There are celebrations in many quarters that the revocation of Article 370 represents a strategic master stroke, one that opens the way for India to crush Kashmiri separatism and defeat Pakistan. Unfortunately, by undoing the constitution and decades of carefully crafted policy, the current government has closed off bilateral dialogue, and encouraged the internationalisation of Kashmir.

The escalation of these conflicts will bring great costs, including the loss of India’s carefully managed reputation as a liberal democracy and a responsible nuclear power. As long as India allows its decisions to be guided by domestic populist politics instead of rigorous strategic thinking, a relatively sober Pakistan Army will benefit while an intoxicated India accrues losses that will eventually produce a monstrous hangover.

Pakistan and the status quo

The logic of partition is often used to explain Pakistani state behaviour, but the Pakistan Army’s defining trauma was the events of 1971: mutinies, civil war, decisive Indian victory and the country’s division. Almost immediately, they faced the question of whether what happened in East Pakistan would be repeated in the North West Frontier Province or Balochistan.

Then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi’s tough but pragmatic strategic clarity delivered the Indian Republic’s most sweeping and comprehensive victory to date. So it’s worth thinking about why someone so unsentimental immediately sought peace with Pakistan via the 1972 Simla Agreement, and why she avoided any radical change in Kashmir’s status even after the emergence of separatist terrorism.

The foremost reason was to avoid further internationalising Kashmir. India had bad memories of Anglo-American involvement in the late 1940s and early 1960s that strengthened Pakistan’s hand. Soviet mediation at the end of the 1965 war had not been popular in either India or Pakistan, and the Soviets were poised to insert themselves even deeper into South Asian affairs at the end of the 1971 war to the detriment of both countries.

Secondly, the potential for Indo-Pakistani reconciliation and normalisation embodied in the 1972 Simla Agreement served the two countries by placing limits on the escalation of the conflict. This exclusive escalation ladder allowed both states to maintain control of their own respective agendas. In its most pessimistic phases, the Pakistan Army’s support to separatists and jihadis was intended to tie down Indian military resources that would otherwise be used against Pakistan to repeat 1971.

At its most diplomatically optimistic, the Pakistani establishment saw the Kashmiri struggle as a card that could bring India to the negotiating table on an equal footing. The post Cold-War fantasy of dispatching India to the scrapheap of history to join the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and communist Afghanistan died in the near-war confrontations after 9/11 and the parliament attack. Through all of this, Simla played a key role in keeping the Pakistan Army interested in talking to India even at the moments of greatest tension and irrationality.

The Modi government has made it clear once it came to power in 2014 that it intended to scrap this status quo and punish Pakistan and its allies until they gave up. In many quarters of the Sangh Parivar the call was to go even further. The Pakistani assumption was that Modi was only playing to the gallery, and would eventually take the pragmatic route, just like all previous Indian governments. With this most recent shocker, it’s becoming clear that the Modi government will remain in permanent campaign mode. That means playing the nationalist, militarist, and Hindutva cards in order to retain the domestic political initiative, especially in the face of slowing economic growth.

As a result, Pakistani is now coming to grips with the fact that the India it knew is gone, and that the new establishment feels compelled to act in line with its Akhand Bharat rhetoric. What does it mean for Pakistan if the Indian government is not only uninterested in dialogue, but actually aiming to carry out the Sangh Parivar’s call to retake the remainder of Kashmir and detach Balochistan?

The limits of force

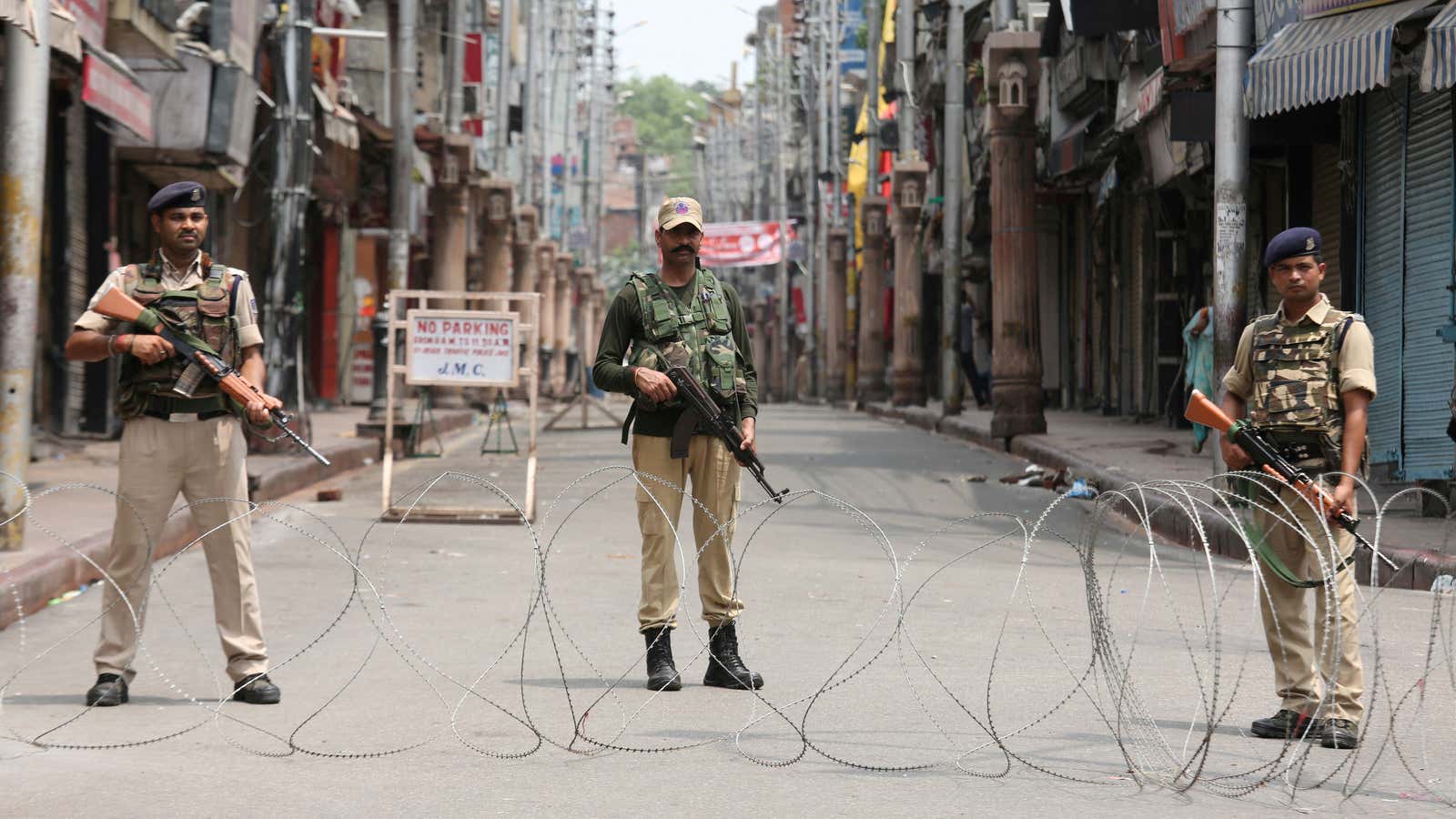

Reports indicate that the Indian government informed the United States well in advance of its status change, and hopes that American silence on the issue means that the international community will also remain silent. Israel’s success in normalising its relationship with the Arab world even while continuing to annex the West Bank, and China’s mass internment of Uighurs with the support of most Muslim governments almost certainly reinforces the views of Indian nationalists who believe that tight media controls, demographic engineering and harsh punishment will fix the Kashmiri problem. This is almost certainly mistaken. India is not Israel, nor is it China. It cannot embrace the illegal methods used in the West Bank, Tibet and Xinjiang without damaging itself in unpredictable ways.

These two countries have only able to contain the risks by engaging their neighbours, and even so, have severely damaged their global reputations. Israel’s success in crushing the Palestinians has relied on three things; the overwhelming support of the US political system, the military weakness of most Arab states, and the emergence of common threats against Israel and the Arabs. The result was peace with Egypt and Jordan, and strategic cooperation with Saudi and the UAE.

None of these things apply in the India-Pakistan scenario. The success of the Sangh Parivar in dominating BJP policy ensures that Pakistan has no reason to hope for any kind of detente or alliance with India. Nor does this aggressive approach change the fundamental balance of forces. Even in 1971, when India’s advantage was at its greatest, West Pakistan was a tough nut to crack, and the aerial skirmishes during the Balakot crisis indicate that Pakistan can still give as good as it gets.

Meanwhile, China has yet to feel secure in its Western provinces despite decades of internal colonisation efforts. Externally, China’s mistreatment of the Uighurs has gone from something they utterly denied, to a story they are now forced to actively manage. Beijing has had to invest even more deeply in its relationships with Pakistani, Turkish, and Gulf governments to the tune of billions, but there’s anecdotal evidence that its reputation is deteriorating at the grassroots level. One symptom of this is the enormous amount of security required to keep Chinese citizens safe in Pakistan, its closest ally in the world. Even in the case of India, China has had to dangle carrots such as increased trade and investment, or border dispute resolution in order to limit New Delhi’s incentives to activate the Dalai Lama and stir the pot in Tibet.

Pakistan’s opportunities

Pakistanis correctly assume that the Modi government’s systematic alienation of ordinary Kashmiris in pursuit of its right-wing populist agenda will mean more resistance in the Valley, more violence, and more risk of the government of India militarily lashing out at Pakistan. This escalation is not something that Pakistan fears. Confidence in their nuclear deterrent and conventional readiness remains high.

Diplomatically, Pakistan has always had far more of an interest in internationalising Kashmir than India; what constrained it was the Simla Agreement, India’s success at maintaining credible Kashmiri Muslim voices on its side, and the restrained use of overt military force. Modi’s government has knocked out two of those pillars, and Pakistan may be tempted to take out the third and kill the Simla agreement.

Trump has repeatedly offered to mediate in Kashmir, and the escalation of Indo-Pakistani tensions would put India in a tremendously uncomfortable position. The current US-Pakistan relationship is in some ways even better than at the heights of the Musharraf era; rather than Pakistan pretending to do what the Americans wanted in Afghanistan, Washington has come around to Pakistan’s point of view. Meanwhile the Trump Administration’s relationship with India has seen increasing friction over trade issues.

Should Trump be defeated by the Democrats in 2020, the diplomatic risks to India will likely increase. It’s unlikely that the human-rights cost of mass repression in the Kashmir Valley will be ignored. Steps like media blackouts and mass arrests of local politicians will attract rather than stifle international attention.

The current BJP treatment of minorities, intellectual dissent, parliamentary opposition and the press are all weakening India’s carefully developed reputation as a development-oriented and tolerant liberal democracy. Continued aggressive overt action across the LoC against a nuclear power like Pakistan will damage India’s reputation as a stabilising force in the region.

For those who question the impact of such reputational damage on a rising India, it’s worth thinking about the high price an over-confident Pakistani state paid when it stopped paying attention to perceptions of its behaviour. Domestic instability and criticism from the US, EU and international bodies will almost certainly generate friction that affects trade, tourism, investment, and strategic opportunities. Israel can pretend to go it alone because it has America’s unstinting support. The People’s Republic of China under Xi Jinping has taken highly aggressive positions around the world; there are serious questions as to whether its economy can sustain this approach.

All of this should encourage serious introspection on the part of Indians in government and across the nation; is the country really prepared to pick all these fights and see them through all on its own?

We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.