33% lower rainfall than the 50-year average, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

Some parts of the country, such as rural regions of the western Maharashtra state, are reeling under drought-like conditions and a shortage of drinking water.

The total area under cultivation of summer-sown crops is down 9.5% since last year as farmers have delayed planting seeds on their fields in the anticipation of the rains. Moreover, soil moisture has been lost to the summer heat, said Vijay Sardana, a New Delhi-based agribusiness expert.

Agriculture and allied industries contribute over 17% to India’s GDP, and employ nearly 56% of its population. But farmers’ incomes have long been stagnant in what is widely acknowledged as a crisis in the country’s rural economy.

Those who can access irrigation facilities have proceeded with sowing. Relying on water from his tubewell and the Upper Ganga canal, which flows through his village of Aurangabad Fazalgarh in Uttar Pradesh, Shyambhir Singh has planted his sugarcane crop. But due to power cuts, he said, he can only run the tubewell for, at the most, seven hours a day.

Rathi, on the other hand, does not own a tubewell. Even if he rents one from a better-off farmer, it will not compensate for a deficient monsoon. “Sugarcane can be cultivated even without the rain because it needs irrigation once in 10 days. But paddy crop needs to be submerged in water through most of its life,” Rathi said.

Most of the fodder for cattle and other livestock grows naturally and is not irrigated, so insufficient rainfall lowers its quantity, too, resulting in a loss of animal productivity, Sardana said. “If rains don’t pick up, milk production, too, will be lower and calving will be delayed. Then there will be a shortage in the next season,” he said.

Three more months

Though June has been drier than usual, rainfall levels recovered around its last week, narrowing the gap between this year’s monsoon and the 50-year average.

IMD director general KJ Ramesh said the department remains confident in its original forecast that monsoon this year will be “near normal”—not less than 96% of the average.

“There is no El Nino. The Indian ocean dipole is positive. We don’t see any detriment,” he said.

There is hope for a turnaround still, agreed Pramod Kumar Joshi, a veteran fellow at the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences: “If the rainfall is evenly distributed over the next three months, lesser overall monsoon may not impact the crops as much.”