Every authoritarian ruler has wanted a “new” Delhi. Modi’s only the latest

Delhi is a city that has witnessed many iterations.

Delhi is a city that has witnessed many iterations.

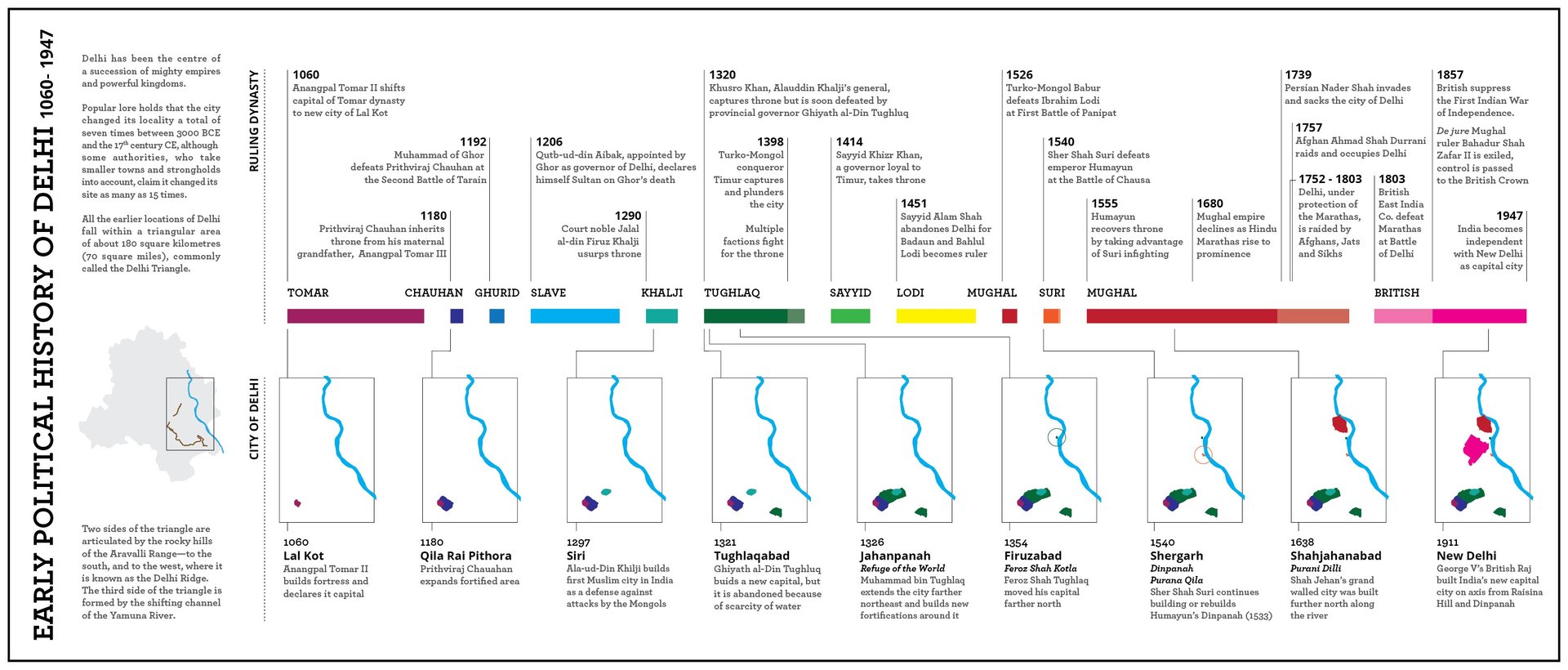

Whoever took control of the area—today a quasi state—erected new forts and constructions, practically a new city every time. The epic Mahabharata, written and compiled between 400 BCE and 400 CE, has the protagonists, Pandavas, raising their new capital, Indraprastha, in the region. In 1060, Lal Kot was founded by Anangpal in the area that is now Mehrauli. In 1300, Alauddin Khalji founded Siri. Not long after, the Turk Tughluq dynasty founded Tughluqabad, and then Jahanpanah. Firoz Shah Tughluq built Firozabad. Two centuries later, in 1538, Humayun built Dinpanah (today’s Purana Qila or Old Fort), and a century later, Shah Jahan build Shahjahanabad, in today’s Old Delhi.

The British Raj left its mark, too: Just over a century ago, Edwin Lutyens designed and built a New Delhi. It is the grand, colonial style part of today’s central Delhi that has managed to stay green, somewhat empty of people, and relatively quiet amidst the dystopia of traffic, noise, and pollution.

Now, Narendra Modi wants to leave his imprint.

The new autocrat

The Indian government plans to rebuild parts of Lutyens’s Delhi—or at the very least the Parliament House—by 2022. The prime minister, reports say, would like to redevelop the vast area between Rashtrapati Bhawan, or the presidential palace, and World War memorial, India Gate. It isn’t yet clear what the ultimate plan is, though it is said to reflect “a dream” of Modi’s, according to India’s housing and urban affairs minister.

This is likely to be a particularly symbolic change from the British Raj’s aesthetics. Many of Modi’s supporters see him as the leader freeing India from colonial hangover, dismissing foreign criticism of his government as a lingering colonial mindset.

“Authoritarians like to leave their mark on the landscape, leave things in their own image, or in the image of the values they say they represent,” Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a professor of history at New York University who focuses on authoritarians, fascism, and propaganda, told Quartz. In this sense, the desire of building a new parliament building is especially relevant. “It couldn’t be more symbolic,” says Ben-Ghiat, “and it would be very interesting, if it comes about, to see what that parliament looks like.”

Public architecture translates a certain vision of power into use of space, and Modi’s choices would reflect his. “The values of Modi would be reflected in how he does the parliament, from what he does with the design to how people are seated, and the materials to use,” says Ben-Ghiat. For instance, when the Scottish parliament was renovated, its design reflected the desire of doing away with a British hierarchical system: The building looks like it’s growing from the ground up, and everything from the seating distribution to the choices of finishing suggests transparency.

Buildings last much longer than governments, and redoing the Central Vista would leave a mark of Modi’s rule for decades to come.

A worryingly political move

There may be another reason authoritarian leaders may want to embark on big projects like these.

“One thing that unites all leaders I have studied is whenever you have large scale building projects going on in authoritarian settings, you have favoritisms, and it becomes a vehicle for patronage and corruption,” says Ben-Ghiat. “The way the authoritarian bargain works is you have to have things to give,” she says, “and building projects are a natural thing for that, too. So it’s legacy, it’s power, and it’s corruption.”

The timing is important, too. Politically, this is a tense moment for Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. The Kashmir valley has been disconnected from India for over two months, and despite the government’s claim of normalcy, reports of horrific violence and human rights abuses continue to leak out of the area.

At the same time, the government plans a bill that discriminates between refugees based on religion, restricting citizenship to non-Muslims. These are also some of the strongest actions Modi has taken since being re-elected as prime minister earlier this year.

Rebuilding New Delhi is another demonstration of the power he is projecting.

It isn’t that different in the US, where for all the promises of large infrastructure works Donald Trump made in his campaign, he seems set on one. “I consider Trump’s wall the same,” says Ben-Ghiat, “He is a builder, and his wall is his legacy.”